![]()

V

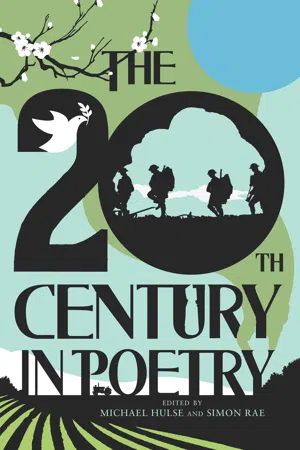

1946—1968

Peace and Cold War

AFTER THE greatest conflict in the world’s history, an estimated sixty million people had lost their lives, more than half of them civilians. Cities had been reduced to rubble, factories flattened, infrastructures destroyed. If the First World War had enforced the conclusion that civilisation was ‘botched’, the Second World War taught the grimmer lesson that in reality there was no such thing as civilisation. In ‘The Shield of Achilles’ Auden denounced the brutality to which mankind has been enslaved from time immemorial, in terms informed by recent history. Thetis, the mother of Achilles, looks into her son’s shield in the hope of finding images of peace, order and prosperity, but instead finds totalitarian oppression at an individual level, the abject abdication of basic human values: kindness, tolerance, love. The Indian poet Nissim Ezekiel developed a similar theme of disillusion in ‘The Double Horror’ — for all the possibilities of good within the world, human complicity in the negative seems certain to condemn humanity to a bleak future. If Australian poet Judith Wright employed military imagery to establish the threat to her lovers in ‘The Company of Lovers’, the message was not least that the menace Auden had expressed immediately before the war, in ‘“Say this city has ten million souls”’, had not been mitigated by the blood-letting.

Elizabeth Bishop, who spent much of her life travelling, reminds us of the exhilaration implicit in cartography, but around the world maps were being re-drawn to reflect new realities of power. While half the countries of Europe fell under Stalin’s empire of satellite states, behind what Churchill dubbed the ‘Iron Curtain’, across the globe Britain’s tired imperial pretensions were succumbing to the unstoppable pressure for independence. India was the first to go, released by the Labour government which replaced Churchill’s war coalition in the election landslide of 1945. However, the divide between the Hindu majority and the Muslim minority meant that the sub-continent had to be divided, creating the new nation of Pakistan. Partition, as it was known, appeared to be a political necessity, but its human cost was high. Although a ruinous civil war was avoided, the bloodshed that followed British withdrawal was appalling, with thousands losing their lives in sectarian massacres.

By the end of the Forties, poets (like everyone else) were beginning to sense the uneasiness of the new peace and project imaginary versions of the war which really would end all war. Kingsley Amis recasts

murderous geo-political rivalries as an Agatha Christie-style country house murder story, while Edwin Muir’s ‘The Horses’ is a bleakly moving post-nuclear holocaust pastoral. The conflict with which the new decade opened did not lead to apocalypse, but as the first ‘hot’ war between the West and Communism, Korea was a sour foretaste of the possibilities of mutual destruction, especially when China offered military support to her Stalinist southern neighbour, North Korea. R. A. K. Mason’s sonnet of scathing reproof to veteran American General Douglas MacArthur sounds a note of moral fury that would be heard many times over through the Cold War.

To seek for a thread running through the poetry of the Fifties is to be confronted by many different and often incompatible narratives. That fact in itself is eloquent of the changed nature of life in the second half of the twentieth century, when the old certainties were felt to have lost their purchase and validity. For Gwendolyn Brooks, the American experience was expressed in a gently observant poem about the vast disparities in wealth — and life-expectancy — between the well-off whites and the slum-dwelling blacks. For Adrienne Rich, the same endless class divide is viewed through the other end of the telescope, recording an uncle ruminating on cultural benefits of wealth and the dangerous threat from the discontented have-nots. The Fifties saw the rise of the Beats in America, led by the novelists Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs and poet Allen Ginsberg, who shot to fame with outspoken and outlandish counter-culture poems which he read to enraptured young audiences. Poems like ‘America’ and ‘Howl’ scandalised the nation with their rejection of unquestioned certainties concerning patriotism, religion, sexual orientation and drug use. Like his Russian counterpart, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Ginsberg extended the poet’s remit, travelling the world as an unofficial ambassador for peace and goodwill. Ginsberg found a home for his poetry with City Lights, San Francisco, run by fellow poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who was a similarly radical sensibility, writing copiously about the manifest injustices that have plagued humanity down the ages. In the poem here, he holds up the terrifying realism of the great Spanish painter Goya as a mirror to contemporary America.

These were American identities not envisioned in the polished, poised poetry of Richard Wilbur, or the open-to-all parlando of Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘At the Fishhouses’, or indeed the newly candid but formally and socially astute poetry of Lowell, Snodgrass, Sexton and Berryman. Confession, a complex idea with a lineage from St Augustine through Rousseau to Salvador Dalí’s Secret Life, was identified by critics as the main impulse behind a new sensibility of self in American writing. W. D. Snodgrass wrote with arresting honesty about the aftermath of a messy divorce, focusing particular...