![]()

Chapter 1

ORIGINS

Experiments within Tradition

It is difficult to find just one event, new composition, provocative painting, or cultural movement that directly led to the radical changes in the arts at the onset of the twentieth century. We can, however, look back at a cluster of historical events that still reverberate in today’s world, ones that significantly influenced artists and composers during the first quarter of the twentieth century.

In 1916, a group of artists and poets banded together and declared their discontent with bourgeois society. They met at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, Switzerland, where they adopted the nonsensical name “Dada” as their moniker. To bring attention to the group, the Dadaists, as they were called, issued a manifesto in 1920 stating that the group’s intent was to reject the “established modes of artistic rendering” and, with great fanfare, embraced “nothing” as a new standard for the arts. They proceeded to “take past and present and make fun of everything in it by parody, pastiche, ridicule, and desecration.” The Dadaist poet Tristan Tzara (1896–1963) invented “chance poems” in 1919. His approach was as follows: “A newspaper article is cut up into separate words. These are shaken in a bag, and then copied in the order in which they are removed from it.” (Later in the century, composer John Cage would use similar “chance methods” as an approach to composing.) It was in 1913 that the French artist and Dadaist Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) mounted a bicycle wheel upside down on a stool. The following year he chose the first “readymade,” a bottle-rack from a local hotel, exhibiting both bike and rack as “objets d’art.” From 1915 to 1923, Duchamp worked on a unique multidimensional work titled The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass). Of significance to percussionists were Duchamp’s directions indicating that this particular work could be realized as a musical composition. “Duchamp states that the composition may be performed on a player piano, mechanical organ or any other new instruments for which the virtuoso intermediary is suppressed.” (Using chance operations, a multiple-percussion realization with instruments made from glass was performed by Donald Knaack on February 5, 1976, in Buffalo, New York.)

Another group of artists who, like the Dadaists, rejected the artistic standards of the time called themselves Futurists. Founded in 1909 by the Italian poet Fillippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876–1944), the Futurist movement embraced whatever was new, dangerous, and exciting, for example, automobiles, airplanes, film, and radio. Skillful propagandists, they staged provocative multimedia performances to provoke and challenge a complacent middle-class listening audience. Futurists often mounted performances that included simultaneous acts, events that incorporated incidental music, avant-garde poetry, and dance along with a display of Futurist paintings. The goal was to create controversy and bring attention to their cause. “To shock and outrage was much a part of the modernist movement in the visual arts” and in music. These public events were a precursor of the so-called “happenings,” multi-artistic events that became popular for a short period of time in the 1960s and 1970s.

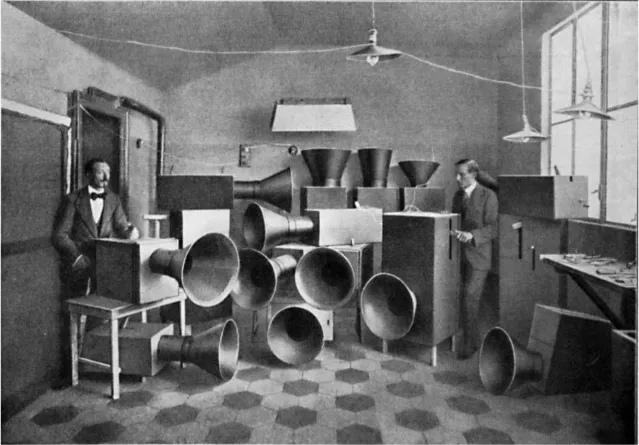

One member of the Futurist group, Luigi Russolo (1885–1947), a painter turned musician, conceived and built several sound-producing instruments he called “intonarumori.” These mechanical instruments were capable of producing a variety of sounds that Russolo categorized into six families, including one for percussion sounds. Unfortunately, the instruments did not survive the ravages of World War II. In photographs, we see instruments that appear to be large wooden cabinets with cylindrical horns mounted in front to aid sound projection. Without significant amplification, the instruments were reported to be difficult to hear. In one photo, a rear view shows a mounted cymbal inside the cabinet. In other photos, the players are pictured standing behind each machine with their hands on levers that purportedly controlled pitch and volume. Orchestra music written by Russolo, Francesco Balilla Pratella (1880–1955), and other Futurist composers incorporated the intonarumori into their scores using graphic notation (mainly lines of various heights, thicknesses, and lengths) to indicate pitch, volume, and duration. Starting in 1914, Futurist concerts were given in halls throughout Europe; these events aroused the interest of the musical establishment. “Russolo’s concerts in the early 1920s still caused fierce controversy, but impressed several outstanding composers, including Maurice Ravel, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, and the prophet of future Avant-gardes, Varèse.”

Image 1.1. Luigi Russolo and Ugo Piatti in their workshop in Milan. Photograph from Luigi Russolo, L’arte dei rumori (Milan: Edizioni futuriste di “Poesia,” 1916).

Even before the Dadaists and Futurists, one composer caught the attention of fellow composers as well as the public with his provocative compositions for the dance. The Russian-born composer Igor Stravinsky’s (1882–1971) three works for ballet, L’Oiseau de feu (The Firebird, 1910), Pètrouchka (1911), and Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1912) gained international acclaim with the last work causing the audience to riot at its Paris premiere. Its notoriety did not escape the attention of composers. “The reception of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in Paris had given not only new cachet to such reaction in the musical world but also a model to emulate.” To the public, the work seemed violent. It rejected traditional tonal structure, relying instead on shifting rhythmic and metrical patterns to provide forward motion. Heavily percussive, it marked a pivotal point in twentieth-century music. Aaron Copland writes, “The key work of this period is, by common consent, Stravinsky’s ballet of pagan Russia, The Rites [sic] of Spring, composed for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes in 1913. This is not the composer’s most perfect work, but it is certainly his most strikingly original composition.”

Born in Russia, near St. Petersburg, Stravinsky became interested in music at an early age (his father was a singer). Though he studied law, his passion for music eventually led him to a career as a composer. At the University of Heidelberg, he became friends with the son of the noted Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908) and became a regular guest of the family household. Stravinsky “began taking regular lessons in orchestration” from Rimsky-Korsakov who tutored him free of charge. He considered Rimsky-Korsakov both teacher and mentor and the influence of the composer of Scheherazade is evident in Stravinsky’s skillful orchestrations, including his writing for percussion. “A signal change in Stravinsky’s fortunes came when the famous impresario Diaghilev commissioned him to write a work for the Paris season of his dance company, the Ballets Russes.” The result was the production of Stravinsky’s first ballet, titled The Firebird. His association with Diaghilev, though strained at times, continued until the ballet master’s death in 1929.

Though Stravinsky’s percussion scoring in Le Sacre du printemps included some innovative features, it continued to use timpani and other percussion instruments in the fashion of the time, namely to outline the beat (albeit with a great deal of force), to add color to a passage (tambourine and antique cymbals), and to provide punctuation to musical phrases (bass drum and timpani). With its fast tempi, mixed meters, sudden tempo changes, loud dissonant chords, and polytonal passages, Sacre challenged both player and listener.

The instrumentation for Le Sacre du printemps requires an unusually large wind and brass section including four oboes, four bassoons, and eight horns. The percussion section calls for six players, plus two timpanists. Five kettledrums, including a piccolo timpano for a high B-natural, are required. Instructions in the score direct the second timpanist to assist in tuning the drums so that the principal player can “follow the beat.” Today, many professional timpanists have designed individual approaches to the part, enabling a single player to cover most of what Stravinsky wrote. Musically this is helpful since a number of dramatic gestures over four drums are best played in a soloistic manner. The timpani part also indicates that the drums are to be played with snare drumsticks (wooden sticks) in specified passages. (Fig. 1.3)

The section-percussion parts cover the following: triangle, guiro, tam-tam, bass drum, tambourine, and cymbals antique (crotales). Though orchestrated primarily in the traditional manner, Stravinsky does explore some unusual approaches for this group of instruments. At one point he notates the triangle to be played fortissimo, striking it with a wooden stick. (Fig. 1.1) For the guiro he carefully notates the stroke direction, specifying both up and down strokes (Fig. 1.2) and for the tam-tam, which in most works of the times was used sparingly, if at all, Stravinsky creates long ostinato patterns. Performing the tam-tam part requires great sensitivity and control so as to allow the steady rhythmic line to be heard on the beat, not before or after it. A startling effect is created when the tam-tam is forcefully scraped with a metal triangle beater along its edge. (Fig. 1.3) The bass drum is to be played with a normal beater and with snare drumsticks when indicated. At one point in the “Danse de la terre” (“Dance of the Earth”), the bass drum articulates a three-against-four rhythmic scheme in conjunction with the timpani. Rapid crescendi and sharp accents make the part demanding. (Fig. 1.4) Stravinsky scores the tambourine in traditional manner, uniting it with the English horn to evoke the exotic East in the section titled “Action Rituelle des Ancêtres” (“Procession of the Wise Elders”). Cymbals antique, played forte, add to the cacophony in the “Dance of the Adolescents.” (Fig. 1.1)

To summarize, when scoring Le Sacre du printemps, Stravinsky used timpani, bass drum, and tam-tam to enhance the powerful rhythmic drive of this famous composition. He also demonstrated his ear for new and unusual color effects such as the tam-tam glissando and the use of wood on the triangle. Overall, Stravinsky’s use of percussion in his three ballets was a small, but noteworthy, step in the evolution of scoring the orchestra’s battery section. Of the utmost importance was Stravinsky’s contribution to helping make the percussionist an equal partner with other instrumentalists, as demonstrated in his dramatic chamber work Histoire du soldat (A Soldier’s Tale).

In 1917, historical events in Russia dramatically changed Stravinsky’s life. In that year, revolutions occurred that toppled the ...