- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Experts often assume that the poor, hungry, rural, and/or precarious need external interventions. They frequently fail to recognize how the same people create politics and knowledge by living and honing their own dynamic visions. How might scholars and teachers working in the Global North ethically participate in producing knowledge in ways that connect across different meanings of struggle, hunger, hope, and the good life?Informed by over twenty years of experiences in India and the United States, Hungry Translations bridges these divides with a fresh approach to academic theorizing. Through in-depth reflections on her collaborations with activists, theatre artists, writers, and students, Richa Nagar discusses the ongoing work of building embodied alliances among those who occupy different locations in predominant hierarchies. She argues that such alliances can sensitively engage difference through a kind of full-bodied immersion and translation that refuses comfortable closures or transparent renderings of meanings. While the shared and unending labor of politics makes perfect translation--or retelling--impossible, hungry translations strive to make our knowledges more humble, more tentative, and more alive to the creativity of struggle.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hungry Translations by Richa Nagar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Experimental Methods in Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Illinois PressYear

2019Print ISBN

9780252084409, 9780252042577eBook ISBN

9780252051418PART ONE

Staging Stories

Learning Moments

As my fingers begin to type these words, I am filled with a sense of deep humility. I recognize that for each one of us who is afforded the means or tools to step in with an authority to make knowledge claims, there are millions of others whose words and knowledges we stand on, but who have been systematically made invisible on the pages and spaces of formal learning—except as objects or subjects who must be researched, represented, discussed, and at times, ‘uplifted’ by the experts. In making a call to end the violence of such erasures, this book asks: Whom do we bring with ourselves onto the page or stage? Whose are the voices we rely on for weaving our stories, but whose tones and accents remain unheard and unacknowledged in our scripts? Who are the people who remain forgotten in our citational practices and for whom the conventional citations of the academy remain meaningless? Can we hope to achieve justice by radically reworking the ways in which these unheard tones, stolen voices, and erased knowledges are rendered through academic practices?

On the opening page of his Politics in Emotion: The Song of Telangana, Himadeep Muppidi reminds us of the art of storytelling, of proverbs and parables that can mend old tears and give birth to new solidarities, of words drunk with the “palm-oil” of stories and songs that can make bodies dance and sing and sway toward new horizons.1 But he has a poignant reminder for us: even as the narrator whose own body migrates, learns, and writes in spaces along the banks of both the Mississippi in Minnesota and the Musi in Telangana, Muppidi realizes that his writing can only happen in the confines of “rooms secured with colonial and postcolonial pipelines.” From these small rooms “where books flow ceaselessly out of diverse terminals,” he can hear “a lot of agitation and energy out there.” This agitation is made up of the voices and rhythms of the “villagers and villages near and far.” He can feel their music and murmurs, their excitedly moving bodies. But the books on his walls, “English and Telugu alike,” muffle the sounds from these places. Muppidi writes:

Sometimes, if the winds and tubes and screens carry them right, the books are helpless against the music and the dancing and I feel a need to venture out of these small rooms … and wade into these new sources of epistemic energy. More often than not, however, I content myself with catching some notes and pulling together worldly pages on what those beats … those lyrics, do to me or mean to my body. Writing them down, recording them, in the confines of these rooms, is more compelling than joining the dances in the streets and towns and villages sprawling outside. … Could it be because, in this world of small rooms … politics should always be parlayed into newer and newer fabrications? Or, is it because my academic body, an assemblage of so many words, is incompetent at engaging politics otherwise?2

The idea of hungry translations is fired, in many ways, by the restlessness of those who believe in cracking the book-studded walls in the “world of small rooms” by bringing them into vibrant, even disturbing, epistemic conversations with the bodies “out there” that sing, perform, and protest. I engage the truths that often become muffled when words from one place are translated into more words of another language and robbed of their accents, melodies, and meanings; when the words are not accompanied by the embodied vocabularies and gestures that give them life after they are uttered. I am concerned about that which cannot be heard, seen, sensed, or felt through words alone, especially when those words are written down and caged in a regularized structure, in familiar fonts, in a predictable sequence of black and white pages. The translations I argue for emanate from long-term journeys with companions in multiple sites: journeys that produce yearnings for ways to refuse the seclusion of the small book-walled rooms and to build situated solidarities with those who protest and dance “out there,” without romanticizing “their” voices and movements. These journeys hunger to continue to learn ways of being and doing that can make our collective knowledges abide by the terms of the struggles we stand with, even as they escape the limits imposed by the disciplined terms of the academy.

Learning from such journeys involves recognizing and sharing our most tender and fragile moments, our memories and mistakes, in moments of translation. This mode of being approaches translation as an act of love or radical openness that also unsettles and disrupts. To use Emily Apter’s words, translation becomes a tool to reposition the subject “in the world and in history”—a way of denaturalizing citizenship by “rendering self-knowledge foreign to itself.”3 By embracing these challenges through an anti-definitional stance that uproots and reroots, I offer hungry translations as an agitation. This agitation narrates people, stories, events, and dreams through collectively owned journeys not in a hope to reach perfection, but in a hope to disorder the dominant languages and paradigms through which we often encounter knowledges and knowledge makers.

To begin performing these hungry translations, I would like to introduce some of the co-travelers from whom I have learned a few things about the undisciplined arts of translation, and about the embodied politics and pedagogies of hunger, hope, and knowledge making. Among these teachers are saathis of Sangtin Kisan Mazdoor Sangathan (SKMS), a movement of eight thousand kisans and mazdoors, most of them Dalit, working in 150 villages of Sitapur District.4 The Sangathan, SKMS, fights for dignity and justice for its saathis or members and companions, and refuses what Joyce King, building on Sylvia Wynter’s discussion of néantisé in the writing of Édouard Glissant, calls epistemological nihilation. Specifying that nihilation is not the same as annihilation, King defines it as “the inherent denial or total abjection of one’s identity and beingness.”5 For SKMS, a refusal to be nihilated means rejecting the discourse where Dalit kisans and mazdoors are reduced to the status of being the ‘poorest of the poor’ or as being on the ‘margins’ and therefore unable to produce and mobilize knowledge and politics to better their own situation. This refusal goes hand in hand with SKMS defining itself as a Sangathan of kisans and mazdoors who are Dalit—a term that literally means “crushed down” and constitutes an identity of dignity and self-assertion, “a democratic identity of the socially oppressed untouchable caste groups.”6 The Dalits in SKMS include about two hundred Muslims; in addition, approximately 150 members are from Other Backward Classes (OBCs) or Savarna castes.7 The movement emerged from the writing of a book called Sangtin Yatra, or a journey of sangtins, that eight rural women activists and I undertook in Hindi and Awadhi between 2002 and 2004.8 Since then the stories from the book, and stories of the book’s aftermath, have traveled as translated texts in multiple languages, including English, Turkish, Marathi, and Bahasa Indonesia. Along with this dance of the text across locales and languages, the people’s movement in Sitapur has become a crucial part of my life regardless of my physical location: I have worked with and learned from the saathis in my roles as a scribe, a coauthor, a theater worker, and a co-strategist from near and far. As I have wrestled with the intricacies and dilemmas of my task as a storyteller of SKMS in multiple languages and genres, my labor and passion as a member of the US academy have become necessarily centered on the interbraided praxis of ethical responsibility, situated solidarities, and authorship within and across borders and hierarchies in ongoing movement. This praxis grapples with how to continuously strive to do justice to the accents, melodies, and meanings of that which the singing, dancing, and rallying bodies offer to us, and which cannot be contained or conveyed by the languages and frameworks available to us. To develop this discussion, I share three moments from my journeys with SKMS.

Standing Together: Introducing Sunita and Tarun

Everyone who finds out about it in the village of Kunwarapur rushes to the SKMS dairy.9 It isn’t every day, after all, that the meetings of the Sangathan involve an actor from Mumbai. SKMS has invited Tarun Kumar, a theater artist who has been following sangtins’ yatra, all the way from Mumbai to Sitapur to help create a play, and the energy that is emerging in the village is intoxicating.

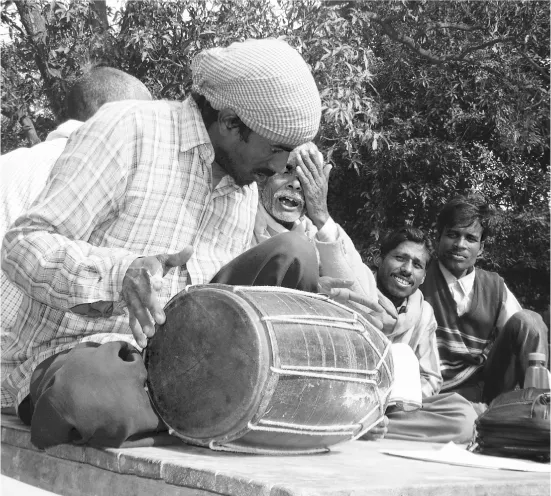

The cold damp fog has been trying to take over the morning again, but today the sun has decided to bless this January day. This is an auspicious beginning of our theater work because many more people will be able to join us now. A cluster of nine people gather on a tiny coir khatiya, threatening to break the poor cot into pieces, while another six sit on the periphery of a rectangular wooden takht where Tama sets himself up with his dholak, next to Pita, Kamlesh, and Richa S. As people pour into the meeting ground, Reena and Shamsuddin rush inside to get two daris and spread them by the cot and the takht. This extra seating vanishes in seconds as enthusiastic young women of Kunwarapur, bahus and bitiyas alike, grab a spot wherever they can find it.10 Outside this circle of seated people stand dozens of people, young and old. When children who try to peek in find their gaze blocked by adults, some men plant them on their shoulders while others bounce them up onto the seats of the bikes that the passersby have halted at the scene of the theater workshop on their way to the fields.

“But where is Sunita?” someone asks.

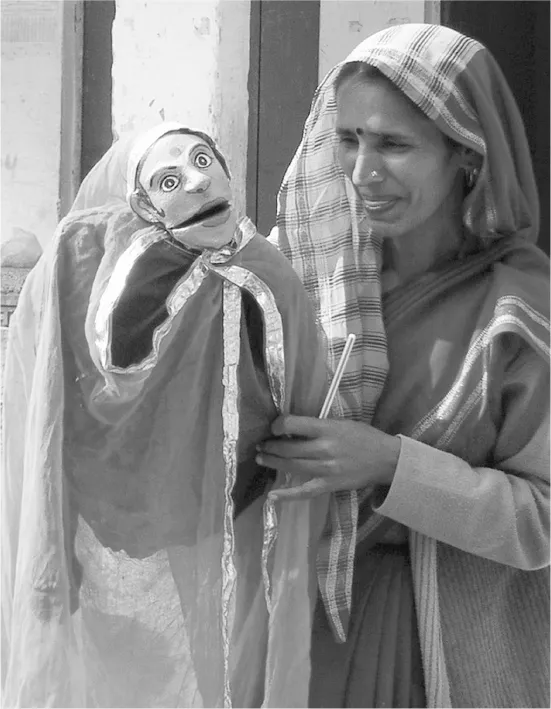

Sunita, an active saathi of SKMS, lives right next to the dairy. Those from Kunwarapur already know that she cannot join us because her young daughter is burning with high fever. Someone murmurs that the poliovirus might have attacked the daughter. There is a shared moment of pause, as if to collectively recognize the sorrow and dread that Sunita must be feeling, and then begin the vigorous beats of Tama’s dholak, with Pita’s voice reaching the sky, while Saraswati Amma claps and dances, and the perky glove puppet called Rani jumps around, causing commotion under the direction of one hand after another.

Reena with Rani, the puppet. (Photo by Richa Nagar)

Sunita can hear every sound of her saathis acting and singing while she tends her daughter; she finds it impossible to stay away from this scene of spirited activities. She asks a friend to take care of her daughter for a couple of hours and joins the group. Grabbing the dholak from Tama, she circles around the crowd asking for punishment for all the village development officers who steal the wages of the laborers and leave their children to die. Throughout the day, saathis have been poking fun at the dishonest development officials who corrupt the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA).11 NREGA aims to enhance livelihood security in rural areas by providing at least one hundred days of wage employment in a financial year to every household whose adult members volunteer to do “unskilled” manual work. Sunita’s arrival at the scene introduces a rage and rebellion into the performance. Yet, several of us cannot focus entirely on what she is saying or doing. Our hearts thud with fear about what awaits her at home at the end of the rehearsal.

Tama’s beats match Pita’s notes while Kamlesh and Sarvesh look on. (Photo by Richa Nagar)

As a brand-new visitor to SKMS, Tarun feels especially uncomfortable—perhaps even a bit guilty—about the circumstances in which Sunita has been moved to participate in the theatrical activities. At the end of the day as everyone begins to leave, Sunita comes to Tarun and takes his hand in hers to thank him and to say good-bye. Tarun is at a loss for words. He wants to do something to show his appreciation for the enormous contribution she has made to the group’s work despite her dire circumstances. Not being able to come up with anything else, he sticks two currency notes in Sunita’s palm and gently closes it into a fist. Sunita does not flinch or speak. Without looking down at her fist or at what has been inserted in it, she opens Tarun’s palm, places the money back into his hand, and then gently closes his fingers just like he had done with hers. For a wordless second, she looks straight into his eye, then she says softly and firmly, “You keep this, Bhaiyya. Give us your dua by standing with us.” Calling him a brother, Sunita asks for Tarun’s blessings in a way that seeks his solidarity with SKMS, but without defining for him what that solidarity might look like.

Sunita takes the dholak. (Photo by Richa Nagar)

”My Voice Rising in Your Chest”: Introducing Tama

Suddenly, the sun comes out and brings a brief respite from another wintry day in Pisawan.12 It is that time of the year when the cold, damp, and heavy fog rules for weeks at a stretch. Opening his left hand, as if to catch the sunshine between his palm and fingers, Tama pulls the dholak closer to him. His poor vision prevents him from clearly seeing the many pairs of eyes that are watching him, but his fingers gently explore every line, curve, and texture of that dholak. Watching Tama adjust his dholak with that familiar longing, the saathis at the theater workshop with Tarun immediately stop their discussion on what kind of play they want to create on the current status of corruption the villagers are subjected to under MGNREGA. They know that Tama wants to sing, and now.

In order to give special effects to the beats on the dholak, Tama begins to tie a thin stick to the index finger of his right hand with a nylon string. As the string continues to tighten around his finger, Tarun remarks: “Tama, why are you making it so tight? Your blood will stop moving.”

Tama laughs as he wraps the string around his finger one more time—“So what?” he says, locking his gaze into Tarun’s, “The string will only stop the blood from moving. It won’t stop my voice or my dholak’s dhamak from rising in your chest!”

After several hours of chatting, parodying, playing, and singing that day, Tama starts getting ready to go home before everyone else. A couple of saathis ask Tama to stay. “Why are you going home? Hang out with us in Sitapur tonight. It will be fun.”

“My mother and I have guests visiting.”

“We are also your guests,” Tarun smiles at him. “Why not stay with us tonight?”

Tama is visibly moved by Tarun’s affectionate insistence that acknowledges a special kinship between them. With a wide grin that lights up his face, Tama claps in his inimitable style, and building on Tarun’s words, he immediately takes the exchange to a deeper level—“No, not tonight, Bhaiyya. Tonight, my mother will cook paraanthas. I promised to buy some oil for the paraanthas.” Tama swiftly reaches into the left pocket of his khaki pants and pulls out a small glass bottle the size of Tarun’s finger, and the two exchange a long glance. Among the things said and learned in the glance—not only by them, but also by anyone who witnesses that moment—are the complexities of the terrain on which all of us have decided to walk together as saathis of SKMS.

No Living without Nautanki: Introducing Prakash

We are meeting as a group by Skype after a long time. Kamal, Mukesh, Rambeti, Richa S., and Prakash have joined in from Richa S.’s home after sharing a meal in Sitapur at night while I am sitting alone with my morning cup of chai in my kitchen in Saint Paul. The sunlight from the window is gently tickling my back on this cold March day. Sitting on a slim Ikea chair next to the stove, I adjust the screen of my laptop and see my saathis spending another night talking and sharing and growing together under the same roof. I miss the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Photographs

- Series Editor’s Foreword

- Note on Transliterations, Translations, and Poems

- Aalaap

- Part One Staging Stories

- Part Two Movement as Theater: Storylines, Scenes, Lessons, and Reflections

- Part Three Living in Character: “Kafan” as Hansa

- Part Four Stories, Bodies, Movements: A Syllabus in Fifteen Acts

- Closing Notes: Retelling Dis/Appearing Tales

- Backstage Pages

- Glossary of Selected Words and Acronyms

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index

- Back Cover