- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A renaissance in Illinois history scholarship has sparked renewed interest in the Prairie State's storied past. Students, meanwhile, continue to pursue coursework in Illinois history to fulfill degree requirements and for their own edification.

This Common Threads collection offers important articles from the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. Organized as an approachable survey of state history, the book offers chapters that cover the colonial era, early statehood, the Civil War years, the Gilded Age and Progressive eras, World War II, and postwar Illinois. The essays reflect the wide range of experiences lived by Illinoisans engaging in causes like temperance and women's struggle for a shorter workday; facing challenges that range from the rise of street gangs to Decatur's urban decline; and navigating historic issues like the 1822-24 constitutional crisis and the Alton School Case.

Contributors: Roger Biles, Lilia Fernandez, Paul Finkelman, Raymond E. Hauser, Reginald Horsman, Suellen Hoy, Judson Jeffries, Lionel Kimble Jr., Thomas E. Pegram, Shirley Portwood, Robert D. Sampson, Ronald E. Shaw, and Robert M. Sutton.

This Common Threads collection offers important articles from the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. Organized as an approachable survey of state history, the book offers chapters that cover the colonial era, early statehood, the Civil War years, the Gilded Age and Progressive eras, World War II, and postwar Illinois. The essays reflect the wide range of experiences lived by Illinoisans engaging in causes like temperance and women's struggle for a shorter workday; facing challenges that range from the rise of street gangs to Decatur's urban decline; and navigating historic issues like the 1822-24 constitutional crisis and the Alton School Case.

Contributors: Roger Biles, Lilia Fernandez, Paul Finkelman, Raymond E. Hauser, Reginald Horsman, Suellen Hoy, Judson Jeffries, Lionel Kimble Jr., Thomas E. Pegram, Shirley Portwood, Robert D. Sampson, Ronald E. Shaw, and Robert M. Sutton.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Illinois Historical Journal Vol. 86, No. 4 (Winter 1993): 210–224

1.The Fox Raid of 1752

Defensive Warfare and the Decline of the Illinois Indian Tribe

RAYMOND E. HAUSER

ON JUNE 1, 1752, THE FOX INDIANS led an intertribal force of between four hundred and five hundred raiders on a surprise attack against the Cahokia and Michigamea Illinois Indian village located on the east bank of the Mississippi River, a short distance north of Fort de Chartres.1 Specialists have long recognized that American Indian raiding warfare expeditions grew larger after contact with Europeans, but the size and composition of that particular raiding party even caught the attention of French cartographer Jacques Nicolas Bellin in 1755.2

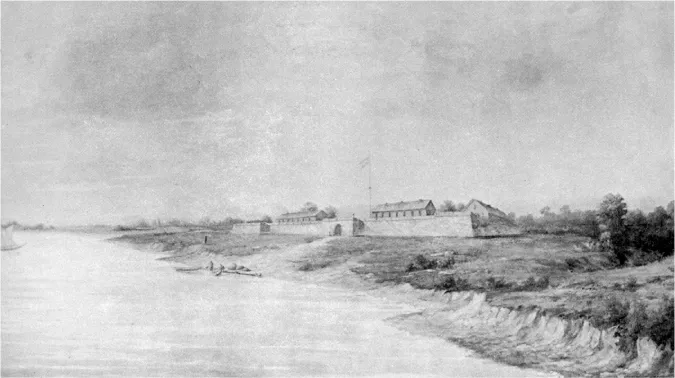

Fort de Chartres, from a mural in the Illinois State Capitol.

While scholars have often referred to the raid, their purposes have not required a thorough examination of it or its implications.3 In one of the more extensive and error-laden reviews of the attack, Lawrence Henry Gipson, an influential twentieth-century historian, employed it as an example of the difficulty encountered by the French while attempting to control their Indian allies, and he was probably incorrect here, also.4 The Fox raid of 1752 was a significant event for the Illinois Indian tribe because it emphasizes the inadequate implementation of defensive raiding warfare precautions, it sheds light on Indian-white relations, and it focuses attention on the role warfare played in explaining the population decline of the Illinois.

The subtribes of the Illinois and their neighbors must have maintained a fully developed raiding warfare tradition for at least a generation prior to the arrival of the Europeans. The influence of Europeans caused Native Americans to adapt their concept of war to include communal war during the protohistoric period5 and to adapt raiding warfare by including firearms and much larger raiding expeditions early in the historic period. While the Illinois launched and received larger expeditions prior to 1752, the raid executed by the Fox and their allies from various northern tribes offers a clear example of how inadequate defensive raiding warfare had become, compared to the devastating dimensions of postcontact offensive operations.

The Cahokia and Michigamea constituted subtribes of the Illinois, which also included the Kaskaskia, Moingwena, Peoria, and Tamaroa.6 The Illinois had been subdividing into separate tribes when the arrival of Louis de Jolliet and Jacques Marquette in 1673 opened the historic period in the Illinois country, but that process was halted and then reversed by conditions that attended contact. The tribe occupied most of the present state of Illinois from at least the late 1630s until “the middle of the eighteenth century.”7 The Illinois suffered a disastrous population decline during the historic period,8 and pressures from other tribes encouraged the Peoria eventually to settle on the Illinois River at Lake Peoria. The Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Michigamea moved southwest to the American Bottom along the east bank of the Mississippi River below the mouth of the Missouri. The French built forts close to all four of those Illinois villages.

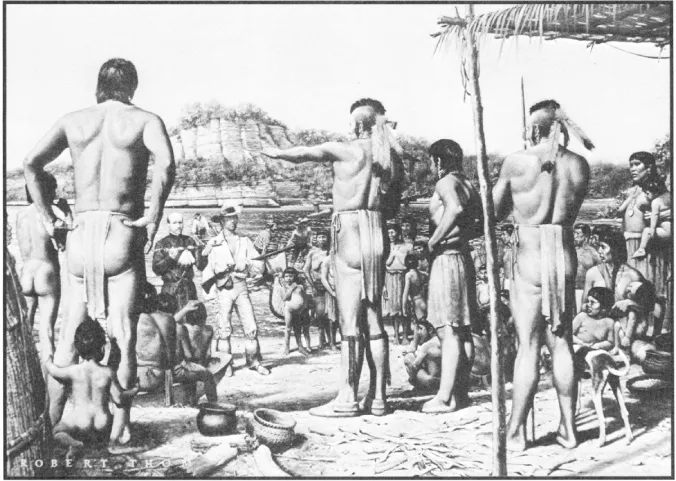

This painting by Robert Thorn, which hangs in the Illinois State Historical Library, depicts the arrival of Father Louis de Jolliet and Jacques Marquette, the first Europeans to make contact with the Indians of the Illinois country.

As Prairie Siouan culture peoples, the Fox and the Illinois shared the same traditional raiding warfare practices. Among the Illinois, for example, military success provided warriors with status recognized in victory ceremonies, martial tattoos, and burial rights. The Illinois regularly fought the Fox, Sioux, and five or six other tribes in a continuous state of war in which peace was only a temporary truce. The primary motive was revenge, but prestige, adventure, and economic advantage were additional factors. War chiefs were self-selected, and warriors volunteered to participate in their war parties in numbers that varied between six or seven and twenty. Raiders employed tactics that emphasized stealth, surprise, and ambush, and their weapons included bows, arrows, knives, clubs, and shields. War parties traveled as far as 1,250 or fifteen hundred miles, moved cautiously at night in enemy territory, and attacked at dawn. They killed enemy women and children on the spot, but retreated quickly with warriors, who were usually tortured to death at the Illinois village.9

Contact with Europeans brought fundamental changes in warfare, which included communal or raid-in-force expeditions, targeting women and children as prisoners; younger warriors; metal arrow heads, knives, and clubs; and, of course, firearms. Warfare thus became much more deadly.10

The stealth, ambush, and surprise elements of raiding warfare conditioned Illinois defensive efforts. They built their semipermanent summer villages in river valley locations, with the cabins arranged along the banks of the river or on the edge of a prairie in order to avoid surprise attacks and facilitate launching retaliatory pursuit.11 The Illinois despised men who were reluctant to pursue raiders, considering them cowards.12 Defenders utilized the same weapons employed by raiders, and civil chiefs—relying on their own military experience—probably organized defensive arrangements. The presence of enemies was often discovered by women working in fields, by hunters, and by scouts returning from enemy territory. Even with numerous dogs, village defenses were usually quite lax. Enemies alerted to their peril were considered so dangerous, however, that the raiders “would need [a] ten to one [advantage]; and moreover, on those occasions each one [of the raiders] avoids being the first to advance.”13

Traditional Illinois defensive maneuvers also included moving villages to island locations, combining villages, removing them from the proximity of dangerous foes, and organizing defensive alliances against particularly troublesome enemies. Despite the increasing danger from raiders following contact, the Illinois did not often construct protective stockades around their villages prior to 1752.14 The French instructed the Illinois “in the art of fortification” as early as 1680,15 but the Illinois economic cycle, which required frequent moves, probably discouraged them from expending the effort required to erect palisades. They continued to rely on the presence of French military power—including French forts—for protection. Dependence on French forts required timely warning in the event that several small war parties or a large raid-in-force was directed against them.16 That warning was unavailable on June 1, 1752.

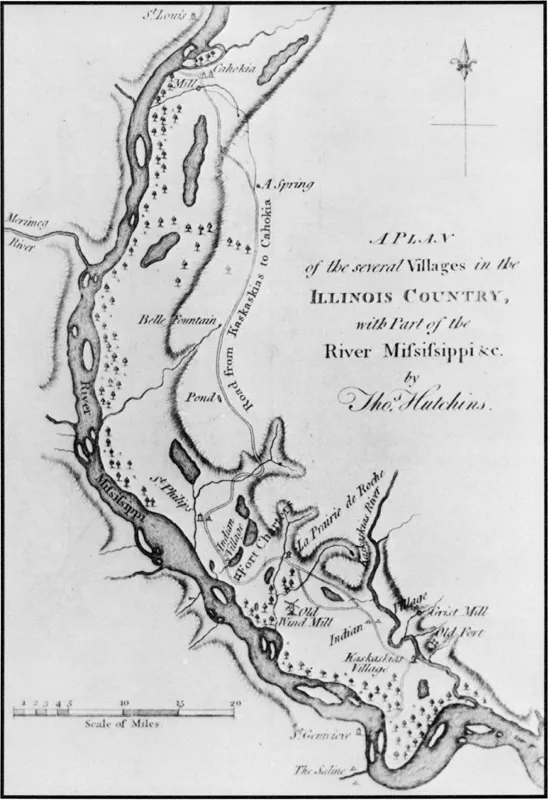

This 1771 map of the Illinois country by Captain Thomas Hutchins shows the proximity of the Indian villages to the French forts and settlements.

The declared origins of the 1752 raid-in-force may be found in the culture-driven competition of raiding warfare. The Fox rationalized that the immediate reason for the attack was the Cahokia aggression of 1751, which violated a peace with the northern tribes arranged by the French. While the Cahokia were “out on a hunting trip,” they captured seven Fox and tortured them. Jean-Bernard Bossu, a French officer and the only eyewitness to write an account of the raid, does not explain where the Cahokia executed the captives, but he does relate the experiences of the Fox prisoner who escaped and endured tremendous hardships during the journey to rejoin his tribe.17

The Fox were, of course, distressed at the news that the survivor brought, and they determined to carry out a remarkable revenge. Even if the provocation had not been so compelling, the Fox would have retaliated because of raiding warfare traditions, the economic and military alliance between the Illinois and the French, and the desirable geographic position occupied by the Illinois. According to Bossu, the Fox chief “assembled his men [after the return of the survivor], for nothing is done without a council, and they decided to send bundles of twigs to the chiefs of allied tribes … who [eventually] marched as auxiliary troops under the standard of the Foxes.”18 Although it is not possible to estimate the number of warriors contributed to the venture by the various tribes, the number of Illinois prisoners awarded the Sauk after the attack suggests that they made up a considerable part of the expedition.

The Cahokia expected a Fox retaliatory raid. Deciding that their village position and numbers placed them in some jeopardy, they abandoned the village located since 1735 about nine miles north of the French village also named Cahokia.19 The Seminary of Foreign Missions had maintained a missionary program in the Cahokia-Illinois village.20 The Cahokia took a traditional defensive step when they moved about forty-five miles south and relocated with their Michigamea relatives in the village positioned just one and a quarter miles north of Fort de Chartres, a distance probably required in order to promote harmony between the two communities.21 Nevertheless, in 1721, Father Pierre de Charlevoix noted that “the French are now beginning to settle the country between this fort [de Chartres] and the first mission.”22 The Michigamea, who had occupied that summer village for more than thirty years, extended refuge to the Cahokia because they shared a “fear of being attacked by the Foxes in reprisal,” and they also hoped to share the security offered by the larger population of a combined village.23

The Cahokia and Michigamea village had a population that might be estimated at fewer than four hundred “of all ages.”24 A village of four hundred would have had an adult male population of about ninety-six who were “capable of bearing arms,” and would have contained approximately twenty-four or twenty-five large cabins.25 The Michigamea had entertained Jesuit missionaries in their village, but because the Illinois had not accepted Catholicism in sufficient numbers and because of the unavailability of a missionary, the village was without one by 1750.26

The village probably had its dwellings arranged in “the lineal pattern of the Illinois” that was “spread out, scattered along the bank” of the Mississippi.27 The Michigamea did not protect the village with a palisade. It was placed so that it “was surrounded by woods and a ravine.”28 Agapit Chicagou served the Mic...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. The Fox Raid of 1752: Defensive Warfare and the Decline of the Illinois Tribe

- 2. Great Britain and the Illinois Country in the Era of the American Revolution

- 3. Edward Coles and the Constitutional Crisis in Illinois, 1822–1824

- 4. Slavery, the “More Perfect Union,” and the Prairie State

- 5. “Pretty Damned Warm Times”: The 1864 Charleston Riot and “the Inalienable Right of Revolution”

- 6. “Honest Men and Law Abiding Citizens”: The 1894 Railroad Strike in Decatur

- 7. The Alton School Case and African American Community Consciousness, 1897–1908

- 8. The Dry Machine: The Formation of the Anti-Saloon League of Illinois

- 9. Chicago Working Women’s Struggle for a Shorter Day, 1908–1911

- 10. “I Too Serve America”: African American Women War Workers in Chicago, 1940–1945

- 11. From the Near West Side to 18th Street: Mexican Community Formation and Activism in Mid-Twentieth Century Chicago

- 12. A Final Push for National Legislation: The Chicago Freedom Movement

- 13. From Gang-Bangers to Urban Revolutionaries: The Young Lords of Chicago

- 14. The Decline of Decatur

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Illinois History by Mark Hubbard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.