- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

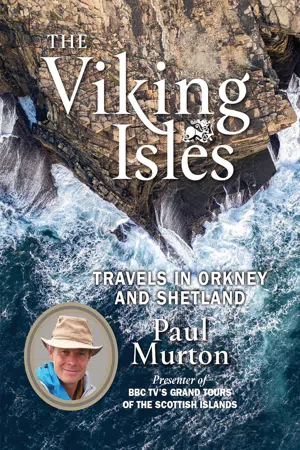

The BBC travel personality explores the Nordic legacy of these remote Scottish islands: "Engagingly written and superbly illustrated." —

Undiscovered Scotland

Paul Murton has long had a love of the Viking north—the island groups of Orkney and Shetland and the old counties of Caithness and Sutherland—which, for centuries, were part of the Nordic world as depicted in the great classic known as the Orkneyinga Saga. Today this fascinating Scandinavian legacy can be found everywhere—in physical remains, place names, local traditions and folklore, and much else.

This is a personal account of Paul Murton's travels in the Viking north. Full of observation, history, anecdote, and encounters with those who live there, it also serves as a practical guide to the many places of interest. From a sing-along with the Shanty Yell Boys to fishing off Muckle Flugga, from sword dancing with the men of Papa Stour to a Norwegian pub crawl in Lerwick, this book paints a vivid picture of these lands and their people, and explores their extraordinary rich heritage.

Paul Murton has long had a love of the Viking north—the island groups of Orkney and Shetland and the old counties of Caithness and Sutherland—which, for centuries, were part of the Nordic world as depicted in the great classic known as the Orkneyinga Saga. Today this fascinating Scandinavian legacy can be found everywhere—in physical remains, place names, local traditions and folklore, and much else.

This is a personal account of Paul Murton's travels in the Viking north. Full of observation, history, anecdote, and encounters with those who live there, it also serves as a practical guide to the many places of interest. From a sing-along with the Shanty Yell Boys to fishing off Muckle Flugga, from sword dancing with the men of Papa Stour to a Norwegian pub crawl in Lerwick, this book paints a vivid picture of these lands and their people, and explores their extraordinary rich heritage.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

Personal DevelopmentSubtopic

Travel

INTRODUCTION

Chapter opening: Eshaness.

Shetland – or the Shetland Isles – is often described as the most northerly outpost of the British Isles, a distinction which can give the impression of a bleak, subarctic remoteness. But, for the 22,500 or so people who live there, the islands are home. And, as anyone who has been there will tell you, Shetland is a well-connected place of surprising and rugged beauty, with a history to capture the imagination. True, the weather can be wild, the summers short and the winters ferocious, but there is a warmth among the people which counters even the most challenging days. And, for anyone who thinks that island people are insular, prepare to revise your preconceptions. Shetlanders are amongst the most outgoing folk in the whole of the UK, despite being branded as remote. However, geographic reality can’t be denied. Shetlanders live a long way from the rest of Scotland – and it’s further than you might think. There has been a long cartographic tradition of including the island group, along with Orkney, in a box at the top right-hand corner of the UK map. This makes Shetland look closer than it really is, which is perhaps why few people in Britain appreciate how far north Shetland is from the mainland and how its geographical position has shaped the character of both the landscape and the people.

Shetland has a history of human settlement going back at least 5,000 years. Although evidence of earlier human occupation may have been lost to rising sea levels, fine examples of Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age artefacts and structures have survived across the archipelago, which consists of 35 islands over 40 hectares and dozens of stacks and rocky skerries strung out along a deeply indented coastline of bays, known as wicks, and arms of the sea, known as voes. The most southerly point of the main island of Shetland is Sumburgh Head. From here, the nearest point on the Scottish mainland is Dunnet Head in Caithness, lying 166 kilometres across the sea to the south-east. Edinburgh is more than 450 kilometres away to the south as the crow flies. But Bergen in Norway is much closer – a mere 366 kilometres across the sea to the east. And it’s the proximity and influence of this Nordic neighbour that has helped give Shetland its unique identity. Invaders from Norway poured into Shetland from the about AD 800, obliterating the native Pictish culture. What happened to the original inhabitants is a matter of much speculation. Were they driven out of the islands completely, displaced to poorer land as some place names suggest, or were they absorbed by intermarriage with the invading Vikings, whose culture reigned supreme for six centuries? Today the Norse legacy lives on just beneath the surface and is perhaps most noticeable in Shetland place names and the dialect of the islands, which both derive from Norn – the old language of the Vikings whose deep-rooted culture has survived in various guises. Norn was still spoken in parts of Shetland up until the 18th century and a recent genetic survey has shown that 60 per cent of Shetland men can trace their ancestry back to a western Norwegian lineage. From a personal point of view, it was this Scandinavian connection that first drew me to the islands.

Shetland has always had a place in my heart and in my imagination. My father, who lived for many years in Bergen, Norway, used to sail along the Norwegian coast for pleasure in his old wooden gaff-rigged fishing boat called Blid. During the school holidays, he would take his sons for trips to explore the myriad rocky islands close to Bergen that form a sort of marine labyrinth of narrow channels and rocky skerries covered in heather and juniper. As summer days turned slowly into the magical half-light of midsummer nights, we’d moor Blid alongside an uninhabited rocky island and clamber ashore. After making a campfire, we’d grill freshly caught mackerel and talk about seafaring and the heroic age of the Vikings. Beyond the horizon, a mere 182 nautical miles to the west, lay the Shetland Islands. For centuries, they were firmly part of the Viking world and an integral part of Norse culture. The archipelago was a hub for all the maritime traffic heading west from Norway. Longships making for the Faeroes, Iceland or Greenland sailed first to Shetland or Hjaltland as it was known to the writers of the Icelandic sagas. Vikings, sailing between Norway, its colonies in the Hebrides and around the Irish Sea, would also stop over in Shetland. The islands were at a crossroads of the western Nordic world and occupied a pivotal trading and cultural position within it. A thousand years later, as we watched the sun disappear over the northern horizon in a halo of golden light, Shetland still seemed part of that lost world, despite being annexed by the Scottish crown in 1472. This happened after the marriage of James III of Scotland and Margaret of Denmark when the islands were pawned to raise money for a dowry. Although sovereignty was lost to Scotland in the 15th century, many Norwegians continued to regard Shetland as essentially part of their world – and still do. As a teenager sitting with my father in the half-light on our rocky skerry, this seemed entirely natural. Accordingly, we made plans to sail one year to discover the Viking connection for ourselves.

Sadly, I never made that trip with my father. But, years afterwards, just months before my father died, I eventually fulfilled my dream to follow in the wake of the Viking longships. In June 2012, I joined a Norwegian crew on board the yacht Hawthorne for the annual yacht race from Bergen to Lerwick. Over 40 yachts gathered at the entrance to Hjeltefjord or ‘Shetland’s Fjord’. A weathered lighthouse perched on the rocky summit of the surf-fringed island of Marstein served as the starting line. Leaving the Norwegian coast and heading due west, we watched a spectacular sunset as the flotilla of yachts gradually dispersed on the surface of the shimmering sea. Some 30 sleepless hours later, we caught our first glimpse of Shetland on the horizon – the great wedge-shaped cliffs of Noss, rising proudly from a churning sea of white-capped waves, just as they must have appeared to Viking navigators over a thousand years ago – and, to greet us, the unforgettable sight of a pod of killer whales. We rushed to the side of the boat to get a better view as they raced past. There were about a dozen of them, their backs breaking through the sea surge, the sound of their snorting breath mingling with the cries of gulls wheeling overhead. It was a truly primal moment that seemed to put us in direct touch with the Vikings of old. Unfortunately, we were brought back to reality with a bump – almost literally. A few moments later, Hawthorne was involved in a near collision with another yacht from Bergen. Angry words and Viking expletives were exchanged as we forced the other competitor to change course. The following morning, blearyeyed after a night of celebration, we were summoned to appear before the race committee. We were told that we’d broken the rules of the road and were disqualified – a disgraceful episode, surely? Yes. But, since we were already last in our class, this seemed, at the time, a less humiliating and more Viking-like outcome!

Shetland sunset.

CHAPTER 1

SOUTH MAINLAND AND THE SOUTHERN ISLES

Sumburgh Head, Lerwick, Scalloway, Walls, Sandness, Mousa, Noss, Bressay

The historic settlement of Jarlshof, near Sumburgh.

SUMBURGH HEAD

The biggest of the Shetland Isles is also the fifth largest of the British Isles. It has a population of nearly 19,000 and is known as Mainland, which can be confusing in conversation. When a Shetlander says he or she is going to the Mainland, they invariably mean they are travelling to the largest island in the archipelago – and not mainland Britain, which is usually referred to as either Scotland or England, as the case maybe. But Mainland has had other names. I have an old map in the house which calls the main island Zetland. In fact, Zetland was an alternative name for Shetland for many years and, until local government reorganisation in the 1970s, the island administration based in the capital Lerwick was known as Zetland Council. Apparently, the confusion is due to the written Scots version of Hjaltland – the old Viking name for the islands. The first two letters of Hjaltland sounded the same to 15th-century Scots ears as the old Scots letter yogh, which is written thus – 3. In this way, Hjaltland became Zetland and finally Zetland.

Sumburgh Head marks the most southerly point of Mainland and is often the first glimpse air passengers have of Shetland as their plane makes its final approach towards Sumburgh Airport. Sometimes this can be an alarming experience. The first time I flew into Sumburgh, the weather was appalling. The cloud base was not much higher than the cliffs and the twin-prop plane was bouncing around like a runaway tractor on a badly rutted field. Glancing out of the window, I saw Sumburgh Head Lighthouse through a squall of rain. I gave an involuntarily gasp as we banked steeply to line up on the runway. We were now clearly lower than the lighthouse and the cliffs and, for a moment, I was convinced that we were going to crash, which of course we didn’t. Bumpy landings in poor visibility are par for the course in this part of the world and Sumburgh Head is a formidable place whatever the weather.

Sumburgh Head is home to Shetland’s oldest lighthouse, which is perched 87 metres above wild seas on a narrow finger of cliff-girt land. Built to a design by Robert Stevenson, the grandfather of author Robert Louis Stevenson, it has braved the ferocious elements since 1821 and has witnessed a sad litany of shipwrecks and tragedy down the years, including the story of the Royal Victoria, which was on her way to India with a cargo of coal when she sank in a freezing storm in January 1864. Although 19 souls were saved, Captain Leslie and 13 others perished. He and five of his crew are buried in the parish church of Dunrossness. Inside the humble church, there’s a bell which was donated by the captain’s grieving parents. For many years, it hung outside the lighthouse where it served as a fog warning until a foghorn was installed in 1906.

In more recent times, Sumburgh Head bore witness to an environmental disaster when the Liberian-registered oil tanker Braer lost power and ran aground in hurricane-force winds on 5 January 1993. The ship was on its way from Norway to Canada with over 85,000 tonnes of crude oil, which poured into the sea when its tanks ruptured. According to the World Wildlife Fund, at least 1,500 seabirds and up to a quarter of the local seal population died. There were fears at the time that Braer’s spilt cargo would result in an environmental catastrophe similar to the one caused by the Exxon Valdez when she ran aground in Alaska four years earlier. When I visited Sumburgh in 2004, I spoke to an eyewitness who remembers standing on the cliffs at the height of the storm.

‘You could smell the oil before you could see it,’ he said, grimacing at the memory. ‘The stench filled the air and made you feel sick. The stormforce winds and churning seas were turning the oil into an aerosol and blowing inland. We thought it would contaminate the whole island. And the oil slick was also threatening the entire coastal ecosystem of Shetland. Braer was carrying twice as much oil as the Exxon Valdez and we feared the worst. Salmon farmers and fishermen thought their livelihoods would be destroyed for a generation.’

But, in fact, the strength of the wind and the violence of the seas were a saving grace and quickly helped to disperse the oil – a light variety of crude that was more easily broken down. As a result, there is no evidence at Sumburgh today of Shetland’s worst environmental disaster, although broken sections of the giant wreck still lie at the bottom of nearby Quendale Bay.

Thankfully, Sumburgh Head has been restored to nature. Although the lighthouse is no longer manned, it is still operated by the Northern Lighthouse Board and forms the centrepiece of a visitor centre and nature reserve. The awe-inspiring cliffs are home to thousands of breeding seabirds whose raucous numbers make it an internationally important site. The reserve, run by the RSPB, is home to one of the most accessible seabird colonies to be found anywhere in the British Isles and, in the past, I have been lucky enough to spend many hours watching the ever-changing scene from the cliffs. Perched in a sheltered nook, framed by sea pinks and high above the waves, I have been enthralled by the avian dramas unfolding hourly – gannets returning from fishing expeditions are attacked by ruthless and piratical skuas to give up their catch, guillemots encouraging their chicks to take their first plunge from high ledges into the waves below and, of course, the endlessly fascinating antics of puffins, which seem close enough to touch.

Just over a kilometre down the road from the lighthouse and overlooking the sheltered waters of Sumburgh Voe is the historically fascinating site of Jarlshof. Jarlshof might sound authentically Shetland, with echoes of a heroic Nordic past, but, in fact, it’s a fictitious name, which was made up by the great romantic writer Sir Walter Scott. In 1814, Scott joined his friend the lighthouse engineer Robert Stevenson on a voyage to survey sites for future lighthouses. Scott’s creative imagination was inspired by his experience of the Northern Isles – the drama of the scenery, residual Norse culture and tales of an 18th-century local pirate John Gow (who actually came from Orkney)....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Shetland

- Part 2: Orkney

- Further Reading

- Index

- Picture credits

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Viking Isles by Paul Murton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Travel. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.