eBook - ePub

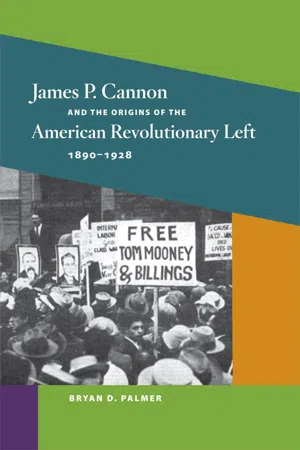

James P. Cannon and the Origins of the American Revolutionary Left, 1890-1928

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

James P. Cannon and the Origins of the American Revolutionary Left, 1890-1928

About this book

Bryan D. Palmer's award-winning study of James P. Cannon's early years (1890-1928) details how the life of a Wobbly hobo agitator gave way to leadership in the emerging communist underground of the 1919 era. This historical drama unfolds alongside the life experiences of a native son of United States radicalism, the narrative moving from Rosedale, Kansas to Chicago, New York, and Moscow. Written with panache, Palmer's richly detailed book situates American communism's formative decade of the 1920s in the dynamics of a specific political and economic context. Our understanding of the indigenous currents of the American revolutionary left is widened, just as appreciation of the complex nature of its interaction with international forces is deepened.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access James P. Cannon and the Origins of the American Revolutionary Left, 1890-1928 by Bryan D. Palmer in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9780252092084Subtopic

Political Biographies | 1 Rosedale Roots: Facts and Fictions |

An American Birth

11 February 1890: A boy child is born in the working-class hamlet of Rosedale, Kansas. Childbirth does not occasion a great deal of fanfare in the poor industrial districts of the Greater Kansas City region, where Rosedale is situated adjacent to both of the Kansas and Missouri cities of the same name. In most working-class households, deliveries take place at home, rather than in a hospital. Neighbors help, large families rally, and a midwife undoubtedly attends at this Rosedale birth. The physician’s role is almost certainly minimal, perhaps limited to reporting that a child has come safely into the world. However, even that level of involvement is unlikely, and no birth certificate is required to register the baby before the rather unwatchful eyes of the late nineteenth-century state.1

The parents of this newborn are recently arrived in the United States of America. The son they celebrate on this midwinter day will be as American as they are striving successfully to become. For certain “white ethnics” such as they, ultimate acculturation at this point in United States history is less a matter of citizenship’s socially learned or politically bestowed credentials and more a reality of birthplace.

This is a native son who will carry his proletarian heritage, admittedly something of a choice, into the twentieth century. There it will rub up against the dominance of hegemonic powers in ways that persistently exhibit frictions and tensions: of the promise of equality tempered by injustice and material deprivation; of the lure and lore of family, so often constrained by want and need, the ties likely to be lost temporarily in the chaos of survival struggles; of labor and capital, contextualized in an ongoing battle where rural and urban mesh as development proceeds with a vehement unevenness; of a consciousness of belonging, cut to the bone by the displacements of being ever alien. The boy born with and socialized through this legacy of ambivalence will be a mix of the old and the new. He will, throughout his life, embrace orthodoxy and tradition as well as make deep commitments to fundamental change. Leaving Rosedale as a young man, this product of small-town Kansas will become an habitué of the metropolitan center (Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles), a revolutionary in a society long distanced from its eighteenth-century origins in revolution. A native son he was born, however, and a native son he would remain. This Rosedale boy is James Patrick Cannon.2

Fin de Siècle Context: Kansas in a World of Change

The 1890s, in which the infant Jim Cannon would grow to boyhood, was a period of profound destabilization. Cannon’s birthplace, the United States, emerged as a pivotal power, becoming the premier industrial-capitalist nation in the world in 1894, turning out fully one-third of the recorded product of the globe. The business cycle nevertheless took a turn for the worse in the early 1890s; the state was challenged forcefully by an army of unruly tramps, and found itself seduced by a presidential pretender of populist persuasion. Strikes rocked the relations of capital and labor. Before his fifth birthday, a Rosedale boy would have heard talk of shootings at Carnegie’s Homestead works; the pardoning of some of the Haymarket martyrs; and the infallible, salvation-like authority of Eugene Debs, who led American railwaymen—quintessential workers of the age—on a justice crusade for the laboring classes.3 It was a time of trouble; it was a time of hope.4

The Kansas in which James Patrick Cannon was born was somewhat unusual. Nonetheless, it too was ravaged by change in the late nineteenth and very early twentieth centuries. The Greater Kansas City region, encompassing the border cities of Kansas City, Missouri, Kansas City, Kansas, and the adjoining enclaves of Independence, Missouri, and Rosedale, Kansas, had a history reaching back to the fur-trade era.5 However, its dynamic growth was in the post-1860 period of economic expansion associated with the coming of railroads, and, most emphatically, the explosive upsurge of manufacturing that developed out of the 1880s and the depression of the 1890s. Productive output was paced by the meatpacking and grain/flour milling enterprises that drew on the livestock and crops of the surrounding agricultural hinterland, but leavened by coal mining and other, more obviously industrial, activity. The value of that output soared from roughly $6 million in 1890 to more than $218 million twenty years later. Located near the confluence of the Missouri and Kansas Rivers, straddling the state line, the Greater Kansas City area encompassed a territory of slightly more than seventy-five square miles in 1915: an area traversed by 25 percent of the nation’s rail lines, which linked the district to every major metropolitan center in the United States. Booster publications proclaimed the Greater Kansas City region to be “The Heart of America.”6

Yet the early heart of industrial-capitalist America could be cold indeed. In the early to mid-1880s, years of abundant rainfall sustained bumper crops in the Midwest. As railway fever added heat to the soaring land market, a speculative mania gripped town and country alike, driving property values upward in an inflationary cycle that fueled illusions of never-ending prosperity. Then, as suddenly as it had expanded, the bubble burst. Kansas was hit hard by a decade of declining rainfall, commencing in 1887–1888, and dry conditions were exacerbated by summers of scorching heat and moisture-robbing winds from the south. Crop yields declined and then shriveled to insignificance, land prices bottomed out, and many farmers faced foreclosure and destitution; 60 percent of the taxable acreage of the state was encumbered in 1890. Some eked out a marginal existence, but others gave up, their stoic resignation articulated in a stream of covered wagons heading out of the state with Conestoga canvas billowing the words, “In God we trusted, in Kansas we busted.”7

What nature missed in its ravaging of the land, the financial institutions wanted to seize. Railroads, bankrolled by municipal and state taxes, began to raise their freight rates, which had originally protected local Kansas industry in diversified manufacturing sectors. Depression lowered over economic life in the early to mid-1890s. Particularly hard hit were a multitude of factories that existed in the shadows of large milling and meatpacking monopolies. Workplaces closed, unemployment rose, wages were cut back, living and working conditions deteriorated. Small wonder that Kansas was perhaps the core region of a United States populist revolt that raged against “the interests,” and was sustained by a movement culture of programs, parties, itinerant organizers, open-air meetings, dissident newspapers, and generalized hostility to the unbridled acquisitive individualism of the age.8

On 12 June 1890, when young Jim Cannon was barely five months old, Topeka, Kansas, was the site of a political convention. Attended by ninety delegates representing the Farmers’ Alliance, the Knights of Labor, the Farmers’ Mutual Benefit Association, the Patrons of Husbandry, single-taxers, greenbackers, and the stillborn Union Labor Party, the Topeka gathering founded the People’s Party. Their sights set on dethroning the reigning Republicans, the Kansas populists built coalitions, coaxed Democrats, and rallied the people. Out of the turmoil came Mary E. Lease, an indomitable Irish-American agitator who delivered 160 speeches in 1890 alone. Her reputed admonition, directed at the farmers of Kansas, to “raise less corn and more Hell,” was a rhetorical coup, but her passionate message echoed wider oppositional meanings.9 Two years later, Kansas voted the Wichita populist Lorenzo D. Lewelling into the governor’s mansion. Lewelling railed against the robbery and enslavement of the people, deploring conventional politics as little more “than a state of barbarism.”10 As one historian of Kansas populism concluded, during the 1890s “the state served as a stage upon which the rest of the nation acted out its antagonisms, hopes, and frustrations.”11

In the Shadow of the Irish Diaspora: England and America

For the Cannon family, Rosedale was this Kansas stage. It was not so much bounded by the nation as it was situated within movements and migrations of socioeconomic change associated with the English-speaking transatlantic world; at the same time, though, it was inhibited by a fundamental, and parochial, enclosure. One fragment of this process involved James Patrick Cannon’s parents: John Cannon and his second wife, Ann Hackett.12 Both were English-born children of Irish emigrants escaping the blight of the potato famine in the 1840s and 1850s. They coincidentally shared a common background in the English town of Bolton, where they were “city poor.”13 Bolton was a textile center of approximately 70,000 in 1860, associated with the traumatic changes of the Industrial Revolution.14

John Cannon was born on 14 January 1857 in nearby Chorley, a smaller enclave infamous for a riotous 1779 attack on one of the “dark, satanic mills” of early cotton-factory capitalism.15 At eleven years of age Cannon left school, working a few weeks in a cabinet-making shop (the occupation at which Ann’s father toiled), and later apprenticing four years with a tailor. Eventually he took up the trade of spindle flymaker,16 a craft displaced in the final wave of technological innovations that revamped the cotton industry in the years after midcentury.17 His apprenticeship being for nought, John Cannon settled, at the age of fifteen, for laboring jobs.

The industrial Lancashire in which Ann Hackett and John Cannon were raised was thus the archetypal locale of nineteenth-century proletarian immiseration. Over it rolled waves of intense labor-process transformation, orchestrated by powerful families of Tory mill owners.18 With much of an expanding population made up of the dispossessed Irish—half of Bolton’s population increase at mid-century came from in-migration—social dislocation rather than class solidarity was often dominant, with the attendant struggle of the state to manage various pathologies. Lancashire was thus scarred by the grim edifices and difficult adjustments of factory production and a range of regulatory welfare interventions, from the Poor Law to the institutionalization of modern policing and intrusive campaigns to improve the public health.19 A congested demography of urban poverty, an occupational degradation composed of equal parts craft dilution and industrial paternalism, and the subterranean subordinations of ethnicity thus marked Victorian Bolton as a way station for those mobile Irish and their acclimatized offspring quick to see opportunities to be had in distant lands.

At the age of nineteen John Cannon married, and in the space of five years he fathered three children with his young wife, Kate: Edward (1877), Mary (1879), and Thomas (1882). His most constant work was as a foundry laborer; one of his brothers was an iron worker. Next to his family, John’s consuming passion was the Bolton Irish Land League, where he served as secretary, organizing meetings and providing touring orators with a platform to denounce Irish oppression. John Cannon, a child of the Lancashire mill town, was nevertheless a convinced Irish Republican, a determined opponent of England’s colonizing oppressions.

John Cannon’s feet would never touch down on Irish soil, and even Bolton could not hold him long into adulthood. Work was seldom steady for any of the Cannon clan, and John’s father, a skilled tailor noted for the fine fit of the suits he made, struck out for New York City with his wife, Catherine. Lines of communication and knowledge of family members’ whereabouts and well-being were not always sure in the Cannon family circles, however. John Cannon departed for the United States in 1883, leaving Kate and the children behind in Bolton, thinking that he could make a better go of it in the new world that was now home to his father and mother. Upon arrival in New York, the Irish immigrant was disappointed to see his father living a wasted, dissolute life, in which drinking sprees were punctuated by periods of irregular return to tailoring. There was nothing for John, socially or economically, in the sprawling urban complexity of metropolitan enticements.

Making his way to the Providence, Rhode Island, vicinity, John Cannon reconnected with his foundry-working younger brother Jim; landed a job; and immersed himself in the local labor movement by joining the Knights of Labor (then at its peak) and becoming secretary of the Central Labor Council. A member of Prospect Assembly, No. 2971, a small Central Falls local of 38 carders and spinners in the mid-1880s, the congenial Cannon found the sociability of the Order attractive, especially in the period of separation from his family. He would be remembered by Providence radicals thirty years later, although his stint as a figure of note in labor-reform circles was brief. It is likely that John’s stature in the memory of Rhode Island’s working-class activists was enhanced by association with another Cannon, possibly John’s younger brother Jim, who may have been the John T. Cannon (Bolton-born in 1867) who figured prominently in Rhode Island Lodge, No. 147, of the International Association of Machinists (IAM), which he joined in 1897 and of which he was soon elected president. This Cannon also played an active role in the American Federation of Labor-dominated Central Trades and Labor Union of Rhode Island, and was an outspoken advocate of labor-political action in the establishment of a 1902 Trades Union Economic League.20

His labor movement involvement facilitated by the absence of Kate and their children, John Cannon would apparently find family a brake on his later activity; he was destined not to play an ongoing role in the class struggles of the next decade. Nevertheless, his initial Providence/Central Falls sojourn, and involvement in the Knights of Labor/Central Labor Union, eased the newcomer’s adaptation to his adopted land. Having settled into Rhode Island life and labor, he sent for his wife and children, who probably arrived in the United States sometime in 1885. Barely reunited, tragedy soon befell the family: Kate died in 1886.21

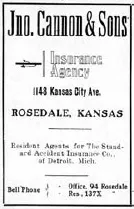

John Cannon’s brother Jim had married one of two Hackett sisters, both of whom, with their mother, had emigrated to the United States from Bolton. Family ties and Old-World familiarities, not to mention a common enthusiasm for the radicalism of Irish Home Rule, brought John Cannon and Ann Hackett together. The dire predicament of a working father responsible for three children under the age of ten may have enhanced the attractiveness of his brother’s sister-in-law for John Cannon. The couple married in 1887, eleven months after the death of Cannon’s first wife, and around the time that John Cannon offered a toast to “the ladies” at a February social and Knights of Labor dance. John’s mother, Catherine, either abandoned by her dissolute husband or liberated from responsibility for him by death or choice, moved west to Rosedale in this same period, drawn to Kansas because of the presence of four of her brothers, who had settled in Kansas City, Missouri, and nearby Shawnee County, within which Rosedale was situated. When word came that a large rolling mill or smelter might afford plenty of work, John Cannon and his brother Jim joined their mother and her brothers, moving across the country to partake of the economic bonanza that had drawn so many to the Midwest. Unfortunately, the Cannon exodus did not manage to catch even the tail-end of prosperity’s promise; its timing, in 1887, could not have been worse, coinciding as it did with an economic downturn that would last a decade. The metal-working factory failed and was converted to a small foundry. In what was by then an oft-repeated disappointment in the Irishman’s life, it afforded only casual employment and unskilled wages to John Cannon. His brother Jim likely returned in disillusionment to Rhode Island, joining the IAM as the nationwide depression lifted in 1897.22 Industrial Rosedale thus looked as much the bust in the late 1880s and early 1890s as the drought-plagued farms of Kansas. The ideas and resentment that fueled the region’s populist revolt found a ready reception in the Cannon household.

The Industrial Frontier

The Rosedale that drew so many Cannons to its environs in the mid- to late 1880s was but a step removed from what family members, driven by Irish destitution to the gritty slums of a mill town like Bolton, then later by constricted opportunities to the bustling metropolis of New York or the industrial sectors of Providence, must have regarded as a bucolic frontier. Originally plotted in 1872, Rosedale drew its name from the wild roses nestled in ravines...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Communist Can(n)on

- 1. Rosedale Roots: Facts and Fictions

- 2. Youth’s Discoveries

- 3. Hobo Rebel/Homeguard

- 4. Red Dawn

- 5. Underground

- 6. Geese in Flight

- 7. Pepper Spray

- 8. Stalinist Suspensions

- 9. Labor Defender

- 10. Living with Lovestone

- 11. Expulsion

- Conclusion: James P. Cannon, the United States Revolutionary Movement, and the End of an Age of Innocence

- Notes

- Index

- Illustrations