eBook - ePub

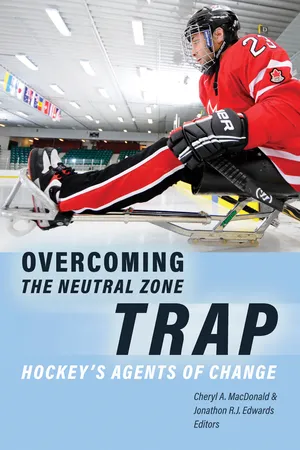

Overcoming the Neutral Zone Trap

Hockey’s Agents of Change

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Overcoming the Neutral Zone Trap

Hockey’s Agents of Change

About this book

Overcoming the Neutral Zone Trap challenges hockey's norms, pushes its boundaries, and provides new ways of conceptualizing its role in North American culture. The editors of this engaging interdisciplinary collection use the metaphor of the neutral zone trap to explore the ways that hockey's culture and structures work to exclude marginalized people. The book features both personal and scholarly accounts of agents of change—people, ideas, and events—that confront the challenges associated with making hockey a more inclusive space. By exposing assumptions about hockey culture, Overcoming the Neutral Zone Trap opens up critical discussions of previously underexplored topics as they relate to the women's game, Indigenous participation, viable career pathways, masculine identities, hockey parents, mental health, and social media. This is a book for fans, players, organizers, and researchers alike.

Contributors: Angie Abdou, Kieran Block, Cam Braes, William Bridel, Judy Davidson, Jonathon R.J. Edwards, Catherine Houston, Colin D. Howell, Chelsey H. Leahy, Roger G. LeBlanc, Cheryl A. MacDonald, Fred Mason, Brock McGillis, Vicky Paraschak, Brett Pardy, Ann Pegoraro, Kyle A. Rich, Tavis Smith, Noah Underwood

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Overcoming the Neutral Zone Trap by Cheryl A. MacDonald, Jonathon R.J. Edwards, Cheryl A. MacDonald,Jonathon R.J. Edwards in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

II

Access and Support

5

“We have to work for it. For everything. Absolutely everything.”

An Examination of the Gendered Structure of Ice Hockey in U SPORTS

CHELSEY LEAHY

SINCE THEIR INTRODUCTION TO SPORTS, girls and women have had to overcome the neutral zone trap by challenging the ideological belief of sport as a male domain (Bandy, 2016; DiCarlo, 2016). However, sport remains mainly sex-segregated and viewed as a masculine space, making it hard for some girls and women to gain the same respect and privilege as their male counterparts (Messner, 2002). The traditional emphasis on sport as a male domain has permitted the masculine institutional arrangement of sport to appear natural and unchallengeable (Messner, 2002). Giddens (1984), however, argues that individuals have the agency to create change, despite the naturalized elements of a system. The gender imbalance in sport has permitted boys and men to establish their own cultural practices, which individuals have come to understand and value as the most legitimate practices (Hall, 2002). In turn, girls and women have had to fight to gain and keep control over their own experiences, while trying to have their practices and activities viewed as legitimate by the privileged group and others (Hall, 2002).

The following chapter reports on a case study that was conducted to examine how the gendered structure of U SPORTS ice hockey impacts the experience of female players in this league. It is the result of a broader project in which the author examined the overall experiences of female varsity ice hockey players in U SPORTS from their introduction into the sport until the 2015–2016 season.

Methods

This case study used Messner’s (2002) tri-level conceptual approach to studying gender in sport, which suggests looking at gender in sport from three levels: 1) social interactions; 2) structural context; and 3) cultural symbols. This chapter specifically focuses on how players’ social interactions and the structural context of ice hockey in U SPORTS have shaped their experiences. The author took a qualitative multi-methods approach for this study to create a complete picture (Kirby, Greaves, & Reid, 2006). Kirby and colleagues (2006) argue that in social sciences there is debate “about who can be a ‘knower’ and what counts as legitimate knowledge” (pp. 63–64). For this reason, the author conducted two sets of semi-structured interviews and a document analysis.

The primary dataset was built of five semi-structured interviews with women ice hockey players who played at Rankin University (a pseudonym has been applied) during the 2015–2016 season. Participants for this dataset were deliberately selected using convenience sampling (Markula & Silk, 2011) and their status as female ice hockey players in U SPORTS playing for the same institution. Of these participants, Avery and Caroline (pseudonyms have been applied to all participants) were both in their first of five years of eligibility, while Brooke was in her second year. Dayle and Elizabeth were in their fourth years of eligibility with the intention of it being their final season, as they were expecting to graduate in the spring of 2016. Secondary datasets were used to enhance and create a more complete picture using supplementary semi-structured interviews and through information gathered from secondary sources. These secondary datasets gave the author a better understanding of the structural context of the program and U SPORTS ice hockey. The supplementary interviews were conducted with the head coach (coach) of the team and the athletic director (AD), whereas the information gathered from secondary sources was gathered from Donnelly, Norman, and Kidd’s (2013) Gender Equity in Canadian Interuniversity Sport: A Biennial Report (No. 2), as well as the “Equity Policy 80.80” of the U SPORTS Policy and Procedures, 80—Administration Manual. Additionally, secondary information was collected from Rankin University’s athletic department’s annual budget between 2011 and 2015 (received through a request for information), the regional conference’s Game Coverage and Medical Requirements document from the 2015–2016 season, and “U SPORTS Playing Regulations” for both women’s and men’s ice hockey, respectively.

The transcripts of the player interviews were coded first using open coding, which permitted the author to code using broad themes (van den Hoonaard, 2012); thirteen themes emerged at this stage. Following open coding, focused coding was used, allowing the broad themes to be placed into overarching themes within the data (van den Hoonaard, 2012). Through the focused coding, two main themes emerged: 1) common conceptions of female ice hockey players; and 2) comparison to men’s ice hockey. The latter is the focus of this chapter. Although the common conceptions of female ice hockey players are important to discuss, the players demonstrated more concern surrounding the comparison to men. For this reason, the author believes it is important to highlight the area that appeared to be shaping the majority of the experiences of these players.

Further, although the player interviews provided details about how they perceived the differences in the programs, the players spoke in broad terms about regulations and financial matters, making it unclear where exactly the differences were present, if at all. It was at this stage that the author made the decision to use a multi-methods approach to gain greater insight on the ice hockey programs at Rankin University and the structural differences between women’s and men’s ice hockey at the U SPORTS level. These secondary datasets were coded using the two themes that emerged during the player interviews.

Ice Hockey as a Gendered Space

Female ice hockey players often have stories about moments they have faced different treatment than male players. These include historically having to hide one’s female identity, such as Abby Hoffman did in 1955 when there were no girls’ teams in Toronto to play on and girls were not yet welcome to play on boys’ teams (Kidd, 2013), and Hayley Wickenheiser (2013) growing up hearing taunts from players and parents about girls not belonging in the game. Women’s ice hockey has made great strides in its ability to access the sport (Adams & Leavitt, 2018; Weaving & Roberts, 2012). However, the fight for the same, or even similar, treatment is still happening today. Take, for example, the Chatham-Kent, Ontario, female ice hockey players who were kicked out of their locker room in late 2017, when the municipality had leased the room to an all-boys AAA team, the Chatham-Kent Cyclones (Terfloth, 2017), communicating to the young girls that they were less of a priority. In turn, this shaped their experiences as female ice hockey players.

People at the centre of the gender regime of sport tend to be the ADs, players, and coaches of male high-status sports (Messner, 2011), as was the case with the AAA team in Ontario. In each of the interviews, the players focused primarily on perceived gender differences between female and male ice hockey players. Three of the five participants started by playing ice hockey on boys’ teams (or sex-integrated teams) before transferring to girls’ ice hockey around the age that body checking is introduced. Body checking was permitted at the under-thirteen age level until 2013 when Hockey Canada banned it for this age group (SportMedBC, 2017). The participants’ experiences playing youth ice hockey, in addition to how the players perceived support and resource allocation at the university level, helped to shape their experiences as ice hockey players.

Moreover, the structural difference between male and female ice hockey often influenced the players’ experiences of the game. This chapter argues that women’s university ice hockey in Canada is a gendered space (DiCarlo, 2016) based on the lack of body checking shaping women’s ice hockey, the difference in funding at the university level, and players’ (in)ability to follow their dreams in comparison to their male counterparts. In this chapter, when discussing ice hockey as a gendered space, the author is referring to how the experiences of female players are shaped based on their gender, with ice hockey being a male-dominated sport. The structural differences of the game based on gender shape the players’ understanding of their experience as female ice hockey players.

Body Checking Shaping Ice Hockey

Individuals navigate the world (and sport) within socially constructed boundaries (rules)—both formal and informal—that have been predetermined through conventional values that impact how people behave (Paraschak, 2000; Suzuki, 2017). These parameters tell players (and others) what is appropriate play and what is not. The rules of women’s and men’s ice hockey, at most levels, differ and help to shape common beliefs surrounding ice hockey (Adams & Leavitt, 2018). These beliefs shape how individuals understand the game, and which game is seen as the most legitimate (Theberge, 1998).

Although there is little difference in the playing rules, there is one major rule that can change how people understand ice hockey: body checking. Body checking refers to contact by a player on an opposing team player that has as an objective to separate the opponent from the puck (International Ice Hockey Federation [IIHF], 2018). This part of the game, which many find entertaining in men’s hockey, is prohibited in the women’s game (Adams & Leavitt, 2018). This small difference in the rules of play may be a reason behind the further regulation differences between U SPORTS men’s and women’s ice hockey. For instance, in the 2015–2016 season, U SPORTS required men’s ice hockey to have four officials on the ice. Further, the regional conference in which the institution plays requires security and an ambulance on site at every men’s game due to the perceived high risk of the sport. In contrast, the women’s game only required three officials during the 2015–2016 season, with no security or ambulance required on site. This could possibly be due to the more aggressive perception of men’s ice hockey, leading to the assumption that it is more legitimate, in comparison to women’s ice hockey (Adams & Leavitt, 2018).

Further, body checking is part of the style of play that is most often viewed as the legitimate style of play (Adams & Leavitt, 2018; Theberge, 1998, 2003). This style of play is “epitomized by the aggressive physicality of play in the [National Hockey League (NHL)], the version that really ‘counts’ in the subculture of Canadian Hockey” (Theberge, 1998, p. 186). Dayle, a fourth-year player at Rankin University, confirms this when discussing women’s hockey being perceived as inferior to the men’s game:

[In] women’s hockey there is no open ice hitting. There is bumping and stuff along the boards, but you can’t go out and make those big checks. You can’t go out hunting. You’re not going out to fight, where [in] guys’ hockey that is part of the game, [it’s] part of the excitement. That’s what the fans like…that excitement part of the game where it’s the big hits and fights. Women’s hockey it’s about puck control. It’s about running the systems. You can’t take yourself out of the play to do certain things because then they’re gone on a rush or you’re in the [penalty] box. The biggest assumption is that women’s hockey isn’t as good as men’s hockey.

Although body contact through pushing and leaning into other players, known as competitive contact, is permitted while in immediate proximity of the puck with a sole purpose of gaining procession of the puck (IIHF, 2018), the lack of body checking in women’s ice hockey is justified mostly by the naturalized size difference between women and men (Theberge, 1998; Weaving & Roberts, 2012). The naturalized difference between women and men in regard to strength and size, also known as the muscle gap (Theberge, 1998), is an ideological construct used to justify the difference in athletic performance and ability between women and men. This ideology creates a belief that women should not be playing by the same rules as men, viewing women as inferior players who are marked by a broader cultural struggle concerning gender, sport, and physicality (Adams & Leavitt, 2018). The rules of the game, regardless of the actual physicality of a game, reinforce a belief that women are weaker, and therefore should not be permitted to body check. Adams and Leavitt (2018) and Weaving and Roberts (2012) argue that this difference in rules is in place to protect female players from injury and is patriarchal in nature.

Despite women’s ice hockey having a rule against intentional body checking, which creates a game that is perceived as less physical (Weaving & Roberts, 2012), the coach of Rankin University did not believe this simple difference to be symbolic of the ability of the women to be physical, noting the fact that the men’s team had been less competitive that season:

There is nothing different between the men’s and women’s game. For a sport that has “no contact” there definitely is a lot of contact. People need to come watch it before they say, “oh it’s women’s hockey, it’s boring.” They go to the men’s games and get upset, that they are always losing. Why wouldn’t they rather come watch a game, where it is actually close, so you can get into it, and they pull out the win for you…And the game gets really physical and exciting because it’s so close and either team could win in a matter of one slip-up.

This small difference in the rules changes how fans perceive the game (Adams & Leavitt, 2018) and potentially how organizers decide what is necessary or unnecessary at arenas on game day. For instance, the requirement governing the number of mandatory officials on the ice at the time of this study was not the same, although it has since changed. The level of certification is not the same for officials refereeing the women’s games versus the men’s, which may further shape how spectators perceive the sport based on gender categories. Furthermore, the difference in the level and the number of officials required adds to the cost of running a men’s game over a women’s, and may alter how female players view financial support they receive from their institution.

Disparity in the Budget

In Canada, university student bodies consist of a majority of female students (Fletcher & Bratt, 2015). Despite this, men’s sports teams receive disproportionately more funding than women’s teams. U SPORTS has not posted the amount of Athletic Financia...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- I. Challenging Hockey’s Norms

- II. Access and Support

- III. Masculinity and Sexuality

- Afterword

- Contributors

- Other Titles from University of Alberta Press