eBook - ePub

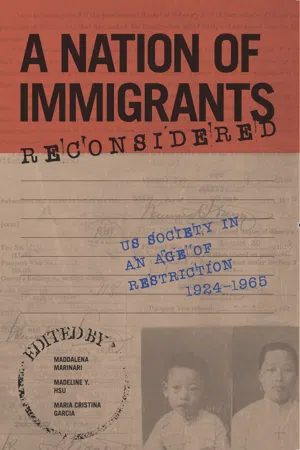

A Nation of Immigrants Reconsidered

US Society in an Age of Restriction, 1924-1965

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Nation of Immigrants Reconsidered

US Society in an Age of Restriction, 1924-1965

About this book

Scholars, journalists, and policymakers have long argued that the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act dramatically reshaped the demographic composition of the United States. In A Nation of Immigrants Reconsidered, leading scholars of immigration explore how the political and ideological struggles of the "age of restriction"--from 1924 to 1965--paved the way for the changes to come. The essays examine how geopolitics, civil rights, perceptions of America's role as a humanitarian sanctuary, and economic priorities led government officials to facilitate the entrance of specific immigrant groups, thereby establishing the legal precedents for future policies. Eye-opening articles discuss Japanese war brides and changing views of miscegenation, the recruitment of former Nazi scientists, a temporary workers program with Japanese immigrants, the emotional separation of Mexican immigrant families, Puerto Rican youth's efforts to claim an American identity, and the restaurant raids of conscripted Chinese sailors during World War II.

Contributors: Eiichiro Azuma, David Cook-Martín, David FitzGerald, Monique Laney, Heather Lee, Kathleen López, Laura Madokoro, Ronald L. Mize, Arissa H. Oh, Ana Elizabeth Rosas, Lorrin Thomas, Ruth Ellen Wasem, and Elliott Young

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Nation of Immigrants Reconsidered by Maddalena Marinari, Madeline Hsu, Maria Cristina Garcia, Maddalena Marinari,Madeline Hsu,Maria Cristina Garcia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Immigration Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Illinois PressYear

2018Print ISBN

9780252083969, 9780252042218eBook ISBN

9780252050954PART I

Policy and Law

The chapters in the first section of the book focus on the intersections between immigration policy and US international history. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, US legislators, in response to the largest global migration in world history, wrested immigration policy away from state powers and centralized immigration control, but they also placed parts of immigration enforcement in the hands of consular offices, shipping companies, and authorities in sending countries. From the very beginning then, immigration policy, usually presented as an instrument of domestic policy, was profoundly intertwined with US foreign policy and international developments.

Challenging the traditional periodization of immigration control, Elliott Young traces the long history of remote control practices—such as medical inspections, visas, and passports—and their long-term repercussions for sending and receiving nations from the late nineteenth century to the present. Young also shows how remote control affected all immigrants, even those from the Americas who were exempted from the harsher provisions of the 1924 Immigration Act. For example, while American growers and other businesses actively recruited Mexican labor, immigration officials still found ways to curtail their entry because Mexicans did not conform to policymakers’ notions of ideal workers and citizens.

Expanding on Young’s argument that the success of restrictive US immigration policy depended heavily on international cooperation, Kathleen López explores the impact of US immigration restriction on the Caribbean. She powerfully shows how a major unintended consequence of the new quota system in the United States was the diversion of migrants to countries with less restrictive immigration policies in the Caribbean and Latin America. Immigrants from eastern Europe, for example, traveled in large numbers to Cuba, where some strategically tried to acquire Cuban citizenship and later migrate to the United States as non-quota immigrants. Others paid smugglers to transport them across the short stretch of ocean that separated Cuba from the United States. In response to these developments, the federal government encouraged steamship companies to collaborate in the policing of the high seas to capture smugglers and their human contraband. The United States also pressured countries to adopt more restrictive immigration policies to keep “undesirables” out of the hemisphere. Developing countries like Cuba acquiesced because immigration gatekeeping was a symbol of modernism and created leverage with the United States, its major economic market.

Although the commitment to immigration restriction remained strong throughout the entire period covered in this anthology, the outbreak of World War II and the geopolitical order that emerged with the onset of the Cold War forced legislators to reconsider and amend, at least superficially, the country’s immigration policy. These changing foreign policy priorities provided an opening for supporters of immigration to push for a more humane immigration system. Laura Madokoro examines how the refugee crises of the 1940s and 1950s presented Americans with a moral dilemma. In response to hundreds of thousands of people uprooted by war and revolution around the world, many Americans argued that their country, as the new world leader, had a humanitarian obligation to assist refugees and other displaced persons. Sensing an opening, religious and secular humanitarians emphasized the benefits of refugee admissions for the US economy and international relations, but they faced resistance from restrictionists in Congress who fought hard to maintain the status quo. The tension between those who supported an international vision of immigration policy and those who argued that immigration was the purview of domestic policy produced mixed policy results. Pro-refugee legislators succeeded in pushing for piecemeal legislation that allowed several hundred thousand refugees (mostly European) to relocate to the United States. They also succeeded in carving out a small refugee quota in the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, but it would not be until 1980 that Congress passed more comprehensive refugee legislation.

By looking at the international debates about immigration restriction, David Cook-Martín and David FitzGerald challenge yet another assumption about the reasons behind the passage of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act. While the authors do not deny that the language of Cold War civil rights contributed to the push for immigration reform in 1965, they argue that critical geopolitical developments in the Western Hemisphere influenced the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act just as deeply. By focusing on the elimination of restrictive immigration laws in Latin American countries, they demonstrate that the passage of the 1965 act was part of larger regional efforts to reduce racialized laws. The authors’ discussion of the influence of Latin American countries in debates over immigration policy in the United States underscores the need for a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between the United States and its neighbors. They also provide a fresh perspective on the role that foreign policy played in the passage of the act as much of the existing scholarship focuses on the role that US interests in Asia and Africa played during the debates over immigration reform.

CHAPTER 1

Beyond Borders

Remote Control and the Continuing Legacy of Racism in Immigration Legislation

Don’t you see that the man who comes here selects us, And that is what causes our worry and fuss: Our selection of aliens should begin over sea. And not when they enter this land of the free.

—Terence Powderly, Grand Master of Knights of Labor and Commissioner General of Immigration (1892–1902)

It is much easier to refuse a visa than to deny admittance to the suspected person after he has arrived at a port of entry of the United States.

—Secretary of State Robert Lansing to President Woodrow Wilson, August 20, 1919

Controlling immigration to the United States became effective in the 1920s only when the government learned how to stop migrants before they left their home countries, but the US government tried to develop a system of remote control long before that. Immigration authorities created a system of medical inspections, visas, and passports that turned consular offices and shipping companies into frontlines for immigration enforcement. By the 1920s, these extraterritorial boundaries became the most significant obstacle to entry, more daunting for immigrants than the inspection checkpoints at US ports of entry. These overseas inspections could prevent migrants from departing their home countries and thus control immigration flows far more effectively. That the United States secured this international cooperation reflected its growing influence around the world. These practices were not solely a symbol of US imperial reach, however, but of an expanding global system of border security and migration control. Concerns over national security and the regulation of borders pushed countries to enforce migration laws by what political scientist Aristide Zolberg calls “remote control.”1

Remote control refers to the practices and mechanisms to enforce immigration policy beyond the nation’s borders as well as the efforts to outsource enforcement to private companies. Reliance on private companies has expanded and contracted since the late nineteenth century, but the overall trend has been toward greater direct government control over immigration enforcement. While pushing private companies to enforce immigration laws may be read as a sign of state power, it also reflects the inability of the state to enforce its own regulations. As Adam McKeown shows in Melancholy Order, the US government’s efforts to gain control over the visa and documentation process in China, where it first became a regular practice in the mid-nineteenth century, were continuously undermined by Chinese officials and private entrepreneurs.2 The aim of extraterritorial migration control was to be able to track migrants and to distinguish between citizens, legal residents, and inadmissible aliens before they even boarded ships or trains. Passports and other letters of introduction have a longer history, but until there was a centralized state bureaucracy to standardize these documents, they were not useful for tracking and regulating mobility.3 Remote control through medical inspections and certificates of residency for Chinese were thus the primary mechanisms to regulate movement before the standardization of the passport during World War I. By the time of the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, remote-control practices had become institutionalized through consulates that were responsible for sorting and selecting immigrants based on national quotas.

Historians of migration who still see the world through national lenses focus on what happens once migrants reach a port of entry. A transnational perspective that allows us to see the entire migratory circuit reveals that exclusion occurs more often before migrants leave their home countries or in third-countries surrounding the intended destination. The extraterritorial enforcement of immigration restrictions emerged in the nineteenth century as a way for countries to keep undesirable migrants from their shores. From World War I through the 1920s, this system of remote control solidified through the internationalization and regimentation of a regime of passports and visas that has now become standard practice around globe. Although the United States was at the forefront in establishing a robust immigration bureaucracy in the late nineteenth century, it was by no means the only country to erect immigration restrictions. The cooperation of countries in controlling the movement of people was a new way of recognizing the sanctity of national boundaries and national sovereignty. While the United States coaxed other countries to comply with its restrictions, those countries often resisted US demands or had their own reasons for implementing restrictionist policies. The global system of migration restriction put in place in the 1920s emerged out of these earlier efforts. The pre- and post-1920s era of migration restriction are inextricably linked and the two periods cannot and should not be seen as distinct phases in US immigration policy history.

Enlisting private transport companies to enforce migration restrictions was central to the emerging new order. From the nineteenth century through the 1920s, the relationship between private transport companies and governments waxed and waned. Although the early outsourcing of inspections in the 1860s and 1870s reflected the inability of government inspectors to get the job done, by the 1920s, the US immigration bureaucracy was robust enough to conduct its own inspections and demand compliance by private companies. The regularization of travel documents and the professionalization of the Foreign Service in the 1920s helped the United States government to gain control over what previously had been a fairly chaotic system of inspections and haphazard travel permissions. It is not a coincidence that the national-origins quota acts emerged in the 1920s. Without a vigorous remote-control bureaucracy in place, it would have been impossible to sort through millions of immigrants before they arrived on US shores.

Migration and borderlands scholars have explored exclusions at the borderline, but they have paid short shrift to the bureaucratic mechanisms of extraterritorial immigration control.4 The large number of migration books with “fence” or “gate” in the title suggests an emphasis on the physical bound...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I. Policy and Law

- Part II. Labor

- Part III. “Who is a Citizen? Who Belongs?”

- Afterword: The Black Presence in US Immigration History

- Contributors

- Index