![]()

2 Tourism’s Beneficial Nature: Increasing Tourism’s Capacity to Enhance Conservation in Aotearoa New Zealand’s Protected Areas

MICK ABBOTT1*, CAMERON BOYLE2 AND WOODY LEE1

1Lincoln University, Lincoln, Aotearoa New Zealand; 2The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia

Introduction: The Arm’s-length Relationship of ‘Not Inconsistent’

This chapter considers growing tensions between nature-based tourism and conservation. The geographical focus of this discussion is Aotearoa New Zealand, which, with a growing tourism industry bolstered by ever-increasing visitor numbers, is experiencing more people travelling to its protected areas – especially its world-famous national parks – than ever before. This topic is approached by interrogating the conceptualization of this relationship as it is defined in the country’s legislation, which states that protected areas may be used for tourism so long as it is ‘not inconsistent’ with the conservation of these sites. It is argued that the double negative of ‘not inconsistent’ has institutionalized an arms-length relationship between tourism and conservation in New Zealand which is reflective of a wider disconnect between these two phenomena. This chapter contributes to the academic literature on nature-based tourism by exploring how, within New Zealand’s protected area network, the relationship between nature-based tourism and conservation might be reframed to enable a shift in thinking away from this conceptually limiting binary. The central question guiding this chapter is how might novel nature-based experiences in New Zealand’s protected areas enable a form of tourism which is not only consistent with, but also strengthens, conservation at these sites?

In response to this question, three landscape design projects located at different national parks in Te Wai Pounamu, New Zealand’s South Island, undertaken by Lincoln University and Wildlab in partnership with the Department of Conservation (DOC), the national governmental agency charged with maintaining the protected area network, are examined. These individual case studies have intentionally sought, through the use of design-directed research, to explore ways in which protected areas as key sites in the nature–tourism interface could be reimagined. These case studies bring thinking from the fields of landscape architecture and strategic design to within the sphere of tourism studies, in order to encourage a shift in focus from the critique of nature-based tourism as the consumption of landscape scenery to a more experimental exploration of how tourism could be enlisted as a mechanism that can generate emergent positions in which people, ecology and economy combine in mutually beneficial ways. In the first, Arthur’s Pass Village, within Arthur’s Pass National Park, and its visitor centre are redesigned, turning the latter into a conservation hub through which tourists are expressly inducted into New Zealand’s conservation values and conservation mission. In the second, augmentation, through the use of smartphone technologies, is enlisted to create a visitor experience at the Oparara Arch within Kahurangi National Park, based on past extinctions of indigenous bird species and the need to protect living ones that are threatened. In the third, a retired pilot mining site in Punakaiki adjoining Paparoa National Park is transformed into a nature reserve directly through the active crowdsourcing of tourists to participate in ecological restoration.

Visiting Nature: The Relationship between Tourism and Conservation

Tourism landscapes and conservation landscapes have become strongly interwoven in New Zealand. The country’s protected area network, comprised of a range of sites including its national parks, covers 8.5 million hectares, equating to one-third of its total land area or the combined territories of Switzerland and the Netherlands (Molloy, 2007). This has resulted in it being one of only a few countries that can claim to meet the targets established by the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (UNCBD, 2017), which require 17% of the land area of participating nation-states to have biodiversity protections. New Zealand also has a number of world-leading species restoration programmes underway within its protected areas, which aim to conserve various threatened indigenous bird species (DOC, 2020). At the same time, the country is experiencing high levels of economic growth, particularly in tourism, which is now its single largest export industry and within which there is a strong focus on nature-based tourism (Statistics New Zealand, 2019). In 2018, 1.75 million international tourists to New Zealand travelled to a national park at least once while they were present in the country (DOC, 2018a). This is in part due to the success of the government’s long-standing national tourism marketing campaign, which brands the country with the ‘100% Pure New Zealand’ slogan and represents it visually with images showcasing the beauty of its natural landscapes: from pristine golden-sand beaches to wild temperate rainforests and sublime alpine environments (Calder, 2011). Several of New Zealand’s national parks also form World Heritage Sites listed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2020), which strengthens their global appeal. New Zealand’s vast and varied protected area network is now as much about tourism and the recreation that takes place there, as it is conservation.

New Zealand’s significant efforts to conserve its natural landscapes and their ecology, while also utilizing them to develop its growing tourism industry, means its protected area network can be considered a key site in nature–tourism issues. Internationally, nature-based tourism is routinely framed around the effective management of adverse impacts on environmental factors such as biodiversity, natural quiet, overcrowding and remoteness, through strategies to avoid, remedy or mitigate them (Leung et al., 2018). New Zealand is certainly similar to many other countries in this regard. This approach is clearly laid out in the country’s legislation, as the Conservation Act states that the function of DOC is:

to manage for conservation purposes, all land, and all other natural and historic resources, for the time being held under this Act … to the extent that the use of any natural or historic resource for recreation or tourism is not inconsistent with its conservation. [emphasis added]

(New Zealand Government, 1987, p. 24)

Other key government documents on protected areas, including the National Parks General Policy, the Conservation General Policy, the DOC Visitor Strategy, as well as more regionally and locally focused Conservation Management Strategies and National Park Management Plans, are all strongly aligned with this approach. They all aim, for example, to allow tourism or foster recreation, as the Conservation Act stipulates, so long as such practices are, again, ‘not inconsistent’ with conservation (New Zealand Government, 1987).

The growing tension between nature-based tourism and conservation has become increasingly evident in New Zealand, just as it has in many locations around the world. In New Zealand, DOC lacks adequate resources to maintain the country’s protected area network for the dual purposes of both conservation as well as tourism and recreation. The population of New Zealand is very small compared with its land area, resulting in a ratio of 1.82 hectares of protected area per person and, on average, only NZ$21 of taxpayer funds per annum for the ecological conservation of each hectare (DOC, 2018b). Moreover, DOC has a permanent staff totalling 2000 people, resulting in a significant lack of human resourcing (DOC, 2017). As the Conservation Act clearly states, DOC has to prioritize its use of this minimal funding to attempt to meet challenging conservation goals within the country’s protected areas while trying to fulfil its supporting obligation to also manage these sites for recreation and tourism activities, including the provision of tracks, huts, visitor centres and other facilities (New Zealand Government, 1987). At the same time, there is increasing concern among some New Zealanders about the negative impacts of tourism growth on the country (Tourism New Zealand, 2016).

As outlined here, the conventional framing of the relationship between tourism and conservation situates the two as being in perpetual tension with one another and, in terms of protected areas, this plays out in ways which only reify this deeply embedded belief, such as the direction of related policy or funding for related government agencies. The subsequent strategies that are generally offered to address this issue seek to ensure that tourism growth does not compromise conservation efforts through one of three normative responses or a combination of these: (i) to increase resourcing for conservation goals; (ii) to restrict or reduce tourism visitation; or (iii) to make tourism practices more sustainable (Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, 2019). Such solutions further institutionalize the binary division that frames tourism and conservation as being in opposition to one another and at best only capable of coexisting through the double negative of ‘not inconsistent’. Applying this thinking to the context under discussion would lead to consideration of how DOC could be better resourced to support tourism in New Zealand’s protected areas while still achieving conservation goals within them or, conversely, how such tourism could be restricted, reduced or made more sustainable to achieve the same result. In contrast, the following examples explore how tourism and conservation can be mutually beneficial within the context of New Zealand’s protected areas.

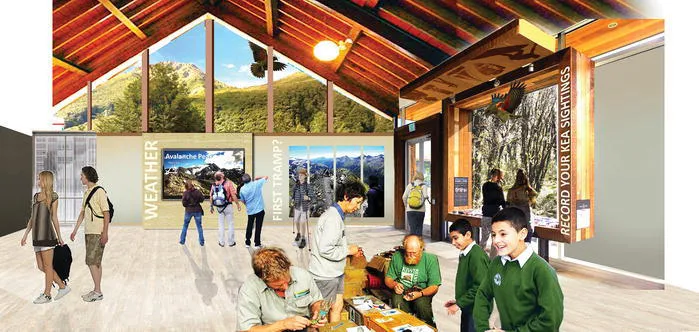

Arthur’s Pass National Park: Visitor Centre Conservation Hub

In this project, the village and visitor centre at Arthur’s Pass National Park are redesigned to shift them from operating as a tool used to market New Zealand as a scenic place to view nature as a spectacle to instead become a conservation hub (Fig. 2.1).1 Landscape architect James Corner (2014) critiques the scenic overlook common in many North American national parks, which portrays them as places without substance. Arguably, protected areas in more touristic settings have been constructed as entertainment sites that provide recreation, adrenaline and nature as a spectacle (Corner, 2014). It has been identified that a number of visitors to New Zealand want to participate in conservation while they are there (Tourism New Zealand, 2018). However, there are few opportunities for visitors to the country to have nature-based tourism experiences that are not focused on the consumption of landscape. The limited number of tourism experiences in New Zealand which are centred on conservation tend to involve practices such as trapping pest animals and removing invasive plants in remote wilderness areas (Beeton, 1998). Such experiences generally require high levels of physical fitness and ability, as well as prerequisite outdoor skills and knowledge. The purpose of the redesign of the village and visitor centre, by contrast, is to engage a larger pool of international tourists who may be curious about conservation in New Zealand but have little understanding of the topic, nor opportunities to participate.

Fig. 2.1. Arthur’s Pass National Park Visitor Centre Conservation Hub. (Photo: the authors.)

The visitor centre was redesigned to shift its role as a site of information and interpretation regarding the surrounding area for tourists to one where primary conservation knowledge and skills are learnt that are relevant to the protection of ecology in the park itself and the urban environments where most people are from. Interactive elements at the centre which aim to achieve this include a ‘friend or foe tracking tunnel’ section, which explains to visitors how rangers set up and use tracking tunnels within the park to identify the movements of pest animals and how these can be distinguished from protected species. In addition, the ‘do-it-yourself conservation’ section teaches visitors how to set up a trap at home in their own backyard as a citizen science project, which will as...