![]()

1

SLAVERY IN EARLY NATIONAL BALTIMORE AND RURAL MARYLAND

The story of blacks gaining freedom in Baltimore begins with the arrival of slaves from the countryside and their employment in craft work and manufacturing. Those slaves, either owned or hired from their owners, found that their masters valued and rewarded their willingness to come to the city and their productive service even to the point of granting their freedom.

Understanding how and why blacks came or were brought to Baltimore and how that process led to freedom requires an examination of the ebbs and flows of the economy and the society both in the city and in the countryside. Two rural Maryland counties, Dorchester and Prince George’s, will serve as examples of their regions. Dorchester County, on Maryland’s sandy Eastern Shore, was a rural, mixed-agriculture region in the early 1800s with a few small towns, including a modest commercial center at the county seat of Cambridge. Prince George’s County, south of Baltimore and east of Washington City, typified lower Western Shore tobacco growing counties. Almost entirely rural, its relatively richer soils allowed the profitable cultivation of tobacco long after that crop had ceased to dominate Eastern Shore agriculture. Both counties thus featured different local economies from that of Baltimore and offer different perspectives on bound labor as well. Prince George’s remained tied to tobacco and slaves throughout the early national and antebellum periods. Dorchester, like most of the Eastern Shore, shifted to a mixed-agriculture regime and gradually decreased its reliance on slavery after 1800, supplementing it with an equally mixed bag of labor forms, including tenancy, indentured servitude, labor rendered dependent by debt, and waged work.

Slaves began to live and work in Baltimore in the third quarter of the eighteenth century. It was an inconsequential hamlet before 1750, but with the opening up of the Maryland and Pennsylvania backcountry, the town grew up around mills on the Jones’ Falls Creek and the adjacent harbor, as an entrepôt for wheat, corn, and livestock. In 1768 Baltimore became the seat of Baltimore County, a thirty-mile-wide swatch of land extending from the city and the Chesapeake Bay northward to the Pennsylvania border. By 1800 rural manufacturers clustered at mills on several of the county’s smaller rivers that empty into the Chesapeake, while residents of the upper county, north and west of Baltimore city, grew grain and raised cattle in a landscape also dotted with flour mills, sawmills, and iron forges.

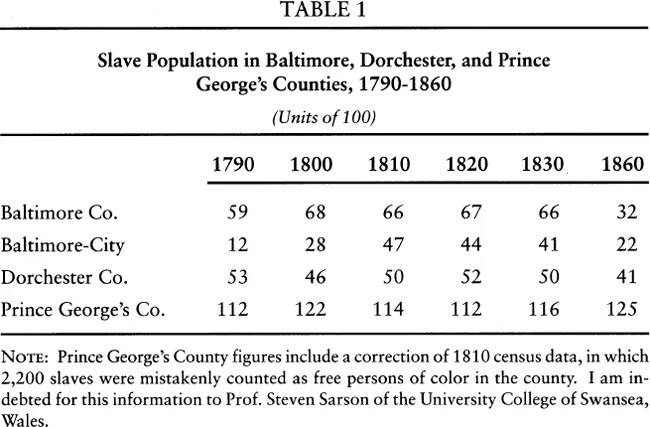

Reflecting their diverse paths of development, the three counties exhibited different histories respecting their usage of slaves (see table 1). Slavery’s growth in the city of Baltimore outpaced that of Maryland at large between 1790 and 1810, but over the next twenty years a gradual decline prevailed, accelerating after 1830. In outlying Baltimore County a modest increase in slavery before 1800 ceased thereafter.1 Likewise in Dorchester slavery dwindled rapidly after 1830, following a slow diminution that had begun as early as 1790, when the county recorded its peak slave population. Prince George’s, on the other hand, with more slaves than any other Maryland county, showed little change in slave population throughout the early national and antebellum periods. In both of the latter counties and their respective regions, masters did not welcome growth in the slave population, preferring to hire or sell off surplus “hands,” both locally and to southwestern slave traders.

Dorchester’s slight loss in slave numbers from 1790 to 1810 paralleled downturns in Eastern Shore counties such as Kent, Queen Anne’s, and Somerset. Prince George’s static demography was replicated by sister tobacco-growing counties of the Western Shore: Anne Arundel, Calvert, Charles, and Saint Mary’s Counties collectively showed a modest 5 percent increase in slaves over these decades.

Considered as a unit, Baltimore County and Baltimore city registered a 60 percent increase between 1790 and 1810, well within the range of Maryland’s fast-growing northern tier: slave population more than doubled in Washington and Allegany Counties and increased by more than 50 percent in Frederick County, about 30 percent in Harford County, and some 25 percent in Montgomery County. Growth in slaveholding accompanied the opening up of previously untilled farmlands, as slaves took on the onerous tasks of clearing land and improving farmsteads.

But slavery expanded much more vigorously in late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Baltimore city than in its outlying county or in Maryland generally: the city’s numbers nearly quadrupled, from 1,255 to 4,672, while in the rest of the county slavery increased by less than 15 percent. In fact, the city’s growth in slaveholding exceeded that of any other county in the state; at the same time the increase in outlying Baltimore County was lower than that of any other northern or western county.2

Baltimoreans purchased many slaves from rural owners. Between 1790 and 1810 city dwellers bought more than eight times as many slaves from elsewhere as they sold to owners outside the city. Better than one quarter of all sales of slaves in the county before 1810 sent a rural slave to the city.3 Slaveholders moving to town with their chattels also swelled the slave population. James Piper, a onetime Kent County planter-merchant who later operated a ropewalk in Baltimore with slave workmen, and Seth Sweetser, an Annapolitan who took his boot-making business and four slave craftsmen with him to the city, typify such migrations. Rural slave sellers, whether pressed by the debt and credit crises of the mid-1780s or by longer-term needs to reshape labor forces, supplied both new and old Baltimoreans with laborers relatively cheaply. Planters were pruning their holdings of slaves as they shifted from the year-round labor intensity of tobacco growing to crop mixes with seasonal peaks of labor demand, such as wheat, corn, and fruits and vegetables.4

City dwellers also brought slaves to Baltimore from outside the state. Although Maryland had banned importing slaves “by land or water” in 1783, Maryland residents could obtain exemptions for domestic transactions. A slaveholder had only to file a declaration identifying the slaves and specifying that their labor was intended for his use only rather than for resale. More than 300 slaves came to Baltimore in this fashion during the 1790s, mostly from Virginia, even as the practice of manumission spread.5 In 1792 the legislature authorized slaveholders fleeing Saint Domingue to bring their slaves into Maryland, a measure repealed in 1797, as fears grew that the “French negroes” would foment a slave insurrection.6 French émigrés had meanwhile declared the importation of 133 slaves. A few more slaves entered the city with masters who chose to leave New York after passage of that state’s post-nati emancipation law in 1799.7 Finally, slaveholders secured dozens of private bills from the Maryland legislature to bring in still more slaves.8

The enslaved men and women who entered Baltimore in such large numbers from the 1780s to 1820 engaged in many kinds of work, often for new masters, in both senses of the phrase: slaves dealt with owners previously unknown to them, and many of the owners had not held slaves before acquiring them in Baltimore. A look at these slaveholders, focusing on their work, their level of wealth, and the relationship between slavery and the economic environment in which these masters operated will help to sketch in more of the background to blacks’ ability to propel themselves from slavery to freedom in Baltimore.

Merchants, ship captains, public officials, and professionals such as doctors, lawyers, and bankers made up the majority of urban slaveholders, but hundreds of craft workers and manufacturers also had slaves residing in their households between 1790 and 1820.9 The breadth and depth of slaveholding in the crafts is an important element in the phenomenon of urban manumission. First, it compels caution in generalizing about artisans or mechanics as an antislavery element rendering slavery unstable in a city setting. The spread of slavery in Baltimore’s workshops from 1790 to 1810, coincident with the rise of manumission, raises questions whether connections between these two supposedly antithetical processes exist. One potential connection is that most manumissions freed African Americans only after a term of service, during which time they could be bought and sold at prices discounted below those prevailing for lifelong slaves. Purchasing such workers might have been highly appealing to craftsmen seeking to expand their command of labor as cheaply as possible.

Slaveholding in the crafts peaked around 1810, when 325 people, 19 percent of all those who could be matched from the census rolls to the city directory, held slaves. A higher proportion of practitioners held slaves in 1810 than in 1790, 1800, or 1820, in nearly two-thirds of the crafts. Most of the remaining occupations showed the broadest participation in slaveholding in 1800; only four did so in 1820 or later.10 Slaveholding thus expanded in Baltimore’s craft and industrial sector in tandem with the city’s growth until the second decade of the nineteenth century.

Both the share of all Baltimore slaveholders who worked in the crafts and the share of slaves held by artisans and manufacturers also peaked in the period from 1810 to 1820. In 1790 workers in crafts and industry made up 24 percent of slaveholders with identifiable occupations and held 23 percent of the slaves. By 1800 those proportions had increased markedly: craftsmen composed 33 percent of identifiable slaveholders and held 27 percent of the slaves. In 1810 they were 35 percent of the slaveholders and held 33 percent of the slaves. But by 1820 only 22 percent of the slaveholders practiced a craft, holding 21 percent of the slaves.11

Slaves were thus pulled into Baltimore during its rapid growth after 1780 by overlapping and mushrooming labor needs on the part of merchants, craftsmen, and manufacturers. Attracted by the ability to retain bound laborers in a boom town, even people of moderate wealth could obtain slave labor without committing themselves to lifelong ownership of slaves: throughout the period African Americans serving as term slaves pending manumission were commonly bought and sold for one-third to one-half less than slaves for life.

The rise in slavery in Baltimore’s workshops coincided with a decline in skilled work by slaves and white apprentices in the surrounding countryside. Whereas runaway ads placed by Prince George’s and Anne Arundel County masters in the Maryland Gazette described nearly a quarter of male slaves in the 1780s and 1790s as possessing artisanal skills, that proportion fell to less than one-tenth by the second decade of the nineteenth century.12 A study of Saint Mary’s County likewise found fewer skilled male slaves after 1810, a change attributable to changing market conditions: Baltimore-made goods increasingly undersold local products, reducing the utility of rural slave artisans.13 Concomitantly, many of those artisans may have been sold to Baltimore, hired their own time there, or even run away to the city, simultaneously building up Baltimore’s craft labor base and reducing the out-counties’ capacity for craft production. As for apprentices, both the volume and the proportion of rural indentures promising to train children in craft skills were lower after 1815 than previously.14

Thus Baltimore drained its hinterlands of skilled slaves, many of whom then produced manufactures in the city’s shops. The competition engendered by the distribution of those goods in rural Maryland subsequently rendered rural craft work and the associated training of slaves less profitable. Eventually, with fewer rural African Americans learning craft skills, the continued recruitment of slaves for Baltimore’s craft shops became more difficult: the scarcity of skilled slaves in rural counties after 1810 may have triggered the decline in slavery’s share of the Baltimore craft labor market.

The prevalence of manumission in Baltimore must therefore be contemplated against the backdrop of slave migration to the city. One might be tempted to think that late-eighteenth- or early-nineteenth-century manumission was a sign that supply of slaves exceeded demand, or that slavery had become unprofitable. Clearly, such a view is highly unsatisfactory, if not for rural Maryland, then certainly for the city. An alternative view, which sees gradual manumission as a tactic of employers to encourage the entry of free laborers into a labor market, also fails to account for the active recruitment of slaves for craft work. It has been suggested that white craft workers especially disliked working alongside slaves who were bound for life and that craft masters used manumission to reduce this stigma. At the same time gradual manumission would retain the services of the bound laborers until the shift to a free labor market was completed. But if the masters had had this strategy in mind, they would not have continued to purchase slaves for craft work.15

In fact, one of the prime attractions of Baltimore, for both skilled and unskilled blacks, lay precisely in its reputation as a place where a slave could gain freedom through self-purchase or delayed manumission in return for rendering highly productive labor. Thus, Baltimore’s growth, fed by voluntary and involuntary black migration, altered rural labor, choking off slavery-based craft work in the countryside. But the city could only temporarily fuel manufacturing growth with rural craft slaves; as that process shut itself down by the 1820s, new sources of labor had to be found: white immigrants and an ever-growing free black population would take the place of slaves. Nonetheless, slave-buying artisans and manufacturers played an important part in this slow transformation of Maryland’s economy and labor force.

Of course, not all the slaves in craft work were owned by those who employed them; slave hiring from merchants, rentiers, and professionals offered a short-term, if expensive, source of bound workers. Hiring or hiring out slaves was the principal means by which a slaveholder could temporarily adjust his or her supply of labor power. Of course, in this situation a slave’s willingness to work as a hireling would be worth encouraging with incentives and rewards. Shifts in the need for slave labor could arise from changes in one’s economic activities or from the evolution of one’s family structure. Advertisers seeking to hire or sell slaves routinely assured readers that they were moved not by the slave’s bad character or work habits, but by “want of employment” for the worker or by a plan to “retire from business.” Whatever the realities, advertisers clearly expected such explanations to be plausible to prospective customers familiar with Baltimore’s volatile economic climate.16

Slaves were hired, or hired themselves, for farm labor, craft or manufacturing work, and domestic service.17 Because no transfer of title to property occurred, far fewer hiring contracts survive than do records of slave sales or manumissions, making it difficult to estimate the extent of the practice. In Baltimore between 1790 and 1820, one-sixth of slave advertisements expressed a desire to hire or hire out slaves. Just under 10 percent of runaway ads noted that the fugitive had been hired out.18 Slave hiring had become common enough by the years betwee...