![]()

1

ATHENS–PORTS

Their houses still crouch about the neighbourhood—low and flat-roofed structures, some corroding and boarded up. These buildings are reconstructions, of course, the dictatorship in 1968 having forced the refugee occupants to self-demolish their original homes and rent government new builds. It was an effort to sanitise the area, though the refurbished settlements were still kept at a distance from the urban centre—or the lower-class ones were, at least. So the workers settled here, some 20 000 of them in the portside suburbs of Keratsini and Drapetsona, not venturing far from their landing point at Piraeus port. They had already come far enough, they might have figured, across the Aegean and much further. Besides, all the industry was here, in the fertiliser plant, the oil refinery, the vast dock. Greece’s prosperity was built off the back of 1922 refugee labour, I am told, including that of women and children—off the newcomers with their strange language and peasant garb, their clothing improvised from sacks and their shoes of scrap rubber. The mass arrivals at first saw municipal buildings (schools, theatres and even the Piraeus opera house) requisitioned to accommodate the displaced, mostly in the face of local opposition. And while thousands were transferred under rehabilitation schemes to purpose-built housing blocks across Greece, an informal settlement expanded here, its neighbourhoods corresponding to refugees’ departed hometowns in Asia Minor. The state allowed them—those it did not care to house or to rehabilitate—to live like this, in squats and wooden shanties, while the doctors, merchants and bureaucrats went elsewhere, inland and uphill. The area quickly became a slum. Observing the sprawl from the port, a British reverend wrote in a 1923 dispatch to London: ‘who would have foreseen that the war would tear Assyrians from their eyrie in the mountain by Nineveh and hurl them on the streets of Attica?’.

Now, the older homes are dwarfed by apartment blocks, the occasional blue and white flag draped over balcony railings. It is a Monday afternoon in winter, the weekly market is winding up and the residential streets are littered with split oranges and cardboard boxes, mannequins stacked horizontally on the roadside like the war dead. A few blocks east, the district’s main shopping boulevard has been renamed: Pavlos Fyssas street. A discreet memorial to the local antifascist rapper stands on the pavement next to a bus stop—the site where he was stabbed to death by a member of the ultra-nationalist neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party in 2013, at age thirty-four and with the silent complicity of Greek police, it is said. Fyssas’s image is carved into the granite above lyrics from one of his songs: ‘a day such as this is good to die, beautiful and standing in the public eye. My name is Pavlos Fyssas, from Piraeus’. A few offerings are laid out around the memorial—an olive sapling, some wilted carnations, a beer bottle. Down at the waterfront shipyard where Fyssas, like his father, was employed, towering cranes rise up from the dock like cathedral spires. The red and white chimney stack of the Drapetsona fertiliser plant stands disused alongside. For ninety years, the facility was the life blood of the district, churning uninterrupted through the day and night. Such was the pollution from its emissions that by Thursday each week, residents’ drying laundry was reportedly black, the sea the colour of rust. The complex then comprised 105 structures, though all but one has been torn down since 1999. The last building has been left to self-degrade, for reasons of economy. The empty entranceways and window vaults in its stone facade now gape open to the water, motionless observers to the ceaseless coming and going of freight and bodies.

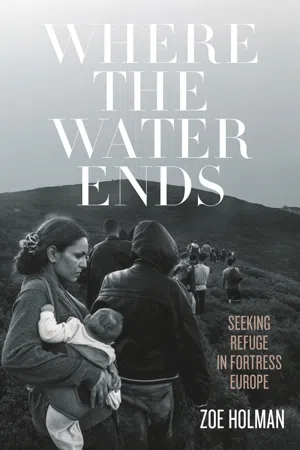

Salwa’s family didn’t stay here long. As for the some million others like them who had disembarked at Piraeus from the Aegean islands over the preceding year in 2015, this was just another point of transit, a node in the course. Six months earlier, ferry operators had begun running additional services from the islands to courier—to contain—the thousands landing there daily on their onward journeys to the mainland. Assemblies of volunteers lined the asphalt alongside the passenger terminals amid sprawls of boxes and trestle tables, readied to furnish the latest boatload with various essentials and accoutrements—packed sandwiches and juice cartons, warm jackets, toothbrushes, a BabyBjörn. Others stood in coloured vests, benignly waving and high-fiving the stream of arrivals as they made their way to the coaches waiting to transport them north to the border, to Europe. It was March 2016 and this had been, until now, largely an exercise in ordering chaos, of packaging, channelling and sustaining the momentum along the conveyer belt—a slapdash logistics. In 2011, EU states had suspended the application in Greece of the so-called Dublin Regulation, a law obliging asylum seekers to apply for refugee status in the first European country they arrive in. So those who had been fingerprinted and registered upon landing in Greece were able to move westward in the EU without fear of being returned to their Aegean point of entry—a country that had been deemed in a court of law unfit to fulfil the human rights of refugees.1

But now, the flow was being interrupted. Travel agencies on some islands had been instructed not to sell tickets for public ferries to asylum seekers. Operators began reducing their services again, with quotas of 200 travellers per vessel imposed. Government-chartered boats, meanwhile, stood docked in port in Lesvos, Chios and Samos. Questions were suddenly being asked, resistance put up further along the production line. Certain classes of traveller were being halted—Iraqis yes, Afghans no—the chain stalling and starting erratically. For Syrians, however, or anyone savvy enough to pass as one (for, in reality, how many Greek officials could tell the difference, or actually wanted to know?), the way was still open. So Salwa and Muataz led the children across the port in the dawn light, towards a bus that would take them to the Macedonian crossing at Idomeni, or to Germany—the blur of place names and geographies along the way was of little relevance anymore. Muataz would still have been limping then, one of the kids clinging onto his back, while Salwa carried the baby and bustled the others along with her typical buoyant pragmatism. The older ones, then seven and ten, were clad in bright puffer jackets, their pale faces crowded out by scarves and woollen hats. It was early spring, but it had been a long winter in the Mediterranean, a long way from their starting point in Homs, and a long war.

*

When it comes to cheap humour, Homs is the Ireland of Syria. Its natives are notoriously derided as the parochial, the dim and the bull-headed of the nation, and any Syrian can reel off at least a couple of Homsi jokes when pressed. In one I am told, there is a big hole in the ground in the centre of Homs. People fall into the hole on a daily basis, injuring themselves or sometimes dying, and so the city mayor sends three local ministers to find a solution. As they stand about scrutinising the hole, the first minister says, ‘Why don’t we just park an ambulance by the hole, and when someone falls in, we’ll drive them to the hospital?’ The second minister shakes his head, tuts and replies, ‘No, no—the nearest hospital is more than an hour away, they will die before they get there! We should just build a hospital here next to the hole.’ The third minister sighs in exasperation. ‘Why do you want to spend all that money to build a hospital just because of a hole?’ he says. ‘It will be much cheaper to fill up this hole and dig another hole next to the hospital already standing an hour away!’

These days, there are more holes than hospitals in Homs. Within one year of the 2011 uprising against Bashar al-Assad, the city’s main state-run medical facility was reportedly being used as a torture centre by regime security forces. Doctors and nurses employed at the facility described security agents chaining critically injured patients to their beds for interrogation, administering electric shocks and beatings. The medical staff were recruited to administer the torture with expert calibration, inflicting the maximum amount of suffering while holding the victim back from the brink of death—or mostly. Employees who refused to collaborate faced serious reprisals. Unable to offer protection against regime raids and assault, medics at other hospitals accepted only emergency cases, tending to patients among shattered windows and bullet-pocked walls. One local nurse from the Red Crescent recounted a regime soldier at a checkpoint telling her, ‘We shoot at them, you save them.’ Outside, the town built over millennia was laid to waste within a few years. More than half of Syria’s third-largest city seemed to melt away under the weight of bombs. All that remained of some neighbourhoods were the abandoned skeletons of structures, while life in others carried on under crumbling awnings and scarred concrete facades. ‘Visitors Valley’, a street near the city centre, came to be known as ‘Death Valley’ due to the frequency with which bodies were dumped there.

A hub on the Roman trade route from Asia to the Mediterranean, Homs evolved into a centre of Christianity during the Byzantine period. As such, it retained one of Syria’s largest Christian populations into the twenty-first century and was often held up as an exemplar of the country’s so-called ‘mosaic’ of religious diversity. Mostly, though, Homs in its modern incarnation was known as an industrial centre, hosting the country’s largest oil refinery—an asset Iran quickly angled to build a replica of on the city’s outskirts, as the Assad regime reconsolidated its control of Syrian terrain in 2017. The city features in my memory only as an indistinct jumble of taxi-crammed streets, swiftly couriered trays of bread and little paper coffee cups, skinny adolescent boys herding passengers onto minibuses—all presided over by the ubiquitous portraits of the Assad clan, in dark glasses and army fatigues. In hindsight, I think now mostly of Homs Military Academy. The country’s oldest and most prestigious military institution, it was founded during the French mandate in the 1930s and has since become near synonymous with Syria’s ruling elite. It was there that Bashar al-Assad was re-groomed for the presidency after, in 1994, being seconded back from a career as an ophthalmologist in London, with the death of his brother (the intended heir to Syria’s leadership). The academy has therefore likewise become emblematic of the sway of the country’s Alawites—a Shia Muslim sect that historically made up around 12 per cent of the population, but has come to dominate its politics and constitute anywhere between 50 and 80 per cent of its military forces. When the senior Hafez al-Assad took power in a 1970 coup d’état, the ruling family wove sect loyalty into the regime, recruiting fellow Alawites to key government and military posts, while siding with other minorities (namely, Christians and Druze) to offer protection against the Sunni Muslim majority. A coterie of affluent Sunni business and trading families were, however, offered generous economic concessions and a share in political influence. The Assad brand of minority rule was, at the same time, veiled by an equally calculated rubric of secular Arab nationalism—a purportedly inclusive, socialism-infused Syrian identity—with the president and his family publicly observing the practices of the Sunni majority. It was this contrivance of secularism, of a distinctly Western cosmopolitanism, that would later enable Bashar al-Assad to pose as a reformer before so many international governments, despite his renegade anti-imperialist rhetoric, as he adopted the mantle of a custodian, the custodian, of a unified Syria. Some locals say that social ties among Sunnis, Christians and Muslims in Homs, with its sizeable Alawite community, were more fluid than in Aleppo or Damascus. Some also say that the city was less fractured by divisions along the lines of sect or ethnicity than its larger counterparts—that, far from being a monolith of regime loyalty, Homs’s Alawites were implicated in the conflict by the regime itself, instrumentalised and militarised, and made to fight for their survival. Others might say too that any factual assertion about religion and politics in the former Syria is now void; that trying to recover some unsullied article of truth from the debris of war is futile.

In April 2011, a series of mass protests, including a rally of some ten thousand citizens in the city’s main Clock Tower Square, saw Homs earn a new reputation for itself, as the capital of the revolution. Protestors, sometimes accompanied by local celebrities, early on attempted to occupy the square, chanting anti-regime slogans and decorating its walls with rallying cries against Assad. They hoped to transform the space into Syria’s Tahrir Square, some said. The regime’s response, however, was unequivocal. Within a few months of the uprising, in Homs alone more than seven hundred killings at the hands of the government army and militias—or shabiiha, ‘ghosts’, as they are commonly known—had been reported. Regime hyperbole about an ‘armed insurrection’ on the country’s streets soon began to unfold in a self-fulfilling prophecy, as the uprising militarised in defence against the crackdown. Defected army officers and opposition fighters, affiliated under the banner of the ‘Free Syrian Army’, fought back against the regime from a maze of storm drains, basements and overrun apartment blocks. The opposition campaign also employed its arsenal of characteristic Homsi humour, citizens now turning it back against the regime. Photos of protesters wearing eggplants and zucchinis strung grenade-style around their waists appeared on social media—a parody of their alleged kit of heavy weaponry. Meanwhile, a Facebook page under the name of ‘Homs International Tank Washing and Lubrication Centre’ offered its services to the multitude of regime tanks and armoured vehicles making incursions into the city. But, as the confrontation between rebels and regime wore on into 3-and-a-half years of siege, much of the city fell into darkness. It was under the cover of a near-complete media blackout that Homs became the stage for some of the fiercest battles and starkest massacres of the war. Locals soon reported eating pigeons and wild plants as the only available sustenance, burning their furniture to keep warm. In May 2014, with swathes of the city already abandoned by residents and rebel-held areas battered by the regime’s relentless air and artillery campaign, Homs’s opposition forces conceded to a ceasefire deal. Fighters and their families were accordingly permitted safe passage out of the city to the rebel-held region of Idlib in north-western Syria. Looking on as the last rebel forces boarded a convoy of green buses waiting to evacuate them from Homs under a 2017 Russian-backed ‘reconciliation deal’, an opposition activist told reporters, ‘the world has failed us’.

*

The family still numbered seven when they got on the bus at Piraeus: Salwa, Muataz and the five kids. I wonder how they sat, who with whom, and what they talked about over the 8-hour journey—or if they talked at all, or just slept, uncompelled by the stretch of motorway, the not-unfamiliar geography of mountains and farmland beyond, the fields of cotton and tomato and grapevine. Fresh produce had been nearing unaffordable when the family left Syria three months earlier, in late 2015. The agricultural land around the town of Idlib, where they had been staying at the time, had been rendered largely useless for purposes other than war, with fighting between the regime and the rebel forces then controlling Idlib leeching into residents’ fields. One morning, Salwa tells me, one of their neighbours went outside to pick tomatoes, only to see her son getting shot twice through the head in the next plot. The woman was too afraid to retrieve his body for two days, so he lay there, bloating among the crops with the other corpses. ‘She lost her mind,’ Salwa says with a click of her tongue, her green eyes wide. She and Muataz had gone with the children to Idlib for a few months to stay with her relatives, to get away from the destruction of their hometown, Homs. They had sold their house, as well as Muataz’s profitable grocery store—they had no plans to return. Anyway, there was not much left of the business to return to then, not since the summer of 2015, when the contents of a regime barrel bomb had torn through the front of the store. Muataz had been sitting there, by the window, and the shrapnel ripped through the left side of his body. He could not move his left arm or leg when he came around, or for the next week or so afterwards while he was in hospital. Eventually, he was able to walk again, but even two years later, his gait is uneven and his left arm hangs limply from the shoulder at an odd angle. So they decided to leave Homs; Salwa had already lost one man in the family to war, her brother having been killed in a suicide truck bombing on the periphery of the city the previous year, and she wasn’t taking any more chances.

She recounts all this to me later, the details relayed not without feeling, but matter-of-factly, in the way that language becomes divorced from its context through repetition, or must become divorced from its context if it is to be repeated. ‘But now the regime is taking back Idlib,’ she explains with a sweep of her hand, ‘it is all gone.’ And what sort of a future was it for the kids anyway, they thought, this war? So, as thousands of others were doing at the time, they paid a smuggler to march them out of Syria to Turkey, where they made their way directly to the coastal town of Bodrum, a hive of British mini-breakers and people smugglers. There, they tried fifteen times to cross by boat to the Greek islands, stymied on multiple occasions, by weather, Turkish police, coast guards, leaky vessels, con artists. After one thwarted departure, they were all made to sleep out amid the pine needles in the forest, hiding from the police, Salwa tells me. She scrolls through her phone to find a photo of the family, taken shortly before attempt number twelve, or was it thirteen? They are all piled together on a brown sofa in a dim-looking hotel room. Only is Salwa smiling, her youthful features warm and indecipherable. ‘Look at the kids’ faces,’ she says, holding the screen up and pointing. ‘They thought they were going to die.’

On the long walk across the mountains of the Syrian border and during their many forays into the scrub along the Turkish coast, Salwa always carried the baby strapped to her front while the youngest clung to Muataz’s back. ‘Like that, we were able to shelter those two a little,’ she explains, making a shielding motion around an invisible infant at her chest, ‘but the other three remember everything. After we left Syria, they were always clinging to me, afraid of getting separated. They have seen a lot.’

The miscellany of transportation must have seemed absurd—or more absurd—through the eyes of a child, unmediated by bureaucratic adult logic: sometimes on foot through wilderness; sometimes in taxis; one day, a leaky dinghy from Turkey at dawn; another, the fresh climate-controlled surrounds of the Blue Star ferry to Athens, with its snack bar and wide-screen TV. And then, after spending five nights in a tent with 150 others near the port of Mytilene on Lesvos, they were on the mainland in a warm bus from Piraeus, watching videos on Salwa’s phone with the free wi-fi. What stories did they tell themselves about all this? They were on their way to Germany, Salwa explained to the older ones, over and again. It was far, but the...