![]()

1 Iglulik Inuit

Drum-Dance Songs

PAULA CONLON

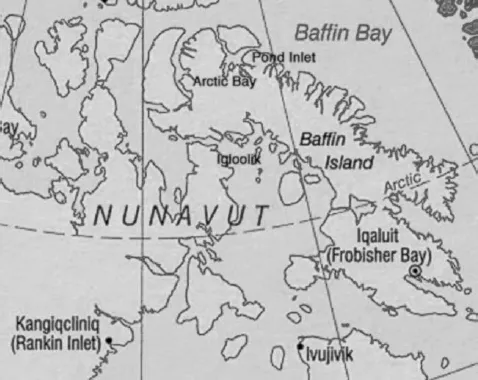

This article discusses the traditional musical style that dominates the Inuit from the Arctic East to West: the drum-dance song, or pisiq (plural pisiit).1 The syllabic a-ya-ya, which appears in the text of drum-dance songs from Alaska to Greenland, is used today to designate the whole of the song as well. The 315 drum-dance songs that provide the basis for this study are from the Iglulik Inuit area of northern Baffin Island. The songs were collected from the following hamlets: Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet) (collected by Jean-Jacques Nattiez in 1976 and 1977), Igloolik (Nattiez in 1977), and Ikpiarjuk (Arctic Bay) (Lorne Smith in 1964 and Paula Conlon in 1985) (see Figure 1.1).2

The Iglulik Inuit of the present day are descended from the people who brought the Thule culture into the Baffin Island area around AD 1200. In 1822 Captains William Edward Parry and George Francis Lyon of the Royal Navy spent the winter at Igloolik during their search for the Northwest Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans. When ethnologists Knud Rasmussen, Peter Freuchen, and Therkel Matthiassen arrived in Igloolik in 1921, they found the way of life still very much as it had been one hundred years before. Hunting was the chief activity, with char fishing as a supplementary activity performed by women (NWT 1990–91: 168).

The period 1920–60 has been referred to as the era of the “big three”: the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the Hudson’s Bay Company, and the missions (Mary-Rousselière 1984: 443). In the 1960s, the Canadian government began systematically regrouping the Inuit around these installations. Modern aluminum houses were built in the hamlets of Admiralty Inlet, Sanirajak (Hall Beach), Igloolik, Ikpiarjuk, and Mittimatalik, and the government set up federal schools in Igloolik (1959), Mittimatalik (1960), and Ikpiarjuk (1962), with compulsory education for all children ages six to sixteen. The Inuit move freely among these communities, but the nomadic way of life, based on hunting and fishing, disappeared in fewer than ten years.

Figure 1.1. Map of Baffin Island. Courtesy of Tara Browner. Map template taken from public domain collection of the Perry-Castaneda Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin.

As the fieldwork for this study was carried out after the government’s regrouping of the Inuit in the 1960s, these songs were all collected “artificially.” The singers were asked to sing for the sole purpose of being recorded, with the result that the musical style of the recordings was sometimes affected by contact with white musical civilization and modern conditions of performance. In this sense, the collection represents the musical state of the Iglulik Inuit between 1964 and 1985 (Conlon 1992).3

Song Composition

Traditionally, a man composed a drum-dance song in solitude, usually while hunting. Once he had decided on the text and the melody, he repeated the song over and over so as not to forget it. When the hunter returned home, he taught the song to his wife, who in turn taught it to the other women in the village, to be ready for a public performance at the feasts (qarginiq). The women’s role is paramount because “the woman is supposed to be the man’s memory” (Rasmussen 1929: 240). When the composer was a visitor, he taught his song to the women of the host camp before the drum dance (Uyarak 1977).

There is no report, either from ethnographic sources or from consultants, of women dancing with the drum in the Iglulik area.4 Rasmussen notes that every man and woman, and some of the children, may have their own songs (with appropriate melodies) that can be sung in the qaggi (dance house) (1929: 227), but there is no information about how the women’s songs are presented. Of the 147 drum-dance songs (of known authorship) from Igloolik, Ikpiarjuk, and Mittimatalik, only 4 are attributed to female composers.

Although the character of Iglulik Inuit drum-dance songs is personal, this is not in the sense of property such as that exhibited by some North American Indian cultures. For instance, it is not necessary to ask permission before singing someone else’s song (Nattiez 1988: 45). An indication of the lack of possessiveness of songs is the availability of portions of common text in personal songs by different composers. During my fieldwork in Ikpiarjuk in 1985, many of the singers spoke about the communal aspect of the singing of another’s songs, saying that public acknowledgment of the original creator of the song was sufficient. Interviews from Nattiez’s fieldwork in 1976 and 1977 indicate a similar attitude toward song ownership at Mittimatalik and Igloolik.

Song Texts

The text in drum-dance songs is in large part linked to basic experiences in the Inuit way of life. Topics of songs include hunting, people, death, qallunaaq (white man), singing, and religion. As hunting is essential for survival and is the primary activity during which songs are created, it is not surprising to find that the theme of 68.5 percent of the song texts revolves around some aspect of hunting, as in this song: “The polar bear over there, I see it over there, ayaya … My harpoon, I suddenly want it now, ayaya. … My dogs there, I suddenly want them now, ayaya …” (Panipakoochoo 1977: 5d-84.PI77-10).5

The qallunaaq category (4 percent of songs) includes eight versions of a song dealing with “this little hook,” a feature of the syllabic alphabet used by missionaries in biblical translations (NWT 1990–91: 196). Whalers brought examples of these syllabic-print Bibles to Mittimatalik before the arrival of the missionaries in 1922 (Qango 1977), but the Inuit had no instruction in the use of the alphabet. The text is: “This little hook shape, I wish I could find out what it is, ayaya, I-E-OO-A-pie-pee-poo-pa, ayaya” (L. Kalluk 1985: 4g-3.AB85-30).

Songs listed under “singing” (4 percent of songs) deal with the process of composition and the frustration of attempting to create something new: “It turns out nothing was left for me, no future songs at all, ayaya. … Somebody said they were all gone. Our ancestors used up all the songs, ayaya …” (Ikaliiyuk 1977: 5e-15.IGL77-88).

Drum Construction

The Inuit drum (qilaut) averages approximately seven inches in diameter but is known to vary in diameter from five to thirty-four inches.6 Drums from the eastern Arctic are typically larger than those found farther west. Figure 1.2 is a drum made by Aglak Atitat of Ikpiarjuk in 1985. Its diameter is twenty-three and a quarter inches.

To construct a drum, a wooden frame is bent by means of steaming and soaking.7 The frame is then tapered and nailed together in a circle, and the skin is bound tightly to the frame with sinew or string. The same cord that binds the drumhead also ties the drum handle. Like the drum handle, the mallet is roughly shaped to fit the hand. The mallet is then covered with sealskin.

Drum Dances

Traditional drum dances were part of song festivals that usually took place in a large igloo called a qaggi, which could hold up to one hundred people. In order to announce a drum dance, someone would go out and shout for everybody to come over: “It was just like a community hall” (Uyarak 1977). In the qaggi, drum-dance competitions took place that generally involved the whole community. These festivals occurred when there was abundant food and generally started with a communal feast of caribou and seal. Festivals took place principally in autumn or winter, and sometimes took place between teams from different camps. Isapee Qango (from Igloolik) said that the length of the feast was usually around three days but could last up to five days (1977). Rasmussen notes that when there were visitors, the entertainment might go on all night, throughout the dark hours, which could be up to all twenty-four (1929: 228, 230).

Figure 1.2. Iglulik Inuit drum (maker: Aglak Atitat; collector: Paula Conlon; acquisition date: 1985).

No matter what form the competition took, there was clearly a winner. Along with the prestige gained, tangible prizes (such as harpoons) were sometimes awarded. The success of the song festival depended on the daily practicing of the songs by each family (Rasmussen 1929: 228). A more contemporary indication of this practice is that by François Quassa of Igloolik: “His mother-in-law used to sing a lot. … They used to live in one igloo, the whole family, in-laws, and everything. And she used to sing every night, before they went to sleep” (1977).

Structure of the Drum Dance

At the beginning of the festival, the drum (qilaut) was placed on the ground in the center of the qaggi. Any composer could start. When he took the drum, his wife began to sing his song. His wife was the leader (ingirtuq) of the choir (ingiortut) of women who had learned the song. The composer did not sing, although he cried out from time to time (Urrunaluk 1977).8 According to Rasmussen, “The mumirtuq (the dancer) will … often content himself with flinging out a few lines of the text, while his wife leads the chorus” (1929: 240). The term mumerneq, which means “changing about,” signifies the combination of the melody, the words, and the dance (Rasmussen 1929: 228).

While drum dancing, the man dances slightly bent over, holding the drum with his left hand (a left-handed man holds the drum in the right hand). With his wrist he pivots the drum from right to left. He uses the mallet (katutarq), covered with sealskin, to hit the wooden frame, alternately on the base (akkirtarpuq) and the top (anaulirpuq) of the drum. The feet are often synchronized with the beat of the drum to avoid fatigue (Urrunaluk 1977). Some drummers are so skillful in the handling of the drum that they can make it pivot in the air from side to side without holding the handle (Iyetuk 1977; Kupak 1977).

When the first dancer at a drum dance was finished, another took his place. The elder men present evaluated the merits of each song and dance. Although the competitive character of the traditional drum dance could take various forms, it was mainly a test of endurance to determine the capacity of the dancer to “hold the beat.” The longer the song, the heavier the drum seemed to become, and the large size of the drums from the eastern Arctic contributed to the difficulty. The number of songs known was also taken into consideration. In the hamlet of Igloolik, the song was said to wrap itself inside the wooden frame of the drum (Iyetuk 1977; Urrunaluk 1977), and the drum itself was considered responsible for the hardship of performing (Ikaliiyuk 1977).

Song Cousins and Song Duels

The competition could involve all the men participating at a festival, but often it was specifically between illuqiik (singular illuq), that is, “song cousins.” This strong friendship was formed by mutual consent, signified by an exchange of wives, pleasantries, and food. At the feasts, song cousins took turns confronting each other with insult songs (iviut). But as Rasmussen points out, “Song cousins may very well expose each other in their respective songs, and thus deliver home truths, but it must always be done in a humorous form, and in words so chosen as to excite no feeling among the audience but that of merriment” (1929: 23).

Drum-dance competitions were also used to resolve serious disputes and involved vicious songs of derision. Rasmussen describes the song duel: “Here, no mercy must be shown; it is indeed considered manly to expose another’s weakness with the utmost sharpness and severity; but behind all such castigation there must be a touch of humour, for mere abuse in itself is barren, and cannot bring about any reconciliation” (1929: 231).

Social humiliation was the principal means of defeating one’s opponent, although these t...