eBook - ePub

Hildegard of Bingen

About this book

A Renaissance woman long before the Renaissance, the visionary Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) corresponded with Europe's elite, founded and led a noted women's religious community, and wrote on topics ranging from theology to natural history. Yet we know her best as Western music's most accomplished early composer, responsible for a wealth of musical creations for her fellow monastics.

Honey Meconi draws on her own experience as a scholar and performer of Hildegard's music to explore the life and work of this foundational figure. Combining historical detail with musical analysis, Meconi delves into Hildegard's mastery of plainchant, her innovative musical drama, and her voluminous writings. Hildegard's distinctive musical style still excites modern listeners through wide-ranging, sinuous melodies set to her own evocative poetry. Together with her passionate religious texts, her music reveals a holistic understanding of the medieval world still relevant to today's readers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hildegard of Bingen by Honey Meconi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medien & darstellende Kunst & Musikbiographien. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1Before Rupertsberg

Composer. Poet. Performer. Dramatist. Visionary. Prophet. Theologian. Exegete. Cosmologist. Spiritual leader. Preacher. Exorcist. Philosopher. Founder. Correspondent. Political advisor. Monastic troubleshooter. Hagiographer. Naturalist. Medical writer. Linguist. Noblewoman. Nun. Magistra. Teacher. Healer. Autobiographer. All of these roles describe Hildegard of Bingen.

Many know Hildegard today foremost or even exclusively as a composer, and her achievements in this area are indeed noteworthy: the most prolific composer of plainchant; one of the earliest—male or female—that we know by name; creator of the first musical “morality play” (and the only one for whom we have a named composer); and composer of seventy-seven songs, all but one set to her own idiosyncratic poetry in a distinctive and glorious musical style. But just as her music, all plainchant, distinguishes her from the many other feisty and creative spiritual women of the twelfth century, so, too, do her nonmusical accomplishments separate her from virtually all other major composers (whether of the Middle Ages or later times), few of whom are known for anything but composition, and almost none of whom are of equal significance in another field.1 Yet during her lifetime and until very recently it was not Hildegard’s music that led to her fame; rather, it was her spirituality. Indeed, Hildegard’s was a holistic life, and her music can only be understood as one facet of a creativity that mirrored and was generated by her religious beliefs.

Simply put, Hildegard was a visionary. She literally “saw things” that she claimed were revealed to her by God, and in her early forties—she lived to be eighty-one—she began writing these things down. Over a productive span of almost forty years she generated three major theological works: Scivias (Know the Ways), Liber vite meritorum (Book of Life’s Merits), and Liber divinorum operum (Book of Divine Works); two works of hagiography (lives of St. Rupert and St. Disibod); several smaller theological writings (a commentary on the Benedictine Rule, a commentary on the Athanasian Creed, a series of homilies on the Gospels, and a set of answers to thirty-eight questions sent to her by Cistercian monks); an extensive correspondence of almost four hundred letters and replies, the list of whose recipients reads like a who’s who of twelfth-century Europe; a volume of natural history (Physica); the medical treatise Cause et cure (Causes and Cures); an invented language (Lingua ignota, Unknown Language) and accompanying alphabet (Litterae ignotae, Unknown Letters); perhaps works of art (sketches for the illustrations that accompany one manuscript of Scivias); an exorcism ritual; an autobiography; and, of course, her musical play, Ordo virtutum (usually translated as “The Play of the Virtues”), and her songs, commonly known as the Symphonia armonie celestium revelationum (Symphony of the Harmony of the Celestial Revelations).2 Almost all of these works are included in a massive manuscript begun toward the end of her life known as the Riesencodex (Giant Codex), and all result from a holistic concept of creation.

We know of Hildegard’s works through the Riesencodex and other manuscripts, and we also—unusually for the Middle Ages—have a great deal of information about her life. Biographical material is sprinkled throughout her correspondence and appears as well in the prefaces to some of her works. And since Hildegard achieved a considerable amount of fame during her lifetime, others wrote about her both while she was still alive and for some time after her death. Close to the end of her life, her secretary Gottfried of Disibodenberg began a vita, the standard biographical work for saints and those perceived as saintly. Finished after his (and Hildegard’s) death by the monk Theoderic of Echternach, the Vita Sanctae Hildegardis (hereafter Vita) included autobiographical portions by Hildegard herself.3 A second vita was begun but never finished by Hildegard’s last secretary, Guibert of Gembloux (sometimes referred to as Wibert), who also left a set of revisions for the Gottfried/Theoderic Vita, as well as a series of letters to various correspondents that contain additional material on Hildegard. Eight readings generated after her death and used on her feast day provide another source of information, as does the early thirteenth-century Acta inquisitionis de virtutibus et miraculis S. Hildegardis (Acts of the Inquiry into the Virtues and Miracles of Hildegard), a document drawn up in connection with Hildegard’s canonization proceedings.

In contrast to almost all other medieval composers, then, we have a vast amount of information about Hildegard’s life. Unfortunately, large gaps still remain, few dates are firm, and many contradictions mar the material that survives. Just how accurate all these sources are is another very big question. As a result, the story of her life as we know it today is both intensely frustrating (how much is true?) and extraordinarily thrilling.

Beginnings

Hildegard was the tenth child of noble parents, Mechtild and Hildebert of Bermersheim near Alzey in the diocese of Mainz. Although various later twelfth-century documents offer a birth year of 1100, perhaps chosen for its symbolism, all three of Hildegard’s major theological writings, which she is careful to date, point to an earlier birth year. In the preface to her first book, Scivias, Hildegard says that she was in her forty-third year in 1141, precisely stating her age as forty-two years and seven months. This could generate a birth date anywhere between June 1098 and May 1099. In the preface to Liber vite meritorum, however, she says both that she was sixty in 1158 and that it was the sixty-first year of her life, while in the preface to Liber divinorum operum she gives the year as 1163 and says that she is sixty-five. Both thus fix her birth date firmly in 1098. Finally, the Vita indicates that when Hildegard passed away on September 17, 1179, she was in the “82nd year of her life” and therefore eighty-one years old.4 Her birthday was thus somewhere between June and mid-September of 1098.

Hildegard began having visions at an early age—the Vita puts these as far back as when she first learned to talk—and spoke of them artlessly until her fifteenth year, only gradually realizing that others did not see as she did.5 Once she became aware of how different she was, she mostly kept things to herself until she was more than forty years old,6 even though the visions continued. Only one of her earliest visions is known: according to the canonization report, the five-year-old Hildegard was able to tell the color and markings of an unborn calf.7 In terms of her visions, Hildegard insisted throughout her life that she was a “poor little creature” and a “weak woman” whom God had chosen as a vessel for his message; it was never Hildegard speaking, she claimed, but rather the Holy Spirit acting through her.8

The vision of the unborn calf supposedly prompted her parents to consider what to do with their unusual daughter. In addition to seeing visions, Hildegard was a sickly child who would ultimately endure poor health for extended periods in her adult life, typically at moments of great stress. These two factors boded ill for the marriage market, and some have speculated that her parents had run out of money for a dowry for their last child. In any event, ultimately she was “offered to God.” Guibert of Gembloux describes this act as a tithe on her parents’ part,9 but this seems unlikely given that three of her siblings were already dedicated to the Church. Moreover, the Church frequently served as a refuge for the frail offspring of noble families in the Middle Ages.

Like so much of Hildegard’s early life, exactly when this “offering” occurred and what it consisted of is open to interpretation. Although the Vita says it took place in her eighth year (1105/1106), it was not until 1112—specifically on November 1, the Feast of All Saints—that Hildegard made a formal pact with the Church. She did not do this alone, but rather in the company of two other women, one of whom was to be her teacher and mentor for the next twenty-four years.

This woman was Jutta of Sponheim, a pious young woman a mere six years older than Hildegard. Member of a noble family somewhat more distinguished than Hildegard’s, Jutta fell seriously ill at the age of twelve. Upon recovery she set about fulfilling a vow to pursue a holy life. Acting first as a disciple to a holy widow named Uda of Göllheim, she next planned a pilgrimage, but her brother dissuaded her from pursuing this idea. Instead, she opted for something much more dramatic: enclosure within the Benedictine monastery of Disibodenberg. And she took Hildegard with her.

Enclosure

Exactly when Hildegard met Jutta is unknown. One theory is that she came to Jutta in her eighth year, the time the Vita says Hildegard was offered to God, and that Hildegard lived at Sponheim with Jutta as the latter’s own disciple. If so, this life was ultimately insufficient for either Hildegard or Jutta, and a more drastic step was taken. Hildegard, Jutta, and Jutta’s niece (acting as their servant, and also named Jutta) chose Disibodenberg as their future home.

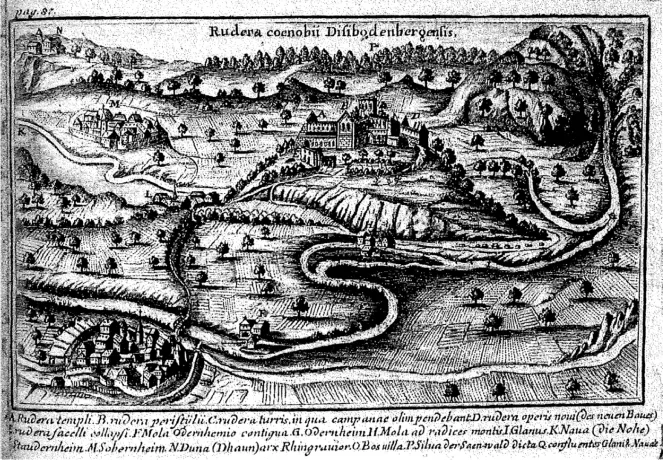

Disibodenberg—surviving today only in ruins, as seen in figure 1—was a new Benedictine community, founded on the site of an earlier dwelling whose Augustinian canons had been displaced in favor of the monks. Construction of the new monastery began on June 30, 1108,10 with monks from the Mainz abbey of St. Jacob living at the site from at least the previous year. The building campaign included an impressively large church whose first altar was dedicated in 1130 and whose main altar was finally dedicated only in 1143. Most of Hildegard’s life at Disibodenberg—where she would dwell longer than anywhere else—was thus lived to the accompaniment of the noise of construction. The monastery proper was restricted to a relatively contained territory at the top of a steep hill, though its property ownership—a major source of income—eventually spread over a wide area. At some point Jutta’s own family gave property to the monastery as well. The monastery’s site accords with the older Benedictine preference to build on mountaintops (“contemplative ascent to God”) versus the Cistercian practice of gravitation to “isolated valleys, symbolizing humility.”11

Figure 1. Disibodenberg (“Rudera coenobii Disibodenbergensis”) from Georg Christian Joannis, Tabularum litterarumque veterum usque hoc nondum editarum Spicilegium (Frankfurt am Main: J. M. a Sande, 1724), 87.

In the early twelfth century, double monasteries—a community of monks joined to a community of nuns—existed, but Disibodenberg did not begin as one of those. Jutta’s relationship to the community was rather that of holy woman living within the monastery’s walls and thus providing luster and the flavor of greater than usual sanctity to the community; the presence of an anchoress at a male monastery was not uncommon in the Mainz diocese. Jutta also chose the most extreme mode of living, that of strict enclosure, which permitted a single opening through which food could be passed and human waste removed. Thus on November 1, 1112, following a formal ceremony, Hildegard and the two Juttas were literally walled into their living space, with the understanding that they would leave that humble dwelling only upon their death. Hildegard’s monastic profession, to Bishop Otto of Bamberg (later St. Otto), was made at some unspecified time, possibly the same day.12

Guibert describes the situation thus: “And so with psalms and spiritual canticles the three of them were enclosed in the name of the most high Trinity. After the assembly had withdrawn, there they were left in the hand of the Lord. Except for a rather small window through which visitors could speak at certain hours and necessary provisions be passed across, all access was blocked off, not with wood but with stones solidly cemented in.”13

Further discussion of Jutta’s enclosure by Guibert indicates that “in this way, she so provided herself with a haven of seclusion that she would not hinder the monks either by her own presence or by any of the visitors who approached her, or herself be hindered by anyone. On the other hand, far from the clamour of the crowd, she had free access by day and by night to the offices of the monks at their psalmody nearby.”14

Enclosure provided security from physical harm—an eternal danger for women—but that was at most only a subliminal reason for undertaking such a drastic step. The primary impetus was for the better practice of spiritual piety. As Guibert says, “They earnestly inclined themselves to God with prayers and holy meditations, checking the urges of the flesh with constant fasts and vigils.”15 Jutta specifically matched the stereo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Before Rupertsberg

- 2 A New Life

- 3 New Challenges

- 4 New Creations

- 5 Expansion

- 6 After Volmar

- 7 Aftermath

- 8 Hildegard’s Music: An Overview

- 9 Liturgy and Shorter Genres

- 10 Longer Genres

- List of Works

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Selected Discography

- Index