- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The main aim of this book is to demonstrate the fundamental theory of advanced solid mechanics through simplified derivations with details illustrations to deliver the principal concepts. It covers all conceptual principals on two- and three-dimensional stresses, strains, stress-strain relations, theory of elasticity and theory of plasticity in any type of solid materials including anisotropic, orthotropic, homogenous and isotropic. Detailed explanation and clear diagrams and drawings are accompanied with the use of proper jargons and notations to present the ideas and appropriate guide the readers to explore the core of the advanced solid mechanics backed by case studies and examples. Aimed at undergraduate, senior undergraduate students in advanced solid mechanics, solid mechanics, strength of materials, civil/mechanical engineering, this book

Provides simplified explanation and detailed derivation of correlation and formula implemented in advanced solid mechanics

Covers state of two and three-dimensional stresses and strains in solid materials in various conditions

Describes principal constitutive models for various type of materials include of anisotropic, orthotropic, homogenous and isotropic materials.

Includes stress-strain relation and theory of elasticity for solid materials.

Explores inelastic behaviour of material, theory of plasticity and yielding criteria.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 | Introduction |

1.1 Matter

Any substance that has mass and volume, i.e. it occupies spaces, is matter. Matter is made up of discrete particles and can be categorised into three common states: solid, liquid and gas, based on the characteristics of its particles.

Solid is a state of matter with highest rigidity. A strong force of attraction between solid particles and the low molecular energy that restrains the particles’ movement endow solids the ability to hold on to their own shape. Inversely, a gas particle possesses high energy, while the attraction force between the particles is too weak to hold them in place.

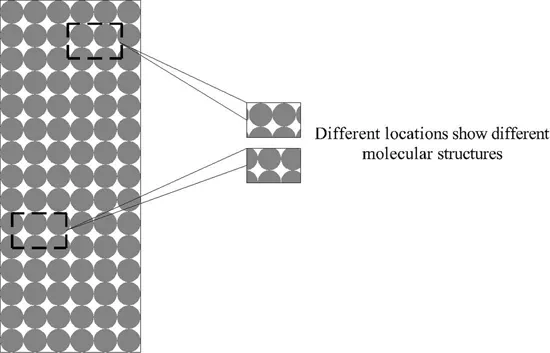

Regardless of the strength of the force of attraction, particles can never fit perfectly with one another. Gaps and discontinuities are present between particles, and, as a result, the properties of a substance vary at different locations on it at the microscopic level due to different arrangements of particles, as shown in Fig. 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Actual solid at the microscopic level.

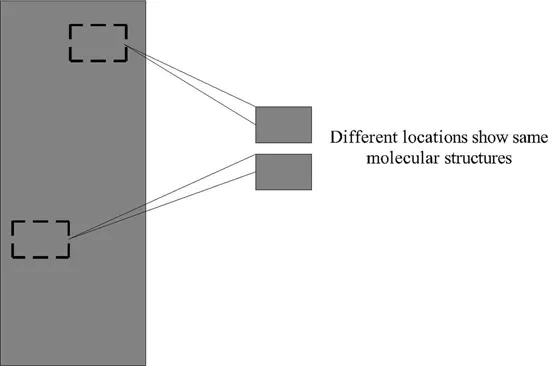

For engineering purposes, however, the microscopic discontinuities and resultant variations are neglected by considering the substance as a continuum. A continuum is an idealised matter the particles of which are continuously distributed and fill the entire space it occupies. Thus, in such an idealised matter, discontinuities are completely removed. This matter can be divided into infinitesimal elements, and all of them can exhibit the same properties. Under this condition, the properties of the matter are expressed as a continuous function of space and time. This is demonstrated in Fig. 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Continuum at the microscopic level.

A matter can be categorised into fluid or solid. A fluid is a substance that will deform continually when shear stress is applied on it. In other words, a fluid does not have shear resistance. By this definition, liquid and gas are both categorised as fluids. By contrast, solids can resist shear with their attraction force and hence do not deform continually when subjected to shear stress.

The study of a solid’s behaviour, e.g. deformation and stress distribution in both linear and non-linear manner under external forces, is known as solid mechanics, and such a study for fluids is known as fluid mechanics. Both studies are grouped as continuum mechanics, since the subject of study, i.e. the substance, is always considered a continuum.

1.2 Location as a factor affecting material properties

By assuming a material as continuum, the variation in properties at different locations on the material is solely dependent on its uniformity. The uniformity of a material is defined by the consistency in term of its composition at any point.

1.2.1 Heterogeneous Material

A heterogeneous material shows a distinctive composition at the microscopic level, at any location on it. Since all constituent materials are not evenly distributed over the material, its properties are said to be dependent on the location on the material.

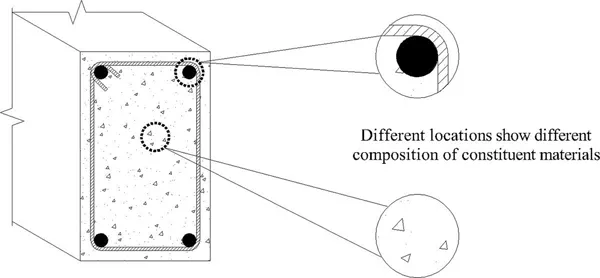

An example for heterogeneous material is reinforced concrete, which is a composite consisting of two main construction materials: concrete and steel. The dominant constituent material, concrete, shows good compression but poor tension. On the other hand, steel shows good tension, but its strength declines tremendously after being subjected to very high temperature and corrosion.

The combination of concrete and steel, i.e. reinforced concrete, is an economical solution to improving the structural member’s resistance to compression, tension, bending and shear.

For example, when load is applied on the top of a beam, a sagging moment is induced. The top of the beam is subjected to compression, while the bottom is subjected to tension. The primary reinforcing steel bars are placed at the bottom of the beam to help resist the tension. Concrete is casted around the steel bars to hold them in place and provide protection against high temperature and corrosion.

Consider that the tension is applied at two different locations on a reinforced concrete, as shown in Fig. 1.3 below. Due to the difference in composition at different locations, the material’s behaviour varies at the point that consists of concrete only; the deformation there is significantly higher than that at the point that consists of both concrete and steel.

Figure 1.3 Reinforced concrete as a heterogeneous material.

1.2.2 Homogeneous Material

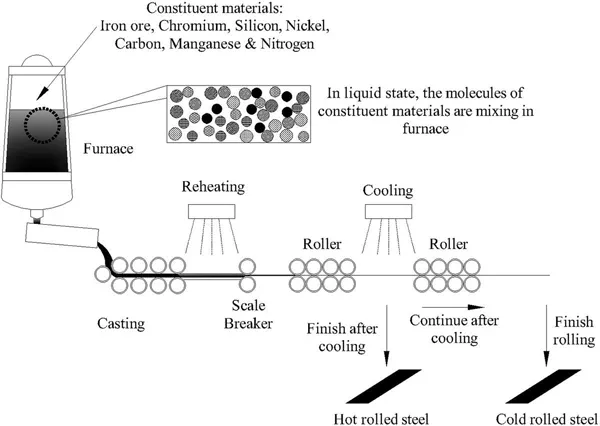

An ideal homogeneous material shows a uniform composition at the microscopic level, at any location on it. Since all constituent materials are well-distributed over the material, its properties are said to be independent of the location on the material.

An example of a homogeneous material is stainless steel. Its constituent materials are iron ore, chromium, silicon, nickel, carbon, manganese and nitrogen. The first step in manufacturing stainless steel is heating the constituent materials, melting them and letting them mix. The process is important to ensure the final product is homogeneous. Fig. 1.4 shows the steel manufacturing process as described above.

Figure 1.4 Hot-rolled and cold-rolled steel manufacturing process.

1.3 Orientation as a factor affecting material properties

A material’s behaviour also depends on its orientation with respect to the applied force. Ideally, a material is assumed isotropic to simplify engineering analysis and design. However, this is nearly impossible in the real world, as a perfect homogeneous material is impossible to be created.

Due to the imperfect uniformity in term of composition, the material will react differently to the same magnitude of force that acts along different directions.

1.3.1 Anisotropic Material

An anisotropic material shows six different mechanical properties when force is acting in six different directions along three mutually orthogonal axes, i.e. principal axes. In other words, its properties are dependent on the orientation of the material.

A composite is usually anisotropic. It is created by combining two or more constituent materials with different properties. The final material is created by arranging these constituent materials in either a specific or a vnon-specific order without breaking the arrangement of their particles. This makes the final material anisotropic, because the properties of each constituent material are only present throughout the space that such a constituent material occupies.

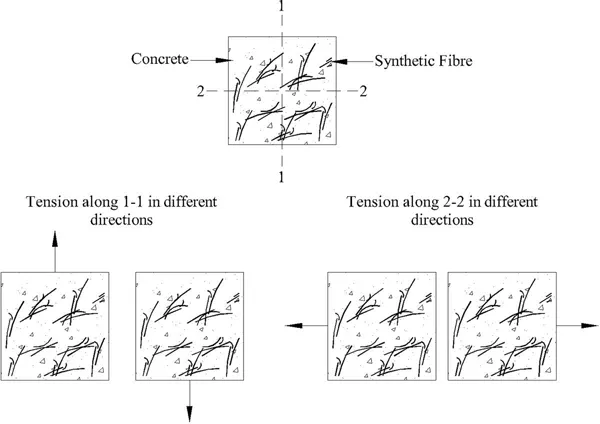

An example of a composite is fibre-reinforced concrete. In a fibre-reinforced concrete block, concrete provides principal resistance to compression, while fibre, e.g. synthetic fibre, provides principal resistance to tension. Fibre is an anisotropic material. It shows highest resistance to tension only when the force is acting along its longitudinal axis. Therefore, the orientation and arrangement of fibre directly affect the tensile strength of the concrete.

In a fibre-reinforced concrete block, the arrangement and orientation of constituent materials, aggregates, sand, cement (components of concrete) and fibres are always arbitrary in every direction. This causes the tensile strength of fibre-reinforced concrete to vary in different directions, as shown in Fig. 1.5.

Figure 1.5 Fibre-reinforced concrete as an anisotropic material.

1.3.2 Orthotropic Material

An orthotropic material shows three mechanical properties along three principal axes. Therefore, the properties are dependent on the orientation of the material.

An example for orthotropic material is timber. Timber originates from trees. The most unique characteristic of a tree is the presence of annual rings that surround its pith. For every year the tree lives, a new ring will be developed as the outermost layer of its trunk. This layer of annual rings is known as grain in timber, and it is the reason that makes timber behave as an orthotropic material.

The compressive and tensile strength of the timber varies along each principal axes of timber, i.e. radial, tangential and longitudinal are different, due to the arrangement and pattern of its grain pattern. As sh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Authors

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Stress

- Chapter 3 Strain

- Chapter 4 Stress–Strain Relationships

- Chapter 5 Solutions for Elasticity

- Chapter 6 Solutions for Plasticity

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Advanced Solid Mechanics by Farzad Hejazi,Tan Kar Chun in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Microbiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.