![]()

CHAPTER 1

WHY THIS BOOK MATTERS

Mistakes happen. When mistakes happen in medicine, the results can be deadly.

Courts have responded to the problem of medical mistakes by allowing patients to sue health care providers for medical malpractice. If a jury determines that carelessness on the part of a doctor or other health care provider caused injury to a patient, the jury can award damages—an amount of money, set by the jury, that the provider or the provider’s insurer must pay the patient. Providers do not face liability for all mistakes. Our system imposes liability only for negligent mistakes—that is, mistakes that fall below the customary standard of care that physicians and hospitals are expected to provide.

In theory, the medical malpractice liability system promotes two goals. The first is justice. Forcing negligent providers to compensate their victims—to make their victims “whole”—makes providers bear the cost of their mistakes and protects victims from having to bear those costs. The second is deterrence. Forcing providers to bear the cost of their own negligent mistakes will lead providers to devote more resources to preventing mistakes. Most providers purchase medical malpractice insurance to protect themselves from liability. Insurers may seek to reduce their exposure by researching how to provide safer, higherquality medical care and encouraging providers to adopt those practices. Insurers may also charge higher premiums or refuse to cover physicians with worse-than-expected claim rates. “Deterrence” is another way of saying that imposing liability on providers can improve the quality of medical care, thereby reducing the risk of medical injury.

In practice, the medical malpractice liability system often fails to live up to the theory. While there is evidence that the system does improve the quality of care, it could do a much better job.1 The system is slow and costly. It undercompensates some plaintiffs, especially the most severely harmed, while overcompensating others. Court decisions have both false positives (a jury finds negligence where none exists) and false negatives (a jury does not find negligence, when it in fact exists).

In this book, we examine some of the limitations of the medical malpractice liability system. We also examine the effect of tort reforms—legal reforms, promoted by physicians and insurers and adopted by many states—that limit medical malpractice liability in various ways. We assess the evidence for whether these reforms provide a cure for the limitations of the medical malpractice system that is worse than the disease—whether these reforms can frustrate the system’s ability to deliver justice and higherquality care. Our story begins with three medical malpractice “crises.”

A TALE OF THREE CRISES

Over the past 40 years, the United States experienced three major medical malpractice crises, each marked by a dramatic increase in the cost of malpractice liability insurance. The first crisis hit in the mid-1970s, the second happened in the early 1980s, and the third occurred around 1999–2005.

Each crisis fostered a vigorous debate about the causes of the premium spikes and considerable disagreement as to what, if anything, should be done about them. Physicians and plaintiffs’ lawyers were the primary adversaries in this debate, but the dispute quickly became politicized. Liability insurers and Republicans sided with physicians. Consumer groups and Democrats sided with plaintiffs’ lawyers.

Physicians and their supporters insisted that the premium spikes were attributable to problems with the legal system, including rising claim rates driven by frivolous lawsuits; rising payout per claim fostered by runaway juries; and plaintiffs’ ability to find experts who would propound junk medical science to gullible jurors. Using these arguments, physicians and their supporters proposed a variety of tort reforms, including damage caps, screening panels composed of physicians or other medical experts, higher standards of proof, and limits on contingent fees and on expert testimony—all targeting different aspects of the medical malpractice litigation process. They portrayed these reforms as crucial, lest rising malpractice premiums drive physicians away from practicing medicine; away from accepting sicker, higher-risk patients; and away from high-malpractice-risk states toward lower-risk ones.

On the other side, plaintiffs’ lawyers and their allies blamed different causes for the premium spikes. Their favorite target was insurance companies. They claimed that malpractice insurers were gouging their physician clients and that insurers contributed to premium spikes by underreserving during “soft markets.” To the extent that plaintiffs’ lawyers conceded that their activity had anything to do with malpractice premiums, they portrayed their clients as innocent victims of “bad doctors.” Plaintiffs’ lawyers argued that the proposed reforms would not prevent future premium spikes but would make it difficult or impossible for injured patients to obtain compensation. They argued that the solution to medical malpractice crises was to get rid of bad doctors and use antitrust laws to keep medical malpractice insurers from colluding with one another to raise prices.

These debates also involved larger issues of health policy. Physicians claimed that malpractice suits both drove physicians away, thus reducing patients’ access to care, and increased health care costs by causing physicians to engage in “defensive medicine.” Defensive medicine means that physicians conduct extra tests and procedures that have little or no value to patients—or that even have negative value—but that reduce the risk of a later malpractice claim. Physicians argued that adopting damage caps and other restrictions on lawsuits would attract more physicians to the cap-adopting states and reduce incentives to engage in defensive medicine, thereby reducing health care spending.

In response, plaintiffs’ lawyers argued that the evidence indicating that defensive medicine was responsible for a large fraction of health care spending was weak—and often based on self-serving statements by physicians. Plaintiffs’ lawyers also claimed that damage caps would not save money but would instead simply transfer the costs of medical injuries from providers to patients. Since most damage caps apply to noneconomic damages, the burden would fall disproportionately on patients who are less likely to be employed and thus have lower economic damages (e.g., infants, elderly patients, and women).

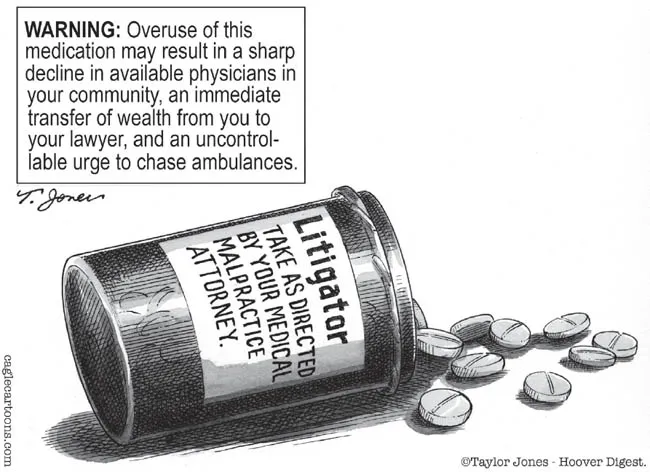

Physicians’ second argument was that premium spikes and malpractice suits reduced access to care—particularly from physicians practicing high-risk specialties, such as obstetrics and gynecology (ob-gyn) and neurosurgery, and from physicians practicing in rural areas. Figure 1.1 shows how this contention was typically framed.

Plaintiffs’ lawyers argued in response that many factors influence physicians’ decisions concerning location and choice of specialty and that liability insurance premiums were a minor factor in those decisions. They also argued that the evidence of a connection between more lawsuits and less access to medical care was weak.2

Figure 1.1

The conventional wisdom about medical malpractice (according to physicians)

Source: Medical malpractice attorneys by Taylor Jones, Hoover Digest.

Malpractice crises brought these disputes to a boil. But even when premiums are low, physicians complain that most malpractice claims are frivolous and that the litigation system is stressful, slow, expensive, and prone to error. Physicians have used the high frequency with which claims close without payment (between 75 percent and 80 percent) as evidence that most lawsuits are indeed frivolous. They argue that the defense costs associated with frivolous claims drive up the cost of malpractice coverage. They have also cast doubt on jurors’ ability to decide complex malpractice cases correctly. In physicians’ views, the cases with no payout were rightly decided, and many of those with a payout were wrongly decided, with juries prone to award huge amounts to patients who may have suffered harm, but not because of bad care.

In response, plaintiffs’ lawyers blame physicians and insurers for many of the problems with the malpractice liability system. They argue that the system is slow and expensive because physicians refuse to admit medical errors to patients and because medical malpractice insurers often litigate to the hilt even when negligence is clear. They also argue that the liability system is more often stingy than generous. Patients with valid claims are regularly sent home empty-handed, and those with severe injuries are routinely undercompensated. In the view of plaintiffs’ lawyers, the high rate at which medical malpractice claims close without payment reflects the difficulty in obtaining compensation even for strong cases, rather than the merits of the underlying claims.

Plaintiffs’ lawyers also argue that frivolous cases are uncommon. Because they are paid on contingency, plaintiffs’ lawyers assert that they cannot afford to bring weak cases and in fact reject most people who approach them seeking representation. Finally, plaintiffs’ lawyers observe that courts are the only public way to hold bad doctors accountable for the injuries they inflict. Their basic position is that the medical malpractice system may be imperfect, but it is better than the alternatives.

Many state legislatures have responded to physicians’ pleas for relief from frivolous suits with a variety of reforms. Some states took action during the first medical malpractice crisis (i.e., during the mid-1970s); others waited until the second crisis (i.e., during the 1980s) or the third crisis (i.e., 1999–2005) to do something about the problem. A few states enacted reforms during all three of the crises—while others largely did nothing. The most popular reforms, embraced by more than 30 states—including 9 during the most recent crisis—have been caps on damages.3 Most of the cap-adopting states limit non-economic damages, which are primarily intended to compensate for pain and suffering. A few limit total damages—both economic and non-economic. A fair number also limit punitive damages, but these caps are far less important in practice because punitive damages are rarely awarded and even more rarely paid. Caps vary in severity, with non-economic (non-econ) damage caps ranging from $250,000 in a number of states, including California, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, and Texas, to $1 million for death cases in Florida. Total damage caps range from $500,000 in Louisiana to $1.95 million in Virginia. Some caps are indexed for inflation, but most are not, and thus these caps become stricter over time.

The intense political debate has been marked by a shortage of evidence—as well as by a predilection for all those involved to misstate and overstate the evidence that appears to support them and to ignore contrary evidence. What effect did these reforms have? Did they make malpractice insurance cheaper by reducing the number of claims and the size of payouts? Did they improve access to health care by attracting physicians to states that adopted reforms? Did they make medical services cheaper by reducing defensive medicine? Both sides have strong opinions about these matters, but their positions are mostly talking points—often based on anecdotes rather than data.

In this book, we adopt the perspective of the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan that “everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts.”4 We have done our best to provide factual answers to these and other questions about the performance of the medical malpractice system, based on more than a decade of research. Our core findings, which we synthesize here, are based on work published in major peer-reviewed journals. These are listed in a separate section of the bibliography.

Part One focuses on Texas prior to its adoption in 2003 of a package of tort reforms—including a strict cap on non-economic damages in 2003. Part Two focuses on Texas during the post-reform period, to evaluate the impact of tort reform. Part Three evaluates nationwide malpractice trends and examines whether the Texas findings in Part Two generalize to the other eight states that enacted damage caps at around the same time. To cut to the chase, our Texas findings indeed generalize to the other states. Part Four synthesizes our findings and explores the policy implications.

Why do we devote so much effort to studying Texas? First, Texas is where the best data are—or at least were through 2012. Detailed claim-level information is crucial for analyzing many of the issues involved in assessing the effects of tort reform. Texas and Florida are the only two states that make this information publicly available. As we explain in Chapter 2, from 1988 to 2015, commercial liability insurers were required to file reports with the Texas Department of Insurance (TDI) for all claims with payments that exceeded $10,000. TDI made this information available to the public, although only through 2012. Texas’s database is better than Florida’s for the range of issues we study. For the large claims (with payouts that exceed $25,000 [1988$]) that account for 99 percent of the dollars paid to claimants, the Texas Closed Claim Database (TCCD) includes, among other things, information on claimant age, the date of injury, the dates the claim was initiated and closed, the amount paid to resolve each claim, the cost of defending each claim, the size of the applicable primary insurance policy, and whether or not the case was tried or settled. For tried cases that closed with payments, the TCCD also contains detailed information about jury verdicts and post-judgment proceedings. These rich data let us paint a detailed picture of Texas’s medical malpractice liability system in action.

A second reason to focus on Texas is that Texas adopted strict reforms in 2003, in the middle of the period for which we have data. This allows us to study Texas both before and after these reforms, and thus assess what differences the reforms made—or didn’t make. For the first decade or so covered by our dataset, Texas had a pro-plaintiff reputation, including a state constitutional right to tort damages that was guarded by a Democratic legislature and judiciary. All three branches of the state’s government became solidly Republican toward the close of the 20th century. This turnover led to greater receptiveness to tort reform and, in 2003, to an amendment to Texas’s constitution authorizing the legislature to enact a damages cap. The Texas cap on noneconomic damages, also adopted in 2003, ranges from $250,000 to $750,000, depending on the number and type of defendants.

Texas’s size also justifies a detailed examination of its medical malpractice system. Texas is the second-largest state in the United States by population, after California, and is growing fast. If Texas were a country, it would be the 45th largest by population and the 10th largest by gross domestic product.

Finally, Texas’s medical malpractice insurance crisis and the effects of the resulting damages cap have already attracted considerable attention. In 2002, the American Tort Reform Association named four Texas counties as “ju...