![]()

Bathed in the Fading Light

“I don’t feel part of life. I always felt as though I were a spectator.”

—Terence Davies

The cinema of the British director Terence Davies is one of contradictions—between beauty and ugliness, the real and the artificial, progression and tradition, motion and stasis. These opposites reflect a certain struggle, for the filmmaker and his characters, to make sense of a confusing and sometimes violent world. For Davies, this struggle constitutes a reckoning with his past, a highly personal account of a fractured childhood; for the viewer it has resulted in one of the richest, most idiosyncratic, and arrestingly experimental bodies of work put out by a narrative filmmaker. This struggle is particularly acute because Davies, a gay man who has long accepted his homosexuality yet has also often vocalized the shame he feels about it, is constantly negotiating issues of identity in his work—both his own and those of his characters. Davies’s world is a personalized vision of the twentieth century refracted through a decidedly queer prism.

A recurring image in Davies’s films shows someone staring out of a window. A character faces the camera, looking onto a world that has confounded, betrayed, or oppressed. This specific visual bestows great power on both his first film, 1976’s forty-six-minute Children, and 2011’s The Deep Blue Sea, his most recent feature at the time of this writing. The first is a spare, black-and-white work of tortured, fictionalized autobiography, recounting the filmmaker’s traumatic coming-of-age in grim, mostly static compositions; the latter is an adaptation of a 1953 play by Terence Rattigan about a married woman’s self-destructive affair, shot through with a seductive, rich classicism that could almost be called luxuriant. Worlds apart in many ways, the films are united by the manner in which their maker’s presence is felt within them, never more strongly than in those images of the protagonist gazing out at us, past us, at a universe he or she doesn’t understand, and which hasn’t taken the time to understand the person contemplating it.

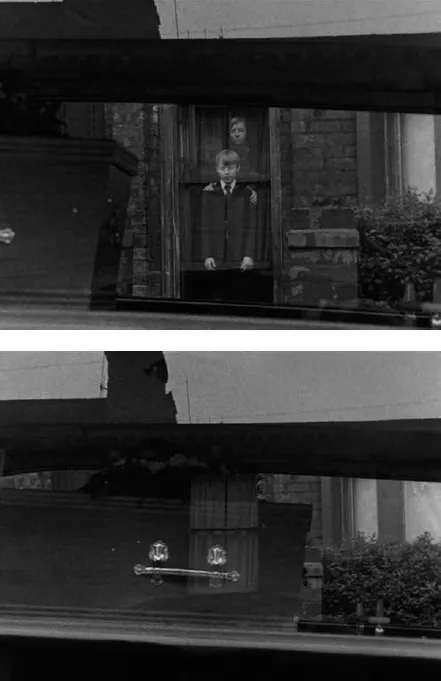

At the climax of Children, Davies’s pubescent surrogate, Tucker (Philip Mawdsley), has been affected by twinned traumas: he is slowly becoming aware of his incipient homosexuality, and he has lost his father to pancreatic cancer. Though the director has shown us the older man writhing in pitiful agony, we have not been invited to feel sympathy for him: he has been depicted as a tyrant, beating Tucker’s mother in a splenetic rage. Thus his death evokes in Tucker not sadness but mixed feelings of horror and joy, perhaps even more difficult emotions with which to reckon than had he merely been driven to mourn. With one shot—remarkable for its technical virtuosity and its ability to encapsulate warring feelings—Davies makes this moment unbearably vivid as well as metaphorically resonant. It is the morning of the funeral, and he has trained his camera on the front door of Tucker’s Liverpool row house, the camera patient and still as the coffin is carried out. Tucker walks into the frame, flanked by his mother and a couple of unnamed female mourners. Their ghostly faces peer out from behind the window’s cross-shaped grilles, which dominate the image. In a technical move that would prove uncommon in Davies’s cinema, the camera slowly zooms out on this haunting tableau (Davies would later rely on tracking and crane shots rather than zooms for such flourishes); in this shot, Tucker’s mouth breaks into a broad smile, one that only he could be aware of since the other mourners are positioned behind him. It’s an eerie image, wholly incongruous with the melancholy scene, yet Davies’s masterstroke is to come. The camera continues to zoom out, until the hearse enters the foreground; the coffin is mounted into the car from left to right, and as it slides into the back of the vehicle, its motion literally erases Tucker and his mother from the shot as though marks wiped from a chalkboard. The shot is made possible via a doublereflection of the front door and a second window across the street; the image conveys an extraordinary sense of both negation (the family unit’s erasure) and coming-into-being (Tucker’s smile connoting the possibility of a newfound happiness). A line from the single most influential work of art in Davies’s life, T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, comes to mind: “In the end is my beginning.”

The erasure of a family in Children.

The same sentiment could apply to the closing moments of The Deep Blue Sea. Though employing multiple flashbacks that give it the sense of a grand, time-hopping personal epic, the narrative proper takes place over the course of one day, following the night during which Hester (Rachel Weisz) attempts suicide via asphyxiation by gas heater. Over the film’s unfolding twenty-four hours, Hester—who in the years immediately following the war has left her loving and reliable but dull husband, a prominent and wealthy judge, for a romance with a young and handsome but penniless and emotionally unstable former RAF pilot—has tried to reconcile, or at least comprehend, the opposed halves of her embattled life. Whether she has come to any greater understanding of herself by the end of the film is left ambiguous, but we do know this: she has, for this one morning at least, chosen life. She throws open the heavy curtains, flooding her dingy boarding-house apartment with sunlight. Davies cuts to an exterior shot of her standing in the window, and before the camera cranes down and away from her (in a reverse mirror image of the film’s opening shot), we note the trace of a smile as Hester looks out. It is not as broad as Tucker’s, but her expression is similar: conveying the need to move forward yet clearly haunted by the past.

Davies is a cinematic auteur in the classical sense, authoring films from an unmistakably personal aesthetic and thematic standpoint. And if any true auteur’s protagonists are in some essential way their surrogates, then Tucker and Hester, wildly different beings at different points in their lives, are vivid incarnations of Davies himself. They exist at two disparate poles of his filmography, casting ambiguous smiles in the face of death. Joyous and melancholic, inside and outside, gazing at the world yet examining the self, moving forward but standing still, anticipating the future yet held by the past, they elucidate juxtapositions that reflect fundamental paradoxes—and as we’ll see, the queering agents—around which the rest of this book will revolve. These are films that would seem to function within the most identifiable of British cinematic traditions—broadly, that of realism—yet are just as often defined by fantasy, surreality, and subjective truth; that excavate a painful personal past by locating warmth, wonder, and pockets of happiness within; that are informed by classical Hollywood and British narrative traditions but use them as starting points for more daring experimentations of the cinematic form; that dramatize the progression of time by evoking times inherent falseness, implying that the present is simply an ever-persistent echo of the past and effectively illustrating Gilles Deleuze’s notion that in the modern cinema images no longer are linked by rational cause and effect but rather more obscure, sensorial continuities.

Considering the influence they had on his cinema, Eliot’s Four Quartets—the poet’s final major work, widely regarded as a significant achievement in twentieth-century writing—provide a useful starting point for discussing Davies’s particular kind of modernist memory film. Unifying four separate poems, three of which were composed in London during the darkest days of World War II, when the city was being bombarded by German air raids, Four Quartets (first published together as a book in 1943, two years before Davies was born) form a guttural, philosophical, and profoundly spiritual meditation on the nature of time and memory in what the author, who later in life had become an Orthodox Christian, perceived as an increasingly godless world. Each poem is named after a concrete place in Eliot’s past that he has imbued with rich metaphorical meaning: the first, “Burnt Norton,” invites the reader to contemplate the Edenic rose garden of a country estate and the enchanting and ominous memories it summons; “East Coker” is concerned in part with the artistic endeavor, specifically with how it helps us transcend the hopelessness of reality and escape the web of time; “The Dry Salvages,” awash in water imagery, partly recalls Eliot’s boyhood in Cape Ann, Massachusetts, to limn the edges of a baptismal eternity. Finally, with “Little Gidding,” Eliot tries to find peace in the attempt to reconcile the contradictory impulses inherent in the flow of life. As the Eliot scholar Russell Kirk writes, “Four Quartets point out the way to the Rose Garden that endures beyond time, where seeming opposites are reconciled” (241). Opposites also provide the philosophical foundation for Davies’s cinema, yet unlike Eliot, Davies outright rejects religious dogma, and therefore he is not able to reconcile the warring aspects of his life via a transcendent, sustaining spirituality. Nevertheless, the ultimate optimism in Eliot’s Four Quartets—which vibrate with hope, the possibility for human salvation and immortality through religion, without ever preaching a specific theology—appeals to Davies, as do the poems’ critique of the modern consciousness and their evocative, highly musical rhythm and structure. The past, present, and future all exist on one plane throughout the Four Quartets, as is the case with many of Davies’s films, which revolve and undulate rather than move in a straight line.

Davies’s films evoke Eliot’s words, “Time the destroyer is time the preserver.” It is essential to recognize and embrace the central paradoxes of Davies’s body of work to fully grasp and interpret it—and to realize how he has radicalized an essentially mainstream narrative cinema. Visually and sonically unorthodox, Davies’s films are highly aestheticized, and the curious nature of their approaches makes them difficult to situate. (If there has been occasional criticism of their distancing visual strategies, it has centered on the oddness of their hovering between realism and stylization—for instance, John Caughie was harsh on The Long Day Closes for what he viewed as “an aestheticization of drabness,” which he found at times to be “emotionally exploitative” [13].) Yet his defiance of easy genre categorization, his refusal to slot his films into established British or American cinematic traditions, and the manner in which he has put his distinct stamp on other writers’ material all eloquently speak to the way Davies has subtly created a queered filmography. He comes by his gentle radicalism naturally and genuinely; rather than setting out to complicate the unwritten rules of modern moviemaking, he seems to construct films as a way of locating a hidden lyricism—to create a poetics of trauma that narrows viewers’ common perceptions of the gulf between pain and pleasure, joy and grief, memory and fantasy. In so doing, he forces an unsettling destabilizing effect on his own cinema; the clearest way to explain his films’ essential queerness is to say that he seems to place them in recognizable generic forms, only to delegitimize those very forms. The word “queer”—a once-demeaning term used against gays and lesbians to negatively identify difference that was recouped in the early 1990s as a politically charged emblem of positive self-identification by those who were marginalized by it—describes a defiance to heteronormatively established categories of sexual identity, dissolving boundaries between male and female, gay and straight. We might say that Davies’s cinema, by virtue of its resistance to set aesthetic and political cinematic rules, similarly refuses either/or binaries. It is perhaps crucial to note that I am employing the term “queer,” which has been utilized in many ways across multiple disciplines, in a two-pronged sense, both in terms of the director’s homosexuality, reflected in the identity politics of many of his films, and to illustrate how his work deviates from the formal and cultural concerns of his cinematic contemporaries.

This queerness—the neither/nor quality—might help account for why Davies, despite the acclaim with which nearly all of his works have been met and the place of honor to which he has ascended in the annals of contemporary British cinema (he’s “regarded by many as Britain’s greatest living film director,” wrote the London Evening Standard’s Nick Roddick in 2008), remains understudied at serious length; meanwhile, he has historically had difficulty getting official funding for his projects from governmental arts councils, further contributing to his status as an industry outsider. Various chapters in both popular and more academically oriented film-studies anthologies have been devoted to him over the past two decades, but Wendy Everett’s invaluable Terence Davies (2001) for the Manchester University Press series British Film Makers remains the only previous existing English-language book-length study of the director’s work. The reason for what is surely a critical oversight cannot simply be Davies’s relatively small output: the seven features he has made at the time of this writing puts him in the same general category as such world-cinematic titans as Terrence Malick (six films), Andrei Tarkovsky (seven), Wong Kar-wai (ten), and Stanley Kubrick (thirteen), all known for the extended length of time they take between projects, and all subjects of numerous published critical studies—and all of them, like Davies, evincing a clear aesthetic unity across their oeuvres. And neither can Davies’s essential invisibility in the U.S. academic press be due to a matter of stateside inaccessibility, as his works were all at one time or another afforded distribution from major independent companies, theatrically and on home video.

Rather, I would argue that the reason for the lack of widespread scholarly analysis of Davies’s works is due to the difficulty of their unfashionably personal, contradictory queer natures, as well as the odd detachment with which they uncover deeply emotional states of being. A 1990 article by the U.S. critic Jonathan Rosenbaum in the British magazine Sight & Sound testifies to the inability of Davies’s 1988 feature Distant Voices, Still Lives to connect with American audiences: “It was probably the relative absence of plot—the ne plus ultra of commercial filmmaking— that deprived the movie of the larger audience it could and should have had, even if this absence permits a wholeness and an intensity to every moment that is virtually inaccessible to narrative filmmaking” (“Are You Having Fun?” 99). The dramatic outlines of Davies’s most personal films are universally relatable, but the abstractness with which he lays bare and interprets his traumas on the screen makes them opaque, even alien. Despite his most typical works being seemingly based in a recognizable idiom (broadly, the personal-memory film), they are not entirely legible as such. Upon deeper analysis, his films become puzzling works that skirt the lines between autobiography and fantasy, reality and fiction, radicalism and conservatism—each of those, incidentally, categories in which critics and academics prefer to place films.

Though his films have been explored at eloquent and revealing length in Everett’s book, I aim to focus more on the distinct emotional quandaries these films evoke in the viewer and to propose that their tonal and political in-betweenness is a form of cinematic queering. Through my exploration of their contradictions in the sections that follow, I will suggest that these films function within seemingly recognizable generic parameters only to then explode and thus queer conventional notions of narrative cinema. Whereas Everett’s book took the form of a chronological study of the director’s work, I am more interested in teasing out the connections and cross-references between his films in a less linear, more holistic fashion. Furthermore, Everett’s volume, published in 2001, necessarily could not have dealt with Davies’s two most recent films, Of Time and the City and The Deep Blue Sea, rich and significant texts that further elucidate the tenor and subtext of the director’s entire oeuvre, while also moving him into new realms (broadly, documentary and melodrama). Also, in focusing on what I see as the central paradoxes of Davies’s films, I will attempt to imply a more specifically queer reading than Everett had, to impart a sense that all of his seemingly opposed aesthetic and ideological cinematic traits work in surprising tandem to create a radical portrait of a fractured gay identity.

I aim not simply to delve into the textually or even subtextually gay aspects or details of the films but rather to propose that, in their entirety, and in the odd juxtapositions that fasten them together, they are imbued with—and perhaps defined by—a queer sensibility. Davies’s homosexuality—a source of anguish for him—is not merely incidental to any of these films, even those that elide any explicit reference to same-sex desire. These matters are also not so easy to parse. There are a variety of dimensions to Davies’s highly modernist queer aesthetic, and they are at turns related to desire, identity, politics, and time. For instance, alongside his impulse toward autobiography seems to sit a drive for self-negation; he’s inviting us to share his dreams and fears and privileging us to witness approximations of his past experiences, yet at the same time disallowing simple emotional readings of those experiences by foregrounding his own perspective as that of an outsider, a stranger in a strange land of his own making. Such aesthetics connect to one of the most essential aspects of Davies’s queerness: his status as a social outcast, a position related, variously, to his sexuality, his placement within (but mostly outside of) the mainstream film industry, and his devotion to outmoded pop-cultural signifiers, the traces of which appear in all of his films, often giving them the sense of emanating from an earlier—and, crucially, politically unfashionable—time and place.

With their constant tonal negotiations, Davies’s films exist in a curious space between fondness for the past and fear of it, a positioning that makes us aware of the social exclusion that the director felt as both an adolescent and as a formerly sexually active adult (Davies claims to be celibate today), which is a defining feeling of queerness. As a result, Davies, a filmmaker particularly preoccupied with the representation of time in cinema, carves out a peculiar, queer temporality, locating his films in a space that exists outside of the flow of culturally sanctioned, positively identified, procreatively fueled “normal time.” Time itself is reconstituted in Davies’s cinema, whether fragmented or slowed down, either outpacing or trailing behind social norms; the inexorable pull of forward motion butts heads with a nagging, unavoidable emotional and physical stasis.

Aesthetically, Davies’s queerness can be located in a series of distancing strategies that effectively put us viewers, and Davies, at a remove from the narratives, so that we are like Davies when he says, “I always felt as though I were a spectator” (qtd. in Everett 217). This is achieved through, variously and not exclusively, discordant sound-image combinations, hyperst...