eBook - ePub

English in Print from Caxton to Shakespeare to Milton

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

English in Print from Caxton to Shakespeare to Milton

About this book

English in Print from Caxton to Shakespeare to Milton examines the history of early English books, exploring the concept of putting the English language into print with close study of the texts, the formats, the audiences, and the functions of English books. Lavishly illustrated with more than 130 full-color images of stunning rare books, this volume investigates a full range of issues regarding the dissemination of English language and culture through printed works, including the standardization of typography, grammar, and spelling; the appearance of popular literature; and the development of school grammars and dictionaries. Valerie Hotchkiss and Fred C. Robinson provide engaging descriptions of more than a hundred early English books drawn from the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and the Elizabethan Club of Yale University. The study nearly mirrors the chronological coverage of Pollard and Redgrave's famous Short-Title Catalogue (1475-1640), beginning with William Caxton, England's first printer, and ending with John Milton, the English language's most eloquent defender of the freedom of the press in his Areopagitica of 1644. William Shakespeare, neither a printer nor a writer much concerned with publishing his own plays, nonetheless deserves his central place in this study because Shakespeare imprints, and Renaissance drama in general, provide a fascinating window on the world of English printing in the period between Caxton and Milton.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access English in Print from Caxton to Shakespeare to Milton by Valerie Hotchkiss,Fred C. Robinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Illinois PressYear

2010Print ISBN

9780252075537, 9780252033469eBook ISBN

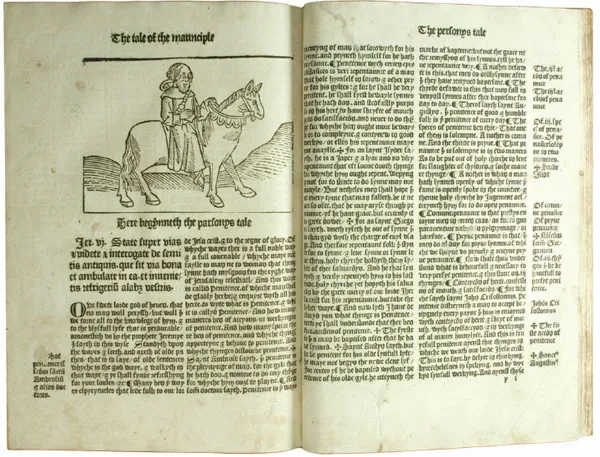

9780252091537CATALOG OF THE EXHIBITION

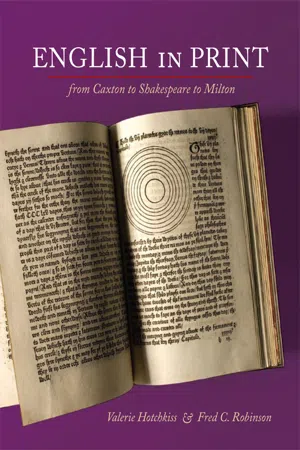

1.1, fol. 33v

1 EARLY ENGLISH PRINTING

1.1 | The Brut. Manuscript, England, c. 1450. Matheson 1998, 81, 120. Shelfmark: UIUC Pre-1650 ms 116. |

1.2 | Chronicles of England. [London: William de Machlinia, 1486?] BMC xi, 261; ESTC S121384; Goff C-480; GW 6673; ISTC ic00480000; STC 9993. Shelfmark: UIUC Incunabula 942 C468 1486. |

When printed books became available, scriptoria did not close their doors. On the contrary, manuscripts went on being produced — and sometimes preferred by their owners — throughout the fifteenth century. These two copies of the same text, one a manuscript, the other an early printed edition, exemplify the many continuities between early printed books and their manuscript forebears.

Both books present the text of the Chronicles of England, also known as The Brut. The Brut is simple to describe — it is a history of England beginning with its legendary founder, Brutus — but its textual history is complex. The earliest versions, the Anglo-French Roman de Brut by Wace in 1155 and the Middle English poetic Brut by Layamon (early thirteenth century), stem from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s (d. 1154) Historia regum Britanniae. Thereafter, the most popular version is the fourteenth-century Middle English prose Brut, an anonymous text that survives in some 181 manuscripts. Not surprisingly, the text varies somewhat depending on where, when, and by whom the chronicle was written down or printed. There are Bruts with pro-Lancastrian biases and Bruts with pro-York biases; there are Bruts in Anglo-Norman, Welsh, and Latin, as well as the more common text in English. The history is sometimes updated to the time of its production, resulting in a different terminus ad quem for various manuscript groups or editions. Early modern historians of England such as Edward Hall (1497–1547) and Raphael Holinshed (c. 1525–80) incorporated The Brut into their histories, and it continues to serve as a source for historians.

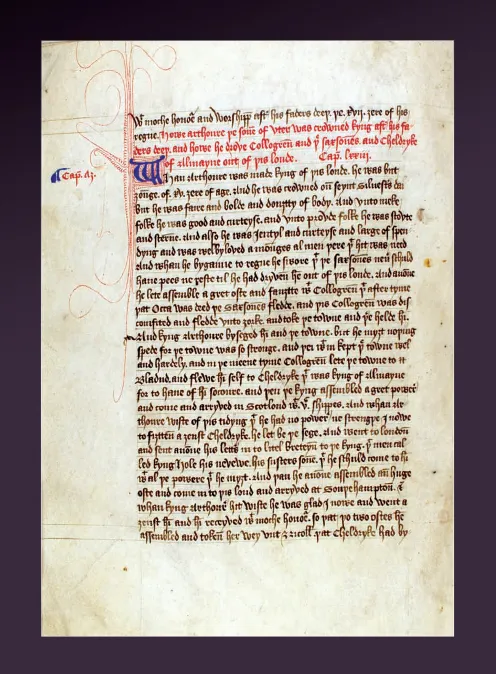

1.2, fol. E5v

England’s first printer, William Caxton, published the editio princeps of The Brut in 1480; his version brings the historical account up to the year 1461. Caxton published a second edition in 1482. Thereafter, editions appeared in quick succession from the presses of the St. Albans Printer (c. 1485), William de Machlinia (1486), Wynkyn de Worde (1497), and even from Gerard de Leew in Holland (1493).

William de Machlinia (fl. 1482–90), the printer of the 1486 edition shown here, may have learned his trade from John Lettou, the earliest printer working in the City of London. Lettou was probably not English (his name means “Lithuanian” in Middle English), and De Machlinia was probably from Mechlin in the Low Countries. They collaborated on publishing law books in French and Latin. After 1483, De Machlinia began to print on his own, adding English books to his output and thereby becoming the first printer to produce an English book in the City of London. (Caxton was at Westminster, just outside the City of London.)

Although De Machlinia clearly used Caxton’s first edition as his source text, it is nonetheless instructive to compare a manuscript and an incunable of the same text. Early printers imitated the handwriting of medieval scribes with their typefaces and adopted manuscript conventions in designing page layouts. The same passage in the manuscript and the 1486 imprint reveals the similarities in book design, despite some textual differences (the manuscript offering more detail on the coronation and character of King Arthur in this case).

The printed edition belonged to the printer and designer William Morris (1834–96),who found models for his own designs in several magnificent books from the incunabular age.

Literature: Carlson 1993, 123–41; Clair 1965, 31–34; König 1987; Matheson 1998, 1–56.

1.3 | Marcus Tullius Cicero. De Senectute. De amicitia. With the De vera nobilitate of Buonaccorso da Montemagno the Younger. [Westminster: William Caxton, 12 August 1481.] BMC xi, 119; ESTC S106523; Goff C-627; GW 6992; ISTC ic00627000; STC 5293. Shelfmark: UIUC Incunabula 871 C7 ob.EW. |

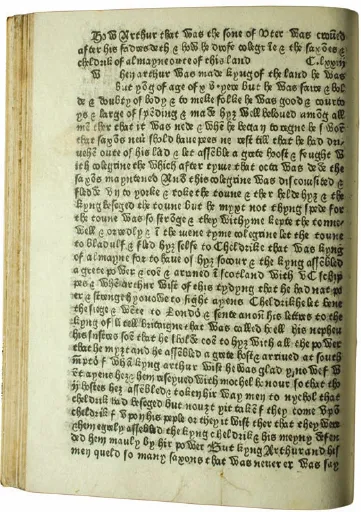

Printing presses operated in nearly seventy towns on the Continent before William Caxton established the first one in England in 1476, a quarter of a century after Gutenberg. Printing came late to England, and England’s first printer came late in life to printing. After a successful career as a merchant, Caxton learned to print in his mid-fifties, probably in Cologne. His motivation may have resulted from his experiences as a merchant. As a member of the Mercers’ Guild, he traded in textiles, including not only fabric, but also skins and, by extension, manuscripts, which were written on treated animal skins. According to the epilogue of his first book, The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye (printed in Bruges, 1473 / 74), he learned the art of printing in order to supply multiple copies of a manuscript to “divers gentlemen.”

Soon, Caxton became much more than a printer and purveyor of books. He translated popular French literature for his English public, produced English versions of classical texts, and edited and printed the works of Chaucer, Lydgate, Gower, and Malory, among others. England continued to import books from the Continent, of course, but Caxton created a market for English books.

Caxton dedicated these three “bokes of grete wisedom and auctoryte” to King Edward IV. In the prologues, he says that Sir John Fastolf (1380–1459) commissioned the translation of Cicero’s De Senectute (On Old Age) and that John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester (1427–70), translated the works on friendship and nobility (De amicitia and De vera nobilitate).1 Caxton printed Cicero’s works on old age and friendship together, he says, “by cause ther can not be annexed to olde age a bettir thynge than good and very frendship” (2 d4v).

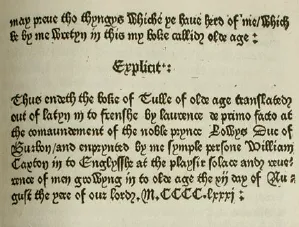

1.3, fol. I3r

1.4, fol. X6v–Y1r

Ultimately, Caxton’s goal transcended that of the businessman interested in mass producing a desired commodity. Yet he does not conform to the mold of the scholar-printer that emerged among the second-generation continental printers either. Though he calls himself a “symple persone” in the colophon of this book, Caxton was a cultural activist for English literature, who created an audience for leisure reading in the vernacular. As Nicolas Barker put it, “No other left his mark so strongly, both on the appearance of print and on taste in reading matter, as Caxton did in England.”

Literature: Barker 1976, 133; Blake 1973b, 120–25; Corsten 1976; odnb (“Caxton, William” by N. F. Blake); Painter 1976, 111–16.

1.4 | Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1340–1400). The boke of Chaucer named Caunterbury tales. Westminster: Wynkyn de Worde, 1498. BMC xi, 214; ESTC S108866; Goff C-434; GW 6588; ISTC ic00434000; STC 5085. Shelfmark: UIUC Incunabula Q. 821 C39c 1498. |

1.5 | Ranulf Higden (d. 1364). The descrypcyon of Englonde. Westminster: Wynkyn de Worde, 1498. BMC xi, 214; ESTC S116801; Goff C-482; GW 6675; ISTC ic00482000; STC 13440b. Shelfmark: UIUC Incunabula 909 h53p:Et 1498. |

After Caxton’s death, Wynkyn de Worde (d. 1534 / 35) assumed control over his press, a natural development for him since he had worked for C...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Catalog of the Exhibition