- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

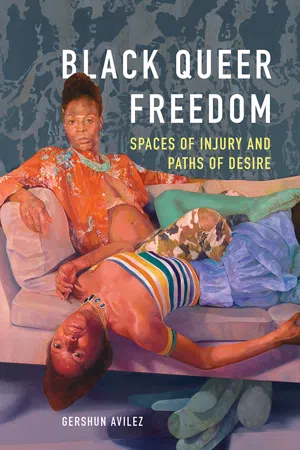

Whether engaged in same-sex desire or gender nonconformity, black queer individuals live with being perceived as a threat while simultaneously being subjected to the threat of physical, psychological, and socioeconomical injury. Attending to and challenging threats has become a defining element in queer black artists' work throughout the black diaspora. GerShun Avilez analyzes the work of diasporic artists who, denied government protections, have used art to create spaces for justice. He first focuses on how the state seeks to inhibit the movement of black queer bodies through public spaces, whether on the street or across borders. From there, he pivots to institutional spaces—specifically prisons and hospitals—and the ways such places seek to expose queer bodies in order to control them. Throughout, he reveals how desire and art open routes to black queer freedom when policy, the law, racism, and homophobia threaten physical safety, civil rights, and social mobility.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Black Queer Freedom by GerShun Avilez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & LGBT Literaturkritik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

THREATENED BODIES IN MOTION

1.MOVEMENT IN BLACK

Queer Bodies and the Desire for Spatial Justice

The American Streets resembled nothing so much as one vast, howling, unprecedented orphanage.

—James Baldwin, No Name in the Street

James Baldwin’s autobiographical book-length essay No Name in the Street (1972) is an extended consideration of the social and political scene of the United States in the late 1960s.1 In it, Baldwin describes the civil rights struggle as the “American crisis” (475), and he goes on to explore the set of problems facing the realization of Black freedom. The most significant obstacle to this freedom is the circulating idea that African Americans “must know their place” (463). Baldwin means this idea figuratively in terms of social station, but he also means it literally as the practices of racial segregation and housing-market redlining illustrate. The challenge facing Black freedom is a problem of spatial restriction and alienation, and this idea gets registered in his comparison of the American streets to a “vast, howling, unprecedented orphanage” (468). The streets resemble an orphanage in terms of the placement of African Americans in the social realm. The metaphor conveys the idea of homelessness and describes the lack of freedom of movement. The street is figured as a space of enclosure (an orphanage) instead of mobility. Orphans have few protections, are perpetually controlled, have compromised agency, and are often figured as undesirable in the social imaginary. Through this powerful metaphor, Baldwin characterizes African American existence at the beginning of the post–civil rights era in terms of the absence of connections and resources and in terms of spatial restriction.

The use of the framework of space—and geography, in particular—to discuss African American life is not particular to Baldwin; it is a frequent element within Black literary culture.2 However, a specific triangulation of civil rights, space, and the queer body emerges in the work of Black gay and lesbian writers, such as Baldwin, in the post–civil rights era. The experience of Black queer life reveals a multivalent spatial restriction that highlights the boundaries of civil rights advancement and questions the progress narrative most often associated with the US civil rights movement. This chapter presents the argument that Black gay and lesbian artists take up the question of spatial justice in their works because they recognize the particular social insecurity for those who sit at the intersection of racial and sexual minority existence. The desire for spatial justice reflects the goal of circumventing the threat of injury in the social world. Black gay and lesbian artists contend with the spatialized inequality that eludes legislation and policy changes and that comes to define Black queer life, in general.

By spatial justice, I refer to the artistic, philosophical, and activist project of describing the ongoing denial of freedom of movement for minorities that is paired with the claims of the right of mobility and the right to occupy public space. Spatial justice consists of a minority asserting a proprietary right to the public realm and the public record, which legislation and majority public opinion have contentiously defined. It is a framework that expresses desires to occupy and to move through the social world autonomously, capacities that have been historically denied because of race, gender, and/or sexual identity. In making this argument about Black queer artists and spatial justice, this chapter builds on the critical contributions of geographers and spatial theorists, especially, Edward Soja and Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos. However, my work departs from these thinkers in three ways: the focus on the contributions that artistic productions make to spatial theory; the attention to how historical knowledge shapes spatial understanding; and the emphasis on the queer implications of spatial justice. Finding that urban streets are dangerous for racial and sexual populations even in the context of shifts in policies, Black queer artists imagine spatial justice as the antidote for historic and ongoing social restriction. An artistic focus on the queer body recalibrates theoretical approaches to space.

The poetry of the Black lesbian cultural producers Cheryl Clarke and Pat Parker is integral to establishing this notion of spatial justice because both articulate post–civil rights era African American identity as a manifestation of a spatialized civic dilemma, and both situate the Black queer body as the mechanism for asserting this idea. To set up the analysis of the work of Clarke and Parker, the chapter explores the spatial implications of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and how this piece of legislation fails to transform the Black experience of spatial restriction by looking at the “riots” that occur after the passage of the bill. From there, the chapter offers a theorization of spatial justice and uses Clarke’s poetry to elaborate this conception. Through her poetic mapping of urban spaces, Clarke details the kinds of violence that racial and sexual minorities face and that create feelings of spatial alienation because of being denied access to the social world. Building on Clarke’s work, Parker’s poetry shows how artists not only make claims for public space but also begin to call for a transformation of the public world. This transformation moves beyond a world in which racial identity and sexual preference endanger an individual. Both artists draw attention to how public space is laden with histories of oppression even as these artists seek to attribute new meanings through their assertions of autonomy and desire so that public space, here the space of the street, is always a contested site. This chapter reveals how calls for spatial justice, which derive from ongoing Black spatial restriction, result in artistic projects concerned with queer self- and world-making even in the context of layered conflict.

The consideration of these ideas begins by focusing on the framework and cultural ramifications of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 because it is seen as one of the most important pieces of US civil rights legislation of the twentieth century and because it emphasizes the reconfiguration of public space as the proper means for undoing legacies of discrimination. This omnibus act consolidates and provides more enforcement power to two previous legislative iterations: the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and the Civil Rights Act of 1960. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 is made up of eleven major titles (or sections). Important titles in the 1964 version mandate: banning voter-registration requirements (title 1), prohibiting the denial of access in public facilities (title 3), prohibiting discrimination by government agencies that receive federal funding (title 6), and prohibiting employment discrimination (title 7). Here, attention is given to title 2, which outlaws discrimination in public accommodations engaged in interstate commerce. This component of the law promotes equity in terms of access to the social world. It seeks to guarantee freedom of movement through public space—as the grounding concept of interstate commerce intimates. The legislators chose to focus on the commerce clause of the US Constitution in creating the document, meaning that issues of mobility lie at the heart of this rendering of legislative change. First considered are the spatial implications of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, followed by two historical urban incidents that demonstrate the limits of the act’s impact, all of which sets up the desire for spatial justice.

Mobility in several registers is central to the legislative logic of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Legislators crafted the act around the commerce clause in article 1, section 8, of the Constitution to ban discrimination in public places: “The Congress shall have Power […] to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes; […] To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers.”3 Interstate commerce and citizen mobility serve as the reasoning for arguing for federal intervention in racial discrimination. In an August 1963 statement to the US House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy explains,

Arbitrary and unjust discrimination in places of public accommodation insults and inconveniences the individuals affected, inhibits the mobility of our citizens, and artificially burdens the free flow of commerce. […] The effects of discrimination in public establishments are not limited to the embarrassment and frustration suffered by the individuals who are its most immediate victims. Our whole economy suffers. When large retail stores or places of amusement, whose goods have been obtained through interstate commerce, artificially restrict the market to which these goods are offered, the Nation’s business is impaired. […] Discrimination in public accommodations not only contradicts our basic concepts of liberty and equality, but such discrimination interferes with interstate commerce and the development of unobstructed national market.4

Discrimination is not about individual frustrations or the dilemmas of one particular group in the nation; rather, it threatens the stability of the US social world. Kennedy and his colleagues situate racial discrimination as a challenge to an ostensibly healthy capitalist economy. The legal reasoning makes the freedom of movement of people (and goods) crucial to the structure of civil rights discourse. The act has woven into its structure a valuation of unrestrained mobility within and throughout, which gets connected to national vigor and the definition of full citizenship. The desire for equal access to public spaces that Kennedy describes lies at the heart of civil rights activists’ strategizing.5

As much as interstate commerce is about transactions and the world of publicly funded business affairs, it also concerns the control of movement between localities. The attention to interstate commerce pertains to the legislation of public space and the determining of what counts as public space. This move expands the reach of federal state power, but it also allows a freedom of civic movement, as Kennedy’s comments indicate. The dismantling of historic spatial restrictions (i.e., segregationist social systems) in terms of literal and figurative social boundaries has meant that questions of mobility, space, and access have become critical elements of civil rights discussions even in the wake of significant legislation. Title 2 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the act in general attempt to reconfigure the social realm. Dismantling segregation involves restructuring the social world. It is not just about a change in the legal landscape; instead, it evidences an attempt to reimagine how we conceptualize social space to undo the foundations of a nationwide geography of restriction. The reproduction of public space is the goal here. Such reimagining was and continues to be the precise terrain of civil rights. Critics who talk about the production of space do not generally do so in terms of shifts in civil rights discourse.6 Thinking about civil rights necessarily means thinking about space.

Although this monumental act concerns ensuring access to public spaces of commerce (publicly funded places), one wonders, What happens outside of and in between those protected sites of commerce?7 What happens in the streets? Streets, especially urban streets, prove to be highly dangerous and expose the vulnerability of the Black body even after the advent of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.8 Two significant incidents that occurred soon after the passage of this piece of legislation demonstrate this point: the Harlem–Bedford-Stuyvesant uprising in July 1964 and the Newark uprising in July 1967.9 The Harlem uprising began on July 16, two weeks after the Civil Rights Act was enacted. On Thursday, July 16, James Powell, a fifteen-year-old summer-school student and resident of the Bronx Soundview public housing project, was shot by Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan, who was out of uniform and not on duty, in the Manhattan Upper East Side neighborhood of Yorkville. That morning, building superintendent Patrick Lynch was hosing down the sidewalk in front of the buildings he managed and noticed that a number of young Black students from the nearby junior high school were hanging out on the stoop or front steps of one of the buildings. This lounging had been happening regularly, and the superintendent had grown frustrated with the students’ occupation of these areas and their general presence on his block. Lynch sprayed the students with his hose. The young men claimed that it was done with malice and that Lynch also uttered, “Dirty Niggers, I will wash you clean.”10 Lynch insisted that it was a mere accident. Either way, the situation escalated. This action—even if accidental—carried with it racialized meaning, given the frequency of police turning hoses on Black people as a form of crowd control and to exercise power over agitators during the 1960s. In response to being soaked forcefully, the boys threw bottles and garbage-can lids at Lynch, attracting the attention of other boys nearby, including Powell. Joining in the fracas, Powell ran inside the building followed by an agitated Lynch. Gilligan was nearby and rushed to the scene to get matters under control. There is much disagreement on the exact course of events among those present that day, but Gilligan shot Powell three times as Powell exited the building. He did not get help in time and died soon thereafter. The death led to public accusations of police brutality, excessive force, and discrimination, as well as a picketing of the school. After Powell’s funeral in Harlem, which was held two days later, many of the attendees decided to march to the Twenty-Eighth Precinct police headquarters on Seventh Avenue. A confrontation with police ensued, with gunfire coming from the precinct forces. Four days of picketing, ransacking stores, and assembling resulted, which spread from Harlem to Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn. Increased police presence and rain ultimately quelled the action of the mourners and protestors.11

The uprising in Newark came three years later, in 1967, after social upheavals in other cities, such as Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Chicago, Illinois; Jersey City, New Jersey; and Rochester, New York; and after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Once again, the setting is a warm summer day—the evening instead of the morning. Black taxi driver John Smith was pulled over by two Newark police officers, Vino Pontrelli and Oscar De Simone. It is not clear why Smith was stopped or why the situation became violent. Pontrelli and De Simone claimed that Smith had tailed them, turned the wrong way on a street, and was belligerent when pulled over. Smith claimed that the police car was double-parked, so he signaled and went around it; he was pulled over, berated, and then punched by the officers. In any event, Smith was pulled from the car, beaten, and taken into custody for resisting arrest and assaulting an officer. Upon arrival at the precinct, the police officers were witnessed dragging a seemingly unconscious Smith into the building. Other taxi drivers circulated news of the arrest and transported people to a demonstration—some feared that Smith had been beaten to death. People rushed to the precinct station. As in Harlem, police stormed out of the precinct to control the demonstration, which lead to a violent confrontation. An overwhelming uprising broke out in the Central Ward of Newark that went on for five days: “More than 1,100 sustained injuries; approximately 1,400 were arrested, some 350 arsons damaged private and public buildings; millions of dollars of merchandise was destroyed or stolen; and law enforcement expended 13,326 rounds of ammunition.”12 All off-duty police were called to action, and the governor later called out the state troopers as well as the National Guard. A front-page New York Times article from the next day, July 13, reports, “Bands of Negroes went through a heavily Negro neighborhood in South Newark last night and early today smashing windows and looting stores.” The assembled are also described as “rampaging gangs” in the article. As this piece demonstrates, the public narrative about the event tended to characterize the protestors in negative ways. The violence and destruction were monumental. Later that year New Jersey governor Richard J. Hughes authorized a report to figure out what had happened and how to address the attendant social problems: The New Jersey Governor’s Commission Report of Action (1968). The report offered a more nuanced picture of the protestors and the conditions in which they lived. It opens with the image of a young Black boy peering apprehensively outside his door.13 The image suggests a fear of going outside, that dangers lurk on the street. The commissioners that produced the report chronicle—even if inadvertently—a lack of freedom of movement in the public world. This idea frames the study of racial conflict in urban space.

These two events in relatively adjacent urban areas concern racial tension, excessive police violence, housing segregation, the lack of economic resources, and the monitoring of the boundaries of communities. What unites these incidents are Black frustrations with spatial matters and embodied movement. The inciting event for the occurrences in Harlem has to do with the lack of access to public space. Lynch is upset about the youth on the stoop and about the fact that these boys from a different neighborhood inhabit the block and his street. Gilligan’s gunshot is an unfortunate and fatal extension of Lynch’s space-denying water hose. Both are acts of interruption. The tumult in Newark results from the police officer’s willful interruption of Smith’s movement along a street. In one instance, Black individuals are denied access to space; in the other, an individual’s movement is impeded. Both events and the turmoil that resulted illustrate spatial denial and restriction.14

As the New Jersey governor’s Report of Action indicates, much time was spent and much ink was used trying to make sense of why days-long confrontations occurred. In response to this recurring questioning that happened in city halls and classrooms and on street corners, Black gay civil rights activist and writer Bayard Rustin opines:

But why, asks white America, do the Negroes riot now—not when conditions are at their worse but when they seem to be improving? Why now, after all of the civil rights and antipoverty legislation? There are two ans...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Freedom in Restriction

- Part One. Threatened Bodies in Motion

- Part Two. Bodies in Spaces of Injury

- Conclusion: Lives of Constraint, Paths to Freedom

- Notes

- Index

- Back Cover