- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the early 1900s, workers from new U.S. colonies in the Philippines and Puerto Rico held unusual legal status. Denied citizenship, they nonetheless had the right to move freely in and out of U.S. jurisdiction. As a result, Filipinos and Puerto Ricans could seek jobs in the United States and its territories despite the anti-immigration policies in place at the time.

JoAnna Poblete's Islanders in the Empire: Filipino and Puerto Rican Laborers in Hawai'i takes an in-depth look at how the two groups fared in a third new colony, Hawai'i. Using plantation documents, missionary records, government documents, and oral histories, Poblete analyzes how the workers interacted with Hawaiian government structures and businesses, how U.S. policies for colonial workers differed from those for citizens or foreigners, and how policies aided corporate and imperial interests.

A rare tandem study of two groups at work on foreign soil, Islanders in the Empire offers a new perspective on American imperialism and labor issues of the era.

JoAnna Poblete's Islanders in the Empire: Filipino and Puerto Rican Laborers in Hawai'i takes an in-depth look at how the two groups fared in a third new colony, Hawai'i. Using plantation documents, missionary records, government documents, and oral histories, Poblete analyzes how the workers interacted with Hawaiian government structures and businesses, how U.S. policies for colonial workers differed from those for citizens or foreigners, and how policies aided corporate and imperial interests.

A rare tandem study of two groups at work on foreign soil, Islanders in the Empire offers a new perspective on American imperialism and labor issues of the era.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Islanders in the Empire by JoAnna Poblete in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Asian American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Illinois PressYear

2014Print ISBN

9780252082610, 9780252038297eBook ISBN

97802520964711. Letters Home

THE FAILURE OF PUERTO RICAN RECRUITMENT

On August 7 and 8, 1899, the San Ciriaco hurricane swept through Puerto Rico with winds up to one hundred miles per hour. Twenty-eight days of torrential rain caused approximately thirty-four hundred fatalities, massive flooding, and at least $7 million dollars in agricultural damage. Tens of thousands of people lost their homes and means of livelihood. Not only was the 1899 coffee crop destroyed, but critical shade trees, coffee bushes, and topsoil were also blown away. It would take at least five years before coffee would be profitable again in Puerto Rico.

Before the hurricane, the industry was already declining due to a drop in bean prices. Many landowners started collecting the smallest of debts from their laborers, heightening the impact of agricultural production losses at all levels of society. As Pablo Vilella Pol explained, “The disaster has immersed all citizens in the most terrible misery without distinction between classes … since the landowner lacks the most elementary things to maintain his family, the proletarian and working classes are in an even sadder situation.”1 All groups in Puerto Rican society were facing major economic and social problems at the turn of the twentieth century. According to Kelvin Santiago-Valles, the Puerto Rican working class during this period faced a combination of starvation, inflation, unemployment, and land dispossession that resulted from early U.S. economic policies in the region.2 To cope with such harsh conditions, exacerbated by the hurricane, many from the poorer classes engaged in criminality and social violence such as arson, stealing cattle or food, and rioting against the elite.

While economic downturns, colonial meddling, and natural disasters were not new to Puerto Rico, this chain of events happened in a new context—the islands had just become a colony of the United States. Even though the political-legal status of these former Spanish colonial subjects was not officially determined until the 1904 Supreme Court ruling in Gonzales v. Williams, Puerto Ricans were able to circumvent U.S. immigration restrictions and travel to the Territory of Hawai‘i to work on sugar plantations after 1898.3 Such movement promised an improvement in living conditions that historically motivated mobile livelihoods, or the seeking of life enhancements through moving to a new area. Blase Camacho Souza believed her family came to Hawai‘i because “they were looking for a place that would give them a job. They came because of the … natural disasters, the hurricane that had wiped out a lot of the coffee fields.”4 Their ambiguous legal status as U.S. colonials also gave Puerto Ricans the ability to escape desperate economic conditions in their homeland and migrate to another area of U.S. jurisdiction.

Workers and their families left Puerto Rico with hopes that life in the Pacific Islands would be less bleak and provide more opportunities for stability and success. Ismael García-Colón discussed the concept of buscando ambiente, or looking for opportunities, “a phrase used by both the landless and the parcel holders, [which] expresses the desire to improve one’s living conditions by looking for a place that offers better economic and social opportunities.”5 This motivation to constantly seek better circumstances propelled Puerto Ricans to migrate to Hawai‘i. Puerto Ricans numbering 5,023, including the Souzas, took advantage of their new colonial status and left poor conditions in Puerto Rico from November 1900 to September 1901 to work on Hawai‘i sugar plantations.

The U.S. federal government and the HSPA also had high expectations for Puerto Rican colonial labor recruitment to Hawai‘i. Officials in departments that managed colonial matters, such as the Bureau of Insular Affairs (BIA) and the Division of Territories and Possessions in the Department of Interior, encouraged intra-colonial movement to Hawai‘i as a remedy for unemployment and poverty in the Puerto Rican colony, as well as a solution to the constant labor shortage in the Pacific. The booming Hawai‘i sugar industry, established in 1835, always needed workers. From 1856 to 1940, labor-intensive sugar production in the islands grew from 547 tons per year to its peak of 9,170,279 tons annually in 1936.6 The HSPA hoped the settlement of Puerto Rican workers would provide a permanent solution to the consistent labor scarcity in the islands. U.S. colonial status also made Puerto Ricans attractive recruits due to their assumed new loyalty and dependence on the United States.

Despite the abundance of job opportunities in Hawai‘i, open colonial mobility within United States jurisdiction, and substandard living conditions in the Caribbean, Puerto Ricans stopped migrating to Hawai‘i after less than one year of recruitment. This chapter examines the ground-level experiences of early Puerto Rican colonial migrants to Hawai‘i, including the recruitment process and daily circumstances, as well as reactions to these policies. In the end, the desires of federal officials for such migration directly conflicted with the wishes of Territory of Hawai‘i leaders and the Puerto Rican government and people. Such tensions demonstrate the discrepancies that can occur within a global colonial system. In the case of Puerto Rican migration to the Pacific, intra-colonial policies encouraged by the highest level of government administration were rejected by other levels of the U.S. empire.

The Puerto Rican Recruitment Process

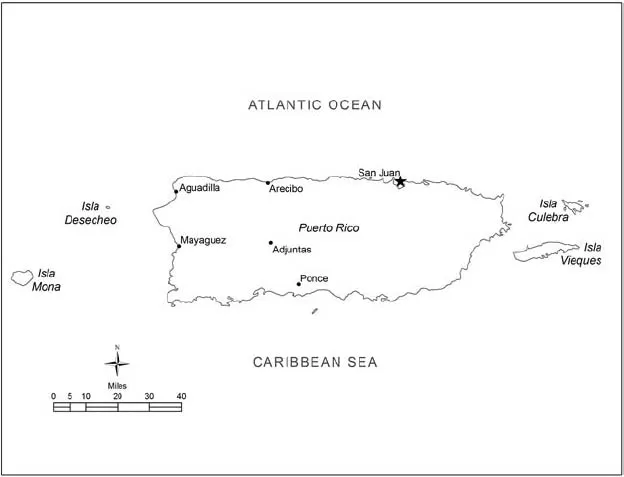

Two years after Puerto Rico became a territorial possession of the United States, the region’s inhabitants became the first U.S.colonial group recruited to Hawai‘i. The HSPA hired third party agencies in the Caribbean to enlist Puerto Ricans as permanent settlers, preferably families, to work on Hawai‘i sugar plantations starting in the summer of 1900. As independent companies, MacFie and Noble, as well as the New York and Porto Rico Steamship Company, advertised HSPA labor opportunities in local papers and obtained recruits from those who came to their offices in the port cities of Ponce, Mayagüez, Arecibo, Aguadilla, Adjuntas, and San Juan.

Recruiters received payment from the HSPA based on the number of people they recruited. These profit-oriented businessmen consequently shipped anyone they could convince to get on a boat. Little effort was made to examine Puerto Ricans during the boarding process. If you showed up at port on the day of a ship’s departure, you would likely be able to leave. Health inspections occurred upon arrival in New Orleans and Honolulu. The recruitment process was quick and haphazard.

The range of recruits included entire families, young single men and women, and some underage boys who left for Hawai‘i without their parents’ permission.7 The majority of workers came from the hurricane-ravaged southwest coffee growing region of Puerto Rico, a people described in one Spanish-language newspaper as “ruined by the lack of resources and poor credit…. [T]his month high winds of the storm have destroyed guavas, leveled guaragunos and destroyed large buds during the height of the flowering of the coffee crops.”8 Agriculture in this region was devastated, creating a large, desperate pool of potential laborers.

Map of Puerto Rico

In 1899, there was also an outbreak of thefts, cattle killing, and crop destruction by impoverished peasants throughout Puerto Rico.9 In Yauco, an angry mob visited a local coffee estate, killing the owner and cutting off the ear of the field boss.10 In 1900, more than two hundred out of eighteen thousand people in Adjuntas were reported to be dying every month due to starvation.11 No longer able to survive in the countryside, people from this area went to cities to find other ways to make a living. This population was the main target of recruiters for the HSPA.

Many U.S. colonials were willing to leave Puerto Rico because labor agents encouraged the belief that Puerto Ricans could lead a better life in Hawai‘i. Some migrants claimed that recruiters promised certain benefits that they never received. According to one recruit interviewed by the San Francisco Examiner,

[Señor MacFie] said … that before leaving San Juan I should be presented with $23, and that on the voyage from San Juan to New Orleans there should be for the Porto Ricans a physician known to us and good clothing for all who were in need of it. But at San Juan he at first refused to pay me any money, and when all of us made protest and many refused to make the voyage he paid each of us $5 and promised that more should be paid later, which has not been done. And the physician was not provided, nor the clothing, except that a few who were nearly naked were a very little helped.12

When promises of monetary compensation, material goods, and health services did not materialize, recruits tried to protest. Sometimes they succeeded in receiving better treatment. But once they embarked on the long journey to Hawai‘i, these intra-colonials had little recourse if their demands were not met. Aurelie de Soto explained, “When I began to learn my situation I wished to quit, but I was told that it was dangerous to rebel in the United States, because I might be hanged on a telegraph pole.”13 Rumors, uncertainties, and fears about their unknown futures were common on the trip to the Pacific.

Some recruits claimed they were told that Hawai‘i had similar conditions to Puerto Rico. One recruit, named Santiago, was told “that Hawaii would be like Porto Rico to me, because there the Spanish language was everywhere.”14 Conditions were actually quite different. Few people spoke Spanish, and Puerto Ricans were unaccustomed to the food available in the Pacific, as well as the higher costs of products. According to a Spanish-language article by Puerto Rican columnist Manuel Romero Haxthausen, “The food there is very different from our own and also very expensive.”15 As scholar Norma Carr explained, women had to bring samples of the food they wanted to buy to communicate their grocery needs to non-Spanish-speaking plantation store clerks.16 Unfulfilled migrant expectations created during the recruitment process led to negative views of both enlistment procedures and life in Hawai‘i among Puerto Rican U.S. colonials.

These views soon came to shape how the Puerto Rican migration process to Hawai‘i was reported in both English- and Spanish-language newspapers printed in the continental United States and Puerto Rico. One report in the San Francisco Chronicle claimed that “they were loaded on a boat in Porto Rico with the understanding that they were going to the opposite side of the islands to work, but after six days they were landed in New Orleans and rushed on to a train. They learned in San Antonio where they were being taken to, and have since been trying to escape.”17 This story of complete deception contrasts with another story about the happy ignorance of recruits printed just seven days later. An article in the San Francisco Call claimed that Puerto Ricans were “happy, well fed and ragged, joyously jingling small change … not a word of evidence that they were being mistreated.”18 Such a range of reports obscures the details of what labor agents actually told U.S. colonials to convince them to board boats in Puerto Rico. Recruiters may have given individuals false information, or they may have been misunderstood by migrants, who may have had unrealistic expectations. Recruitment terms were likely misrepresented or misinterpreted by people on both sides.

Throughout this process, the Puerto Rican government chose not to get involved. Charles H. Allen, the U.S.-appointed civil governor general, distanced himself from recruitment activities, simply stating in his first annual report in 1901 that “it is the privilege of every person to emigrate if he chooses so to do.”19 With regard to the future of Puerto Rico’s economy, Allen downplayed the effects of out-migrants, who he said totaled less than half of 1 percent of Puerto Rico’s population. He did not see Puerto Rican intra-colonial movement to Hawai‘i as significant or cause for concern.

With no local government involvement in this process, for-profit recruitment agencies hired by the HSPA were free to inundate the Puerto Rican public with unfettered advertisements and unchecked promises about a superior life in the Pacific. In light of the horrible economic conditions in Puerto Rico at the time, this strategy worked initially. However, once firsthand accounts about the poor conditions during the trip to Hawai‘i and the reality of work and living circumstances in these Pacific Islands were sent back to Puerto Rico, support for this type of intra-colonial movement quickly dwindled.

The Long Journey

The intra-colonial journey to Hawai‘i was long and arduous. The voyage lasted about twenty-one days. First, Puerto Ricans boarded boats in the Caribbean for the Port of New Orleans. From there they took cross-country trains to either Los Angeles or San Francisco, where they were transferred to ships bound for Hawai‘i. In Honolulu, many were placed on smaller, interisland boats to reach their final destination at an outlying Hawaiian island. Eleven groups of Puerto Ricans traveled to Hawai‘i between 1900 and 1901, the first on November 22, 1900. Though this initial group of 114 survived the trip, complaints about food during transport and a handful of deaths were common in subsequent shipments of migrants.20 With every group of approximately 522 recruits, there was an average of sixteen individuals who did not continue at some point durin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Defining U.S. Colonial Experiences: The Long History of U.S. Expansionism

- 1. Letters Home: The Failure of Puerto Rican Recruitment

- 2. Flexible and Accommodating: Successful Recruitment and Retention of Filipinos

- 3. Indefinite Dependence: U.S. Control over Puerto Rican Labor Complaints

- 4. Tensions of Colonial Cooperation: Philippine Authority over Labor Complaints

- 5. Conflicting Convictions: Filipino Ethnic Minister Interactions with the Plantation Community

- 6. Limited Leadership: Roles of Puerto Rican Labor Agents in the Plantation Community

- Conclusion: Current Struggles against U.S. Colonialism and Empire

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index