eBook - ePub

Théodore Rousseau and the Rise of the Modern Art Market

An Avant-Garde Landscape Painter in Nineteenth-Century France

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Théodore Rousseau and the Rise of the Modern Art Market

An Avant-Garde Landscape Painter in Nineteenth-Century France

About this book

The 19th century in France witnessed the emergence of the structures of the modern art market that remain until this day. This book examines the relationship between the avant-garde Barbizon landscape painter, Théodore Rousseau (1812-1867), and this market, exploring the constellation of patrons, art dealers and critics who surrounded the artist. It argues for the pioneering role of Rousseau, his patrons and his public in the origins of the modern art market, and, in so doing, shifts attention away from the more traditional focus on the novel careers of the Impressionists and their supporters. Drawing on extensive archival research, the book provides new insight into the role of the modern artist as professional. It provides a new understanding of the complex iconographical and formal choices within Rousseau's work, rediscovering the original radical charge that once surrounded the artist's work and led to extensive and peculiarly modern tensions with the market place.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Théodore Rousseau and the Rise of the Modern Art Market by Simon Kelly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

“The Outlaw”: Rousseau at the Salon

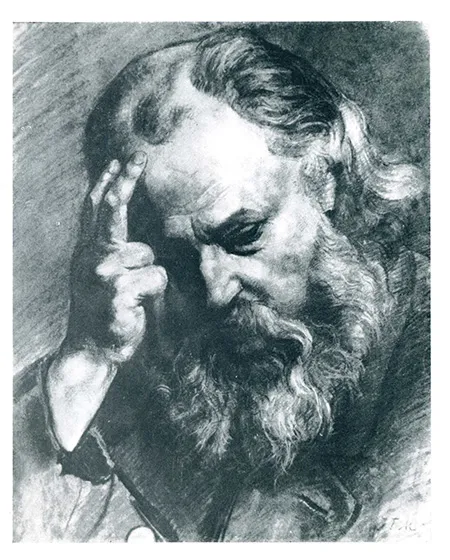

For all his involvement in novel display spaces, Théodore Rousseau was devoted to the Paris Salon. His epithet of le grand refusé, which was current by the mid-1840s, derived from the repeated refusal of his work at the official show.1 Rousseau was in fact refused on six occasions: in 1834, 1836, and from 1838 until 1841. Yet, he exhibited consistently at the Salon at the start of his career and at every exhibition, with one exception, from 1849 until his death.2 In his later years, Rousseau served on the Salon Jury and consistently sought to leverage his earlier refusals, emphasizing his sense of persecution as a means of arguing for better hanging positions or improved lighting conditions for his pictures. As Théophile Silvestre, Rousseau’s biographer, noted, he directed “vehement accusations” against the Salon jury who had refused him.3 Rousseau fashioned an identity for himself as artist outsider at a time when martyrdom was becoming a central element in an emerging modernist narrative of the modern artist.4 This persona is little evident in the existing photographs of the landscape painter but it is suggested in a portrait drawing (location unknown) by his closest artist friend, Jean-François Millet (see Figure 1.1). Rousseau, probably in his late forties, sits with head in his hands, and in deep, seemingly anguished, thought.5 The drawing speaks to the deep empathy between Rousseau and Millet.

Figure 1.1 Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, c. 1860, charcoal. Private Collection.

Many scholars, including most notably Patricia Mainardi, have documented the importance of the Paris Salon to an artist’s professional career in the mid-nineteenth century.6 Galenson and Jensen have described the arts institutional structure at this time as the “Salon system.”7 First held in 1699, the Salon expanded considerably during the early part of the nineteenth century.8 In 1812, the year of Rousseau’s birth, there were 1,298 entries to the Salon. That number had nearly tripled to 3,211 by 1831, and it reached 5,180 in 1848.9 Gustave Courbet recognized the Salon’s centrality when he wrote in 1847, “to make a name for oneself one must exhibit, and, unfortunately, that [the Paris Salon] is the only exhibition there is.”10 The Salon was a crucial shop window, offering the prospect of sale to both private patrons and the State. Around a hundred critics also reviewed the show by mid-century, providing the possibility of important publicity.11 In addition, the Salon provided awards of first-, second-, and third-class medals, which could lead to five different possible levels of the Légion d’Honneur. These could have an important market impact in legitimizing and sanctioning careers. Prizes, awards, and critical coverage offered important prestige or, in the words of Bourdieu, “cultural capital,” which was of a type different to the economic capital received in selling pictures but equally as valuable.12 Bourdieu identified three central types of capital: “economic capital,” “cultural capital,” and “social capital.” These operated in a system of mutual exchange, with the more abstract and closely related latter two types having an important impact on concrete money value, enshrined in the first type. Mid-nineteenth-century France witnessed the rise of a growing “economy of prestige.”13 An award of a Salon prize and, to an even greater degree, the Légion d’Honneur provided an institutional “alchemy of consecration.”14

Recent years have seen growing scholarship around artists’ strategies in submitting their work to the Paris Salon. Perhaps most pertinently, Petra ten-Doesschate Chu has explored Courbet’s adoption of the persona of outsider in his controversial submissions from 1844 until 1870.15 Rousseau, for his part, also emphasized his difference. He was working at a time when the genre of landscape enjoyed growing prominence. As Jon Whiteley noted, after the 1831 Salon, landscape painting “increased vastly as a percentage of the works exhibited.”16 The State also acquired increasing numbers of landscapes, to the extent that these made up approximately a third of its purchases by the mid-1860s.17 Sometimes, Rousseau aimed to make an impact with a major single picture, and sometimes with a larger body of paintings that drew attention through their cumulative force and ecological message. He highlighted the uniqueness of his output, or “brand,” with highly distinctive painting techniques that ranged from the vigorously gestural to “proto-pointillist.” At the same time, he avidly sought Salon prizes and official awards, aware of their prestige and potential market impact. Rousseau used the Salon livret as a tool in his self-fashioning, conspicuously choosing not to include the name of any teacher in his listing, as if to emphasize that he was self-taught, with only nature as a master. Only at the very end of his career, when he was seeking institutional approval, did he describe himself as a “pupil of Guillon-Lethière,” a reference to his early years in the studio of the esteemed black history painter, Guillaume Guillon-Lethière.18

Early Years

Rousseau’s commitment to the Salon was encouraged by his background. His mother, Adélaïde-Louise Colombet, came from a family of painters who had enjoyed successful, if not spectacular, careers. His maternal great uncle, Alexandre Pau de Saint-Martin (1751–1820), a pupil of the noted landscape painter Joseph Vernet, was among the first French artists to regularly exhibit views of France at the Paris Salon.19 Rousseau’s maternal uncle, Alexandre Pau de Saint Martin fils (1782–1850), was also an accomplished landscape painter, whose view of the tree-lined Champs Élysées (location unknown) won a gold medal at the 1824 Salon, and was acquired by the aristocratic patron, the Duchesse de Berry.20 Pau de Saint Martin fils provided Rousseau with his first artistic training. This family tradition was at the root of the young artist’s decision to turn to the landscape painting of France rather than the more conventionally prestigious sites of Italy, favored by academic theorists.

Rousseau made his debut at the 1831 Salon with a view of the mountainous region of Auvergne (Museum Boijmans van Beuningen Museum, Rotterdam) that he had visited the previous year. This region enjoyed a vogue among artists in the 1820s and Rousseau’s teacher, the academic landscape painter, Jean-Charles-Joseph Rémond, who had regularly painted there, probably encouraged the young artist’s visit. Critics associated Rousseau with an emergent group of young landscape painters who came to be known as the “School of 1830” and who focused on the naturalistic representation of their native France, rebelling against the Academy’s preference for historical subjects from the Bible and ancient mythology. In addition to Rousseau, the “School” included Louis Cabat, Camille Corot, Charles Delaberge, Narcisse Diaz de la Peña, Jules Dupré, Camille Flers, Paul Huet, and Eugène Isabey.21 Many of these artists, like Huet and Cabat, as well as Rousseau, held republican views, and the term reflected the closeness between the revolution that these painters brought to landscape painting and the political revolution of 1830.22

At the 1833 Salon, Rousseau submitted a view of the environs of Granville (see Figure 1.2), a coastal town in the far west of Normandy, that he had visited in 1831. He was the first to represent this town at the Salon, signaling his early interest in remote and unconventional subjects. His choice of motif was radical in its very mundanity. Rousseau paid careful attention to the rendering of tree trunks, moss on rocks, and ferns and tree foliage and largely hid a group of picturesque cottages while offering only a distant glimpse of tiny ships on the ocean. He gave prominence to his rural staffage of cart and horses, and two young children, accompanied by a goat. In an early letter, Rousseau praised peasant culture that offered a solution for “all the problems proposed by Fourrier [sic].”23 The prominent utopian thinker Charles Fourier had railed against the limitations of bourgeois materialism and sought to establish independent communities, known as “phalansteries,” that would allow the full realization of human passions. For Rousseau, the poetry and practical good sense of peasant life offered a preferable alternative to the somewhat contrived existence of the “phalanstery.” He described rural villagers as “poets in sabots,” noting that “their imaginative language is much more evocative than that of city dwellers.”24 Rousseau’s staffage in his Granville view was undoubtedly also a nod to The Haywain (National Gallery, London) by the English painter John Constable, which offered a radical model for naturalistic landscape because of its similar everyday subject and lively impasto.25 Rousseau knew Constable’s work through his friendship with the Anglo-French dealer John Arrowsmith, and probably saw The Haywain when it appeared at the Boursault collection sale in Paris in May 1832.26 For the influential critic Étienne-Jean Delécluze, Rousseau’s studied naturalism distinguished him as the leading landscape painter of the new generation.27

Figure 1.2 Théodore Rousseau, View on the Outskirts of Granville, 1833, oil on canvas, 33½ × 65 in. (85 × 165 cm). Hermitage, Saint Petersburg. Credit: State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, RussiaSputnik/Bridgeman Images.

Ro...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Plates

- List of Figures

- Series Editor’s Introduction

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 “The Outlaw”: Rousseau at the Salon

- 2 Alternative Spaces: Artists’ Societies to the Cercle de L’Union Artistique

- 3 “A Small Number of the Privileged”: The Patrons

- 4 The Art Dealers: Adolphe Beugniet to Paul Durand-Ruel

- 5 “This Dangerous Game”: The Auction Sale

- 6 The Reproduction Industry: From Etching to Photography

- Rousseau’s Legacy

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Appendix 3

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- Plates

- Imprint