- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

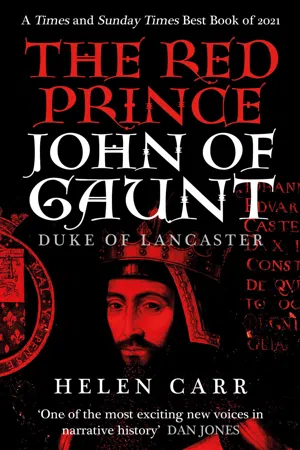

War, revolution, treason and love – the thrilling tale of Sir John of Gaunt brought to life by medieval history's rising star.

‘The Red Prince announces Helen Carr as one of the most exciting new voices in narrative history.’ Dan Jones

Son of Edward III, brother to the Black Prince, father to Henry IV and the sire of all the Tudors. Always close to the English throne, John of Gaunt left a complex legacy. Too rich, too powerful, too haughty… did he have his eye on his nephew’s throne? Why was he such a focus of hate in the Peasants’ Revolt?

In examining the life of a pivotal medieval figure, Helen Carr paints a revealing portrait of a man who held the levers of power on the English and European stage, passionately upheld chivalric values, pressed for the Bible to be translated into English, patronised the arts, ran huge risks to pursue the woman he loved… and, according to Shakespeare, gave the most beautiful of all speeches on England.

***

A TIMES AND SUNDAY TIMES BEST BOOK OF 2021. SHORTLISTED FOR THE ELIZABETH LONGFORD PRIZE FOR HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY

‘In Shakespeare’s Richard II, John of Gaunt gives the “this scepter’d isle… this England” speech. This vivid history brings to life his princely ambitions and passion.’ The Times, Best Books of 2021

‘Superb, gripping and fascinating, here is John of Gaunt and a cast of kings, killers and queens brought blazingly, sensitively and swashbucklingly to life. An outstanding debut.’ Simon Sebag Montefiore

‘Helen Carr is one of the most exciting and talented young historians out there. She has a passion for medieval history which is infectious and is always energetic and engaging, whether on the printed page or the screen.’ Dan Snow

‘The Red Prince announces Helen Carr as one of the most exciting new voices in narrative history.’ Dan Jones

Son of Edward III, brother to the Black Prince, father to Henry IV and the sire of all the Tudors. Always close to the English throne, John of Gaunt left a complex legacy. Too rich, too powerful, too haughty… did he have his eye on his nephew’s throne? Why was he such a focus of hate in the Peasants’ Revolt?

In examining the life of a pivotal medieval figure, Helen Carr paints a revealing portrait of a man who held the levers of power on the English and European stage, passionately upheld chivalric values, pressed for the Bible to be translated into English, patronised the arts, ran huge risks to pursue the woman he loved… and, according to Shakespeare, gave the most beautiful of all speeches on England.

***

A TIMES AND SUNDAY TIMES BEST BOOK OF 2021. SHORTLISTED FOR THE ELIZABETH LONGFORD PRIZE FOR HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY

‘In Shakespeare’s Richard II, John of Gaunt gives the “this scepter’d isle… this England” speech. This vivid history brings to life his princely ambitions and passion.’ The Times, Best Books of 2021

‘Superb, gripping and fascinating, here is John of Gaunt and a cast of kings, killers and queens brought blazingly, sensitively and swashbucklingly to life. An outstanding debut.’ Simon Sebag Montefiore

‘Helen Carr is one of the most exciting and talented young historians out there. She has a passion for medieval history which is infectious and is always energetic and engaging, whether on the printed page or the screen.’ Dan Snow

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Red Prince by Helen Carr in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One

This England

This royal throne of Kings, this sceptered isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise,

This fortress built by Nature for herself

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in the silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands,

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England.

John of Gaunt in Richard II, Act II, Scene I

In the mid-fourteenth century, the Channel was a dangerous stretch of water. French ships patrolled the sea, attacking English coastal towns in an attempt to destroy the lucrative wool trade between England and Flanders. In 1340, England and France were three years into a political, dynastic and territorial struggle – a war of succession – that would become known as the Hundred Years War. By summer 1340, both sides were yet to engage in full battle. On 24 June 1340, a ‘Great Army of the Sea’ dropped anchor outside the port of Sluys, the inlet between Zeeland and Flanders, and prepared for combat. The ships were filled with French and Genoese warriors and their intimidating presence incited mass panic along the coastal towns of the Low Countries. Local people either feared attack and fled their homes, or flocked to the coastline to see the spectacle for themselves.

As French ships floated outside Sluys, the King of England, Edward III, led a fleet across the Channel, intending to land an army ashore in Flanders and oust the French who had infiltrated the country in his absence. Two months earlier, Edward had left his heavily pregnant Queen, Philippa of Hainault, in the Flemish town of Ghent where he spent months trying to make an alliance with Flanders. To secure the terms, he was forced to sail back to England, promising to return with an army and money. Philippa – expecting her sixth child – stayed behind as collateral for the enormous loan the Flemish had given the English King to begin his war.

The French King, Philip VI – the first of the Valois family – anticipated Edward’s return to Flanders and mustered a fleet so vast that it would not only block Edward’s landing but threaten the total annihilation of the English naval force. In May 1340, news of this mighty French fleet, floating off the coast of Flanders, reached Edward III as he held a Royal Council at Westminster. Senior members of the English nobility and clergy shouted over one another. Some proposed battle, but the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Stratford, argued against it. He was cautious and warned the King that the French force was too large to be defeated.

Despite reservations from his Council, the King set about mustering the greatest English fleet to ever sail across the Channel. Coastal towns and ports throughout England were to be stripped of all ships and provisions, to be sent to Orwell in Suffolk where ships prepared to set sail.

At dawn on 22 June 1340, Edward III was on board his cog ship – a merchant vessel with one sail – as it passed Harwich on the south-east coast of England, leading a fleet of around 150 vessels. The naval force was cobbled together from warships, merchant ships and even large fishing boats. They were blown forwards by a north-westerly breeze, towards the superior fleet of French ships, and finally came in sight of the enemy at the mouth of the river Zwin two days later. The sheer scale of the French force was overwhelming – described by the chronicler Jean Froissart as a water fortress. A mass of wooden breastworks, barriers and masts bound together by chains: ‘like a row of castles’.

The English fleet, though unprecedented in size, should have been no match for the French. Many of the English vessels were ill-equipped for battle and they were faced by an impenetrable stockade. Alongside six Genoese galleys, the French component of the fleet was led by a Breton knight, Hugues Quiéret, Admiral of France, and Nicolas Béhuchet, its Constable – the commander in chief of the French army.

At around 3pm, Edward III gave the order to advance on the French ships lingering on the horizon. However, at the sight of armoured prows and piercing masts, the morale of the English dwindled. As he paced the deck of his ship, the King delivered an inspiring oration to boost his men. He expounded that their fight was in the pursuit of a ‘just cause, and would have the blessing of God Almighty’. He also permitted his men to keep whatever booty they could obtain from the enemy vessels.1 The incentive of plunder appears to have lifted the mood, for his army soon became ‘eager’ to face the imposing force ahead and battle drums echoed across the water.

The French ships were bound together to create a single juggernaut that could crush lone vessels in the water ahead. The English would have to break their defence in order to engage. According to the French Chronicle of London, Edward ordered his men to flee – as the French watched. The English drew their sails to half-mast and raised anchor, as if to turn back. As Edward anticipated, the French immediately played into his hands; they ‘unfastened their great chains’ and pursued the English in anticipated triumph. The French ships, detached from their intimidating unit, were now vulnerable, and proved easy pickings as the English vessels turned back and attacked. To the sound of drums and trumpets, signalling battle, heaving ships crashed into one another, throwing men off their feet with the force of the collision. Both sides boarded each other’s vessels and so began close and bloody combat. ‘Our archers and crossbowmen began to fire so thickly, like hail falling in winter, and our artillerymen shot so fiercely, that the French were unable to look out or to hold their heads up. And while this flight lasted, our English men entered their galleys with great force and fought hand to hand with the French, and cast them out of their ships and galleys’.2 In tricking the French into breaking up their fortress of ships, the English were able to beat the odds and trap the French. The result was a rout, described by Jean Froissart as ‘a bloody and murderous battle’. Edward III was wounded in the leg, but his injury was minor in comparison to the fate of the French commanders. Hugues Quiéret died fighting and the Constable of France, Nicolas Béhuchet, was strung up from the mast of his own ship.

The Battle of Sluys was a triumph for Edward III, for he had prevailed in one of the largest and most crucial naval battles of the Hundred Years War, winning him what became known as the English Channel. This victory was so deeply etched into Edward III’s self-image, it was commemorated on a valuable gold noble, depicting Edward ensconced in a ship, gallantly clutching his great sword and shield, branded with the quartered arms of England and France.3

As the King of England celebrated his great victory into the night, his Queen, Philippa of Hainault, was still in recovery from her own bloody and highly dangerous experience: childbirth. Childbirth in the fourteenth century was an agonising and fraught event, accompanied by ritual, prayer and carefully considered practicalities. Managed exclusively by women, those in charge of the safe delivery of a royal baby – and the survival of a Queen – were highly skilled midwives. Two months before the Battle of Sluys, in a dark, hot room in the Abbey of Saint Bavon, in the small town of Ghent, the Queen of England delivered a ‘lovely and lively’ baby boy, named John Plantagenet.4 After the battle, Edward III made his way to Ghent, but en route he diverted his men to the Shrine of the Lady of d’Ardenburgh, where they abandoned their horses and walked on foot to the shrine. On his knees, the King of England gave thanks for the great victory at Sluys and for the safe delivery of another healthy Plantagenet prince.5

Thirteen years before the birth of John Plantagenet, in the cold winter of 1327, his grandfather King Edward II was murdered. Unceremoniously ousted from his throne and imprisoned at Berkeley Castle, the King of England was then dispatched: the names of his murderers and their method remain a mystery. The popular myth that surrounds his death whispers that he was impaled through the rectum with a red-hot poker; a cruel and brutal death for an accused sodomite. Edward II had been overthrown in favour of his young son, Edward – later Edward III – in a rebellion led by his wife, Queen Isabella, and her lover, Roger Mortimer. They believed that the impressionable new King would be a malleable puppet in their schemes, and that they would be well placed to control the realm as regents (in all but name) for the young Plantagenet heir.

Edward III was crowned aged fourteen on 1 February 1327, and began his kingship under the watchful eye of his mother and the seemingly unstoppable Roger Mortimer. The young King tolerated Mortimer for three years, until 1330, when Edward conspired with his closest friends at court to overthrow the man who really controlled the country. On 19 October, in a coup against his effective stepfather, Edward captured Mortimer at Nottingham Castle and dragged him outside, to the sound of his mother’s screams: ‘Fair son, have pity on the gentle Mortimer’. Without mercy, he ordered that Mortimer be imprisoned and tried. With Edward’s agreement, Mortimer was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered.

On 29 November, Roger Mortimer was dragged to the scaffold at Tyburn on a hurdle and tied to a ladder before the crowd. His genitals were then severed and his stomach was slit, with his entrails yanked free from his open belly before being cast into a fire. Finally, Mortimer’s head was cut off and he was hung by his ankles.6 The bloody, headless corpse of the old power in England demonstrated the birth of a new era: the age of Edward III. Very few shed tears for the man who saw himself as King, or for the Dowager Queen. Isabella was left bereft, mourning quietly in confinement and visited by her son only once or twice a year.7

Shortly after the Nottingham coup, Edward III released a proclamation which he commanded be read by sheriffs aloud and in public throughout the realm. ‘[Edward] wills that all men shall know that he will henceforth govern his people according to the right and reason, as befits his royal dignity, and that the affairs that concern him and the estate of his realm shall be directed by the common counsel of the magnates of his realm and in no other wise . . .’8 The King’s statement made clear that ‘royal dignity’ went hand in hand with royal authority: he believed in providential kingship.

As he took control of the country in his own right, Edward first had to tackle domestic affairs. When Edward inherited the throne, he also inherited a country in a sorry state. Scotland presented the principal threat, with its King, Robert the Bruce, frequently attacking England’s northern border. Wales had been colonised by Edward I and overrun by the English, with a legacy of lingering resentment amongst the Welsh, while Ireland was left largely to its own devices. In 1332, the House of Commons formed after sitting together for the first time in a separate chamber to the lords and clergy. The Commons were made up of country representatives – knights of the shire from the countryside and burgesses from the towns and cities. They were elected locally, whereas lords received direct summons from the King for Parliament. By 1341, the Commons were independent of the clergy or the lords for the first time, which enhanced their position and power as spokesmen for the people. Magnates were appointed to defend the realm, and allocated the responsibility of mustering troops from their county. Edward of Woodstock – the Black Prince – was installed as Prince of Wales, and successfully recruited Welsh soldiers when the time came for war. Edward III strengthened the northern borders against the Scots and later placed his son Lionel in the position of Lieutenant in Ireland.

Despite domestic affairs being of supreme importance, war with France was inevitable. This was in part due to Edward’s forceful and ambitious nature, but also down to an old dispute over territory. Edward III had not only inherited the English crown, but the constant monarchical belief that the lands in France that had once been Plantagenet territory were still by right English. The largest and most significant instigator of the Hundred Years War was the disagreement over Gascony.

Gascony was a treasured fraction of what had once been a Plantagenet domain in France. It was also incredibly lucrative and produced the most popular wine in England. Gascony was, above all, a fiscal asset to the Crown. In 1259 Henry III made peace with Louis IX with the Treaty of Paris, and in doing so renounced Plantagenet claim over lands lost in France. It was agreed that Gascony could be kept, but only in fief – held in return for allegiance or service – to the French crown. Edward I, II and now Edward III refused to acknowledge this agreement, causing an enduring friction between England and France.

This tension came to a head when, in 1337, Philip VI confiscated the Duchy of Aquitaine, a region in the south-west of France, bordering the Kingdom of Navarre, and the county of Ponthieu, an original Norman vassal state at the mouth of the Somme – accusing Edward of breaking his feudal bond. Edward responded with an outright claim of what he considered to be his birthright: the French throne. He was, he asserted, the closest male heir of the late Charles IV of France, through his mother Isabella.

As war with France grew imminent, England began to prepare for combat, mustering troops from around the country. In order to defeat the French, Edward was aware that he needed international allies and sought the support of Fla...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise for The Red Prince

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Money

- Introduction

- Prologue

- Map of France in the Fourteenth Century

- Map of The Iberian Peninsula in the Fourteenth

- 1 This England

- 2 The Glory of War

- 3 Fire and Water

- 4 The Bleeding Tomb

- 5 Death, Duty and Dynasty

- 6 Cat of the Court

- 7 Enemy of the People

- 8 The Rising

- 9 Noble Uncle, Lancaster

- 10 King of Castile and Leon

- 11 Peacemaker

- 12 Time Honour’d Lancaster

- Epilogue

- John of Gaunt’s legacy: a family tree

- A Note on Sources

- Acknowledgements

- Plate Section

- Further Reading

- Notes

- Imprint Page