- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Born in Sondrio, Italy, in 1891, Pier Luigi Nervi was a pioneer in the engineering and architecture of reinforced concrete. His buildings showed how the use of reinforced concrete expanded the possibilities of form and structure. His methods, meanwhile, ingrained his structures with patterns that came directly out of his economical, manual construction processes. The results were buildings that matched awe-inspiring spans with surprisingly human scale.

Beauty's Rigor offers a comprehensive overview of Nervi's long career. Drawing on the Nervi archives and a wealth of photographs and architectural drawings, Thomas Leslie explores celebrated buildings like Palazetto dello Sport built for the 1960 Rome Olympics, St. Mary's Cathedral in San Francisco, and the UNESCO headquarters in Paris. He also sheds new light on unbuilt projects such as the Pavilion of Italian Civilization for the Universal Exposition of Rome E42. What emerges is the first complete account of Nervi's contributions to modern architecture and his essential role in a revolution that realized concrete's potential to match grace with strength.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Beauty's Rigor by Thomas Leslie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Background

Last week Engineer Nervi’s latest building, Rome’s Palazetto dello Sport, was in full operation with a solid calendar of basketball games, boxing matches, and fencing competitions. Neither the appreciative spectators, gazing at the soaring, concrete-ribbed dome free of any obstructing pillars, nor the art critics, who praised it as “a masterpiece of creative genius … perfection” would believe that Nervi had no esthetic scheme in mind. But it was a fact that he had merely worked out an orderly system for transmitting the flow of the great dome’s stress along the most logical and economical lines. … An artist to his fingertips, Engineer Nervi protests that his buildings, which he likes to call “coverings” or “space limits,” are simply “a rigid interpretation of structural necessities.” Says he: “Beauty does not come from decorative effects, but from structural coherence.”

—Rosamond Bernier, “Poetry in Concrete”

The Palazetto dello Sport, the smaller of two indoor arenas designed and constructed by Pier Luigi Nervi for Rome’s 1960 Olympics, was an assertion of Italian pride and recovery; just a dozen years after World War II ended, the country had been awarded the Games as a symbol of the country’s recovery and reentry into the global community. Italy was one of the brightest, best-performing economies in the world, and it had already earned a reputation for sophisticated design. From Olivetti typewriters to Ferrari automobiles, Italian had become an adjective for well-crafted, thoughtfully designed, stylish goods. The Palazetto was just the latest design triumph for the country, and its engineer and builder, Pier Luigi Nervi, fulfilled the international press’s image of the Italian design maestro: stylish; fluent in the languages of manufacturing, building craft, and fine art; able to reel off a pithy quote that hinted at greater poetic and philosophical meanings behind the deceptively simple object at hand. Yet the ease with which Nervi spoke about his work masked a calculating mind, a competitive business sense, and an intensity that had marked his ascent from prosaic professional beginnings. Even the graceful Palazetto, with its mesmerizing, sunflower-like roof, had come about through Nervi’s artful skill at winning competitive bids. Commissioned even before Rome had been awarded the Olympics, the project had been a gamble by its designers and its clients. Nervi had helped to assemble the tender documents, which favored his patented construction processes. No other builder could compete with his firm’s bid. Like many of Nervi’s buildings, the Palazetto’s poetic grace and simplicity emerged from very worldly circumstances.

FIGURE 1.1. Palazetto dello Sport, Rome, 1957. (Photo by the author)

Nervi’s emergence on the international scene in the 1950s and 1960s came at a hopeful moment for architecture and engineering. Optimism about the postwar successes of urban planning, affordable materials such as aluminum and high-strength steel, the reconstruction of Europe’s cities and towns along scientific lines, and new constructive types such as the curtain wall and the space frame promised unlimited possibilities for the postwar world. These developments occurred at a sanguine moment in the cultural perception of science and technology. Salk’s polio vaccine, the harnessing of nuclear energy, and the construction of vast works of public infrastructure all offered hope for tangible advances in daily life. The world was primed during these decades to welcome a figure who embodied the optimism inherent in such technical progress, especially one who was as fluent in the quantitative achievements of the sciences as in the cultural traditions of a reemergent Europe. C. P. Snow’s 1959 lament on the distance between the “two cultures” of the sciences and the humanities highlighted the global hunger for figures who could bridge this gap. An architect-engineer whose innovative, technically advanced approach could also recall in viewers’ minds the vaults of the Romans and the domes of Baroque Italy, whose designs felt equally at home in Rome, Paris, New York, Montreal, and Sydney, and whose writings were full of literate allusions to architectural history and to detailed descriptions of shell engineering, was destined for international acclaim in such a climate.

Nervi was well-read in the classics and in engineering theory, literate in his writing, fluent in static conceptions and architectural composition, and fascinated by the history of architecture and by current developments in concrete and steel design around the world. His designs synthesized movements in the arts, the sciences, and Italy’s industrial climate into works that were evocative and engaging even for those who might not make the historical links between his 1957 dome for the Palazetto and that of the Pantheon, for instance, a mere 4 kilometers away. Nervi’s best works were evocative in a way that appealed to specialists and the public alike. One may not have understood the cultural allusions or the sophisticated structural or constructional techniques involved, but Nervi’s spaces—in particular his public spaces—never failed to captivate. Time magazine extolled his ability to “raise pure structure to art” and to make raw concrete “compete with marble” for sheer architectural beauty.1 Winthrop Sargeant’s 1960 profile for the New Yorker called him a “virtuoso” in reinforced concrete, whose structures were “as exciting … as a soprano’s perfectly placed high C or an athlete’s powerful, controlled broad jump.”2

Such comparisons to Nervi as an artist or an athlete, a musician or a poet were common throughout his career, but references to him as an architect were technically incorrect. Nervi was trained as an engineer and builder. He had no formal educations or qualifications as an architect, although his sons Vittorio (1930–) and Antonio (1925–1979) did. In conversation he referred to himself as “an engineer in the contracting business” and to his buildings as “coverings.” This did not stop others from comparing him to the great master builders of the era—Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright, Alvar Aalto, among others—but Nervi’s practice and his built work presented a thorough challenge to typical architecture as practice during the era. Nervi insisted that his forms arose not from sculptural ideals or historic precedent but rather from ironclad economic and static logic. The signatures of their creation were to be found more in the marks of their constructive processes than in their overall forms or appearances.

It is easiest to place Nervi in the pantheon of twentieth-century engineering, among those who pioneered and developed the techniques of thin-shell concrete construction. Like Robert Maillart, Eduardo Torroja y Miret, and Félix Candela, Nervi’s greatest engineering contributions came with his incredible roof spans, achieved with thin structures in which economy and inherent visual appeal were intertwined. Two of Nervi’s domes—the Palazetto dello Sport and the Norfolk Scope Arena—set engineering records for clear-span concrete domes. Only Torroja, however, matched Nervi in producing a published philosophy. Nervi wrote in structural engineering, architectural, and popular journals, first as a guest critic for Casabella in the 1930s, and later as a public voice for engineering as the integration of ethics and aesthetics. Costruire coret-tamente (Constructing Correctly), published in Italy in 1955 and then as Structures in the United States in 1956, summarized his philosophy—it was the designer’s responsibility to consider efficiency and economy above all, but within this remit expressive possibilities and architectural beauty could always be found—in its very title. He enjoyed a late career as a professor, teaching structural design to architects at the University of Rome, Tor Sapienza, from 1945 to 1961, and in 1961 he delivered the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures in Poetry at Harvard, refining his philosophy and linking his own work to “technically correct” and aesthetically satisfying work from the past—the Gothic in particular. Published in 1965 as Aesthetics and Technology in Building, these lectures codified the thinking that had coalesced through over forty years of practice in both design and construction.

Nervi’s upbringing, education, and early experiences are inseparable from his later career. Indeed, they prepared him for the integrated approach that marked his greatest work. Born in northern Italy in 1891 to a family headed by a postal official, Nervi had an itinerant childhood, living for a time in Savona. The family moved on to Ancona, a port town on the Adriatic graced by a domed Romanesque cathedral. There Nervi attended a secondary school run by the Piarists, a Catholic order devoted to educating the poor by integrating them with middle-class children. As the son of a government clerk, Nervi would have gained admission in the latter category, suggesting a conscious choice by devout and socially aware parents. The Piarists professed a disciplined pedagogy similar to the Jesuits, and the ascetic surroundings, classmates from diverse economic strata, and challenging classwork in Ancona undoubtedly influenced the young Nervi. Rigor in thought and discipline in economy accompanied him throughout his life. While he would later play down his religious beliefs, Nervi professed to being spiritual in a way that reflected northern Italy’s reticent character and Piarist humility.

Fascinated by aircraft throughout his youth and having shown a gift for mathematics and science, Nervi left Ancona for university studies at Bologna, and it was there that his approach to engineering was forged. As Micaela Antonucci has shown, Bolognese culture in the 1910s was pulled between tradition and progress in engineering and the arts, creating a vibrant but charged atmosphere.3 Among other figures, the Futurist artist-architect Antonio Sant’Elia taught at the city’s Accademia di Belle Arti, but the conservative atmosphere that permeated the Scuola di Applicazione per Ingegneri di Bologna, where Nervi studied, would have tempered such influences. As its name suggests, the school adopted a professional approach. While in touch with contemporary developments, it balanced theory with real-world experience from teachers who were engaged in construction and design.

Those industries were in the midst of important changes in the first decades of the twentieth century that brought new materials and calculation techniques. Most important was concrete’s emergence as a viable alternative to steel and masonry. Beginning with experiments in Britain and France in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, developments in concrete technology transformed rough, rammed-earth and mortar techniques into a new construction typology. The fortuitous development of iron in parallel with concrete soon led to hybrids. Concrete itself relies on the chemical adhesion of cured cement to hold sand and stone aggregates within a fixed matrix; this works well in compression, but such adhesion is unreliable in tension. Reinforcing tensile or bending elements with iron bars gives concrete much greater strength while adding little to its cost. Reinforced concrete construction gained traction in domestic building in France by the 1850s, but it remained a crude material, its reinforcement more akin to tie rods than to monolithic reinforcement. Its application in houses, theaters, and churches in France through the 1870s proved its durability, strength, and economy compared to iron and other emergent forms of construction. More innovative reinforced concrete emerged in the work of Joseph Monier (1823–1906) in France and British émigré Ernest Ransome (1852–1917) in the western United States. The more important development for Italy—and for Nervi in particular—came in the 1890s with French constructeur François Hennebique’s (1842–1921) patented system, which he licensed to established contractors throughout Europe over the next decades. The Hennebique system featured numerous technical improvements over the hodgepodge of systems available throughout the continent. More importantly, as Peter Collins notes, its license came with a consulting arrangement with Hennebique himself, and a publicity machine that broadcast the material’s revolutionary achievements and potential.4

By the time Nervi arrived at Bologna, the Hennebique system was well-known but still revolutionary. Hennebique’s contributions to the 1900 Paris Exhibition placed the material and his system on the world stage, in particular a curvilinear staircase in the Petit Palais that offered evidence of concrete’s potential for plastic form and its deployment in the framed floors of the exhibition’s enormous main buildings and temporary structures that emphasized its economy.5 Contractors built more than fifteen hundred projects on the Hennebique system every year by the turn of the century. Steel remained prevalent in the United States, even as fires in Philadelphia and Baltimore underlined its vulnerability and further proved concrete’s inherent resistance to heat and flame. Southern Europe—lacking necessary natural resources and thus a native steel industry—took to the new material quickly. The low cost and ready availability of concrete’s ingredients, in particular limestone and aggregates, made it uniquely suited for Italy.

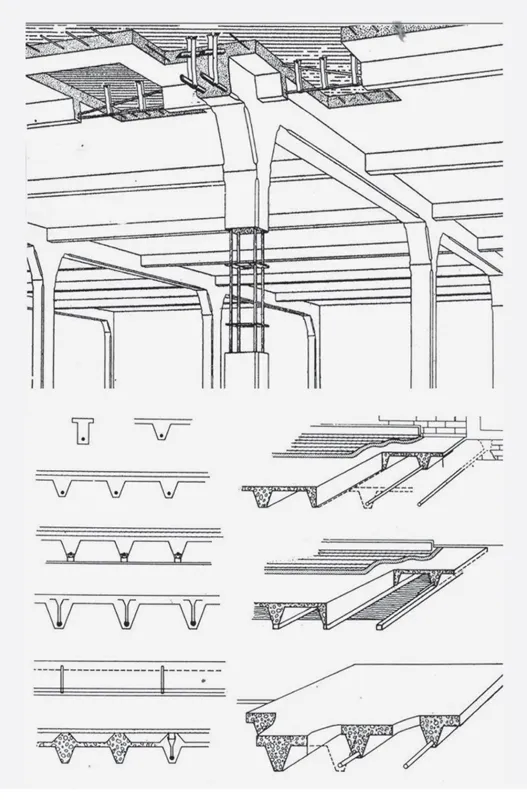

FIGURE 1.2. The Hennebique system (1890s)

Concrete was not only an improvement in economy, it was...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- CHAPTER 1. Background

- CHAPTER 2. “Repetition of Identical Sections”: Structural Precasting

- CHAPTER 3. Precast Ferro-Cement and “Slender Structures”

- CHAPTER 4. “The Harmonious Interplay of Ribs”: Ferro-Cement as Tiling Formwork

- CHAPTER 5. “Lines Easily Realized”: Piers of Varying Sections

- CHAPTER 6. Skyscrapers

- CHAPTER 7. The Late Projects

- CHAPTER 8. Connecting the Two Cultures of Building

- CHAPTER 9. Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index