- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Avital Ronell has put together what must be one of the most remarkable critical oeuvres of our era… Zeugmatically yoking the slang of pop culture with philosophical analysis, forcing the confrontation of high literature and technology or drug culture, Avital Ronell produces sentences that startle, irritate, illuminate. At once hilarious and refractory, her books are like no others."--Jonathan Culler, Diacritics

For twenty years Avital Ronell has stood at the forefront of the confrontation between literary study and European philosophy. She has tirelessly investigated the impact of technology on thinking and writing, with groundbreaking work on Heidegger, dependency and drug rhetoric, intelligence and artificial intelligence, and the obsession with testing. Admired for her insights and breadth of field, she has attracted a wide readership by writing with guts, candor, and wit.

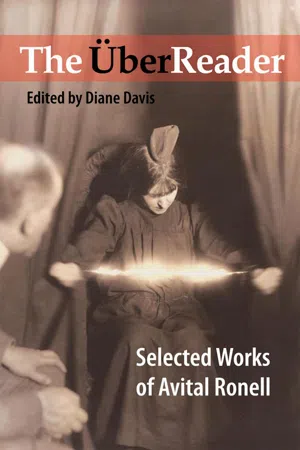

Coyly alluding to Nietzsche's "gay science," The ÜberReader presents a solid introduction to Avital Ronell's later oeuvre. It includes at least one selection from each of her books, two classic selections from a collection of her early essays (Finitude's Score), previously uncollected interviews and essays, and some of her most powerful published and unpublished talks. An introduction by Diane Davis surveys Ronell's career and the critical response to it thus far.

With its combination of brevity and power, this Ronell "primer" will be immensely useful to scholars, students, and teachers throughout the humanities, but particularly to graduate and undergraduate courses in contemporary theory.

For twenty years Avital Ronell has stood at the forefront of the confrontation between literary study and European philosophy. She has tirelessly investigated the impact of technology on thinking and writing, with groundbreaking work on Heidegger, dependency and drug rhetoric, intelligence and artificial intelligence, and the obsession with testing. Admired for her insights and breadth of field, she has attracted a wide readership by writing with guts, candor, and wit.

Coyly alluding to Nietzsche's "gay science," The ÜberReader presents a solid introduction to Avital Ronell's later oeuvre. It includes at least one selection from each of her books, two classic selections from a collection of her early essays (Finitude's Score), previously uncollected interviews and essays, and some of her most powerful published and unpublished talks. An introduction by Diane Davis surveys Ronell's career and the critical response to it thus far.

With its combination of brevity and power, this Ronell "primer" will be immensely useful to scholars, students, and teachers throughout the humanities, but particularly to graduate and undergraduate courses in contemporary theory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The UberReader by Avital Ronell, Diane Davis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatura & Crítica literaria. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Call of Technology

| Q. | Would you characterize your approach to technology as posthumanist? | |

| A. | Yes, I certainly would, though I might have to pause and explicate the meaning of “post.” Still, I look to technology to affirm those aspects of posthumanism that are more liberatory and politically challenging to us. As I said, one of my concerns has been with television. Beyond the thematizations of crime, murder, and the production of corpses that don’t need to be mourned, I am very interested in the way television stages and absorbs trauma, the way it puts in crisis our understanding of history and the relation of memory to experience. All of these aspects of the televisual that I have tried to read, as you indicate, presuppose a posthumanist incursion into these fields or presume that a posthumanist incursion has been made by these technological innovations (or philosophemes, as I like to call them). On a terribly somber note, I don’t see how, after Auschwitz, one can be a humanist. | |

| My work has concerned itself with the Nazi state as the first technologically constellated polity as well as with the fact that technology is irremissible. Mary Shelley projected this view of technology with her massive, monumental, commemorative work on the technobody, which was the nameless monster. The problem with (or opening for) technology is that no one is or can stay behind the wheel, finally, and no one is in charge. And the way I have tried to route and circuit the thinking of technology—indeed, in a posthumanist frame—exposes the extent to which it belongs to the domain of testing. This view has little to do with hubristic humanist assumptions…. | ||

| Technology has produced different registers of being, or is reflective of different registers of being, and even our rhetoric of desire has been steadily technologized. We say we’re “turned on,” we’re “turned off,” and so on. We also say we “had a blast,” which indicates a nuclear desire in desire. Nonetheless, there are different protocols of marking experience, and to arrive at some sensible reading of those protocols, one should no longer be tethered irrevocably to humanist delusions—delusions for which I have the greatest respect, of course. But humanism often functions like a drug that one really ought to get off of in order to be politically responsible. I think it is irresponsible not to be Nietzschean in this sense of risking the greatest indecency, of crossing certain boundaries that have seemed safe and comfortable and are managed at best by general consensus. Posthumanism is not necessarily popular with those who hold the moral scepter at this point. But I think it would be regressive and cowardly to proceed without rigorously interrogating humanist projections and propositions. It would be irresponsible not to go with these irreversible movements, or “revelations of being,” so to speak. That sounds a little irresponsible, too, since it’s a citation of Heidegger. But that’s just it: one is precisely prone to stuttering and stammering as one tries to release oneself from the captivity of very comfortable and accepted types of assignments and speech. An incalculable mix of prudence and daring is called for. | ||

| From “Confessions of an Anacoluthon” (258–59). | ||

1

Delay Call Forwarding

And yet, you’re saying yes, almost automatically, suddenly, sometimes irreversibly. Your picking it up means the call has come through. It means more: you’re its beneficiary, rising to meet its demand, to pay a debt. You don’t know who’s calling or what you are going to be called upon to do, and still, you are lending your ear, giving something up, receiving an order. It is a question of answerability. Who answers the call of the telephone, the call of duty, and accounts for the taxes it appears to impose?

The project of presenting a telephone book belongs to the anxiety registers of historical recounting. It is essentially a philosophical project, although Heidegger long ago arrested Nietzsche as the last philosopher. Still, to the extent that Nietzsche was said to philosophize with a hammer, we shall take another tool in hand, one that sheds the purity of an identity as tool, however, through its engagement with immateriality and by the uses to which it is put: spiritual, technical, intimate, musical, military, schizonoid, bureaucratic, obscene, political. Of course a hammer also falls under the idea of a political tool, and one can always do more than philosophize with it; one can make it sing or cry; one can invest it with the Heideggerian cri/écrit, the Schreiben/Schrei of a technical mutation. Ours could be a sort of tool, then, a technical object whose technicity appears to dissolve at the moment of essential connection.

When does the telephone become what it is? It presupposes the existence of another telephone, somewhere, though its atotality as apparatus, its singularity, is what we think of when we say “telephone.” To be what it is, it has to be pluralized, multiplied, engaged by another line, high strung and heading for you. But if thinking the telephone, inhabited by new modalities of being called, is to make genuinely philosophical claims—and this includes the technological, the literary, the psychotheoretical, the antiracist demand—where but in the forgetting of philosophy can these claims be located? Philosophy is never where you expect to find it; we know that Nietzsche found Socrates doing dialectics in some backstreet alley. The topography of thinking shifts like the Californian coast: “et la philosophie n’est jamais là où on l’attend,” writes Jean-Luc Nancy in L’oubli de la philosophie.1 Either it is not discoverable in the philosopher’s book, or it hasn’t taken up residence in the ideal, or else it’s not living in life, nor even in the concept: always incomplete, always unreachable, forever promising at once its essence and its existence, philosophy identifies itself finally with this promise, which is to say, with its own unreachability. It is no longer a question of a “philosophy of value,” but of philosophy itself as value, submitted, as Nancy argues, to the permanent Verstellung, or displacement, of value. Philosophy, love of wisdom, asserts a distance between love and wisdom, and in this gap that tenuously joins what it separates, we shall attempt to set up our cables.

Our line on philosophy, always running interference with itself, will be accompanied no doubt by static. The telephone connection houses the improper. Hitting the streets, it welcomes linguistic pollutants and reminds you to ask, “Have I been understood?” Lodged somewhere among politics, poetry, and science, between memory and hallucination, the telephone necessarily touches the state, terrorism, psychoanalysis, language theory, and a number of death-support systems. Its concept has preceded its technical installation. Thus we are inclined to place the telephone not so much at the origin of some reflection but as a response, as that which is answering a call.

Perhaps the first and most arousing subscribers to the call of the telephone were the schizophrenics, who created a rhetoric of bionic assimilation—a mode of perception on the alert, articulating itself through the logic of transalive coding. The schizophrenic’s stationary mobility, the migratory patterns that stay in place offer one dimension of the telephonic incorporation. The case studies which we consult, including those of the late nineteenth century, show the extent to which the schizo has distributed telephone receivers along her body. The treatment texts faithfully transcribe these articulations without, however, offering any analysis of how the telephone called the schizophrenic home. Nor even a word explaining why the schizo might be attracted to the carceral silence of a telephone booth.

But to understand all this we have had to go the way of language. We have had to ask what “to speak” means. R. D. Laing constructs a theory of schizophrenia based, he claims, on Heidegger’s ontology, and more exactly still, on Heidegger’s path of speech, where he locates the call of conscience. This consideration has made it so much the more crucial for us to take the time to read what Heidegger has to say about speaking and calling, even if he should have suspended his sentences when it came to taking a call. Where Laing’s text ventrilocates Heidegger, he falls into error, placing the schizo utterance on a continent other than that of Heidegger’s claims for language. So, in a sense, we never leave Heidegger’s side, for this side is multifaceted, deep and troubling. We never leave his side but we split, and our paths part. Anyway, the encounter with Laing has made us cross a channel.

Following the sites of transference and telephonic addiction we have had to immigrate in this work to America, or more correctly, to the discourse inflating an America of the technologically ghostless above. America operates according to the logic of interruption and emergency calling. It is the place from which Alexander Graham Bell tried to honor the contract he had signed with his brother. Whoever departed first was to contact the survivor through a medium demonstrably superior to the more traditional channel of spiritualism. Nietzsche must have sensed this subterranean pact, for in the Genealogy of Morals he writes of a telephone to the beyond. Science’s debt to devastation is so large that I have wanted to limit its narrative to this story of a personal catastrophe whose principal figures evolved out of a deceased brother. Add to that two pairs of deaf ears: those of Bell’s mother and his wife, Mabel Bell.

Maintaining and joining, the telephone line holds together what it separates. It creates a space of asignifying breaks and is tuned by the emergency feminine on the maternal cord reissued. The telephone was borne up by the invaginated structures of a mother’s deaf ear. Still, it was an ear that placed calls, and, like the probing sonar in the waters, it has remained open to your signals. The lines to which the insensible ear reconnects us are consternating, broken up, severely cracking the surface of the region we have come to hold as a Book.

Even so, the telephone book boldly answers as the other book of books, a site which registers all the names of history, if only to attend the refusal of the proper name. A partial archivization of the names of the living, the telephone book binds the living and the dead in an unarticulated thematics of destination. Who writes the telephone book, assumes its peculiar idiom or makes its referential assignments? And who would be so foolish as to assert with conviction that its principal concern lies in eliciting the essential disclosure of truth? Indeed, the telephone line forms an elliptical construction that does not close around a place but disperses the book, takes it into the streets, keeping itself radically open to the outside. We shall be tightroping along this line of a speculative telephonics, operating the calls of conscience to which you or I or any partially technologized subject might be asked to respond.

The Telephone Book, should you agree to these terms, opens with the somewhat transcendental predicament of accepting a call. What does it mean to answer the telephone, to make oneself answerable to it in a situation whose gestural syntax already means yes, even if the affirmation should find itself followed by a question mark: Yes?2 No matter how you cut it, on either side of the line, there is no such thing as a free call. Hence the interrogative infection of a yes that finds itself accepting charges.

To the extent that you have become what you are, namely, in part, an automatic answering machine, it becomes necessary for questions to be asked on the order of, Who answers the call of the telephone, the call of duty, or accounts for the taxes it appears to impose? Its reception determines its Geschick, its destinal arrangement, affirming that a call has taken place. But it is precisely at the moment of connection, prior to any proper signification or articulation of content, that one wonders, Who’s there?

Martin Heidegger, whose work can be seen to be organized around the philosophical theme of proximity, answered a telephone call. He gave it no heed, not in the terms he assigned to his elaborations of technology. Nor did he attempt in any way to situate the call within the vast registers of calling that we find in Being and Time, What Is Called Thinking?, his essays on Trakl or Hölderlin, his Nietzsche book. Heidegger answered a call but never answered to it. He withdrew his hand from the demand extended by a technologized call without considering whether the Self which answered that day was not occupied by a toxic invasion of the Other, or “where” indeed the call took place. We shall attempt to circumscribe this locality in the pages that follow. Where he put it on external hold, Heidegger nonetheless accepted the call. It was a call from the SA Storm Trooper Bureau.

Why did Heidegger, the long-distance thinker par excellence, accept this particular call, or say he did? Why did he turn his thought from its structure or provenance? Averting his gaze, he darkens the face of a felt humanity: “man is that animal that confronts face to face” (I, 61). The call that Heidegger did but didn’t take is to take its place—herein lies the entire problematic: where is its place, its site and advent? Today, on the return of fascism (we did not say a return to fascism), we take the call or rather, we field it, listening in, taking note. Like an aberrant detective agency that maps our empirical and ontological regions of inquiry, we trace its almost imperceptible place of origin. Heidegger, like the telephone, indicates a structure to which he has himself only a disjunctive rapport. That is to say, both the telephone and Martin Heidegger never entirely coincide with what they are made to communicate with; they operate as the synecdoches of what they are. Thus Heidegger engineers the metonymical displacements which permit us to read National Socialism as the supertechnical power whose phantasms of unmediated instantaneity, defacement, and historical erasure invested telephone lines of the state. These lines are never wholly spliced off from the barbed wires circumscribing the space of devastation; calls for execution were made by telephone, leaving behind the immense border disturbances of the oral traces which attempt to account for a history. Hence the trait that continues to flash through every phone call in one form or another, possessing characteristics of that which comes to us with a receipt of acknowledgment or in the hidden agency of repression: the call as decisive, as verdict, the call as death sentence. One need only consult the literatures trying to contain the telephone in order to recognize the persistent trigger of the apocalyptic call. It turns on you: it’s the gun pointed at your head.

This presents the dark side of the telephonic structure. Kafka had already figured it in The Trial, The Castle, “The Penal Colony,” “My Neighbor.” The more luminous sides—for there are many—of grace and reprieve, for instance, of magical proximities, require one to turn the pages, or perhaps to await someone else’s hand. Take Benjamin’s hand, if you will, when he, resounding Bell, names the telephone after an absent brother (“mein Zwillingsbruder”). The telephone of the Berlin childhood performed the rescue missions from a depleted solitude: Den Hoffnungslosen, die diese schlechte Welt verlassen wollte, blinkte er mit dem Licht der letzten Hoffnung. Mit den Verlassenen teilte er ihr Bett. Auch stand er im Begriff, die schrille Stimme, die er aus dem Exil behalten hatte, zu einem warmen Summen abzudämpfen.3 So even if you didn’t catch the foreign drift, and the telephone has no subtitles, you know that the danger zone bears that which saves, das Rettende auch: calling back from exile, suspending solitude, and postponing the suicide mission with the “light of the last hope,” the telephone operates both sides of the life-and-death switchboard. For Benjamin, for the convict on death row, for Mvelase in Umtata.4 Let it be said, in conjunction with Max Brod’s speculations, that the telephone is double-breasted, as it were, circumscribing itself differently each time, according to the symbolic localities marked by the good breast or the bad breast, the Kleinian good object or bad object. For the telephone has also flashed a sharp critique at the contact taboos legislated by racism. We shall still need to verify these lines, but let us assume for now that they are in working order and that the angel’s rescue is closely tied to the pronouncement of killer sentences.

Just as Heidegger, however, by no means poses as identical to that for which he is made to stand—as subject engaged on the lines of National Socialism—so the telephone, operating as synecdoche for technology, is at once greater and lesser than itself. Technology and National Socialism signed a contract; during the long night of the annihilating call, they even believed in each other. And thus the telephone was pulled into the districts of historical mutation, making epistemological inscriptions of a new order, while installing a scrambling device whose décryptage has become our ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART I The Call of Technology

- PART II Freedom and Obligation

- PART III Psyche–Soma

- PART IV Danke! et Adieu

- PART V The Fading Empire of Cognition

- Index