- 783 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

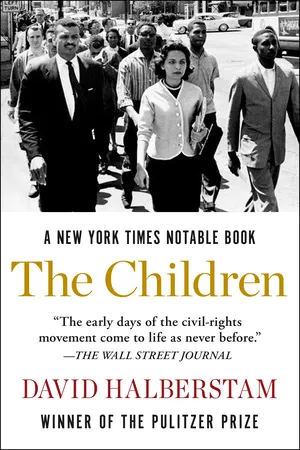

The Children

About this book

From the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of

The Fifties: An "intimate and monumental" account of the people at the core of the civil rights movement (

Publishers Weekly).

The young men and women at the heart of David Halberstam's brilliant and poignant The Children came together through Reverend James Lawson's workshops on nonviolence. Idealistic and determined, they showed unwavering bravery during the sit-ins at the Nashville lunch counters and on the Freedom Rides across the South—all chronicled here with Halberstam's characteristic clarity and insight. The Children exhibits the incredible strength of generations of black Americans, who sacrificed greatly to improve the world for their children. Following Diane Nash, John Lewis, Gloria Johnson, Bernard Lafayette, Marion Barry, Curtis Murphy, James Bevel, and Rodney Powell, among others, The Children is rooted in Halberstam's coverage of the civil rights movement for Nashville's Tennessean.

A New York Times Notable Book, this volume garnered extraordinary acclaim for David Halberstam, the #1 New York Times–bestselling author of The Best and the Brightest. Upon its publication, the Philadelphia Inquirer called it "utterly absorbing . . . The civil rights movement already has produced superb works of history, books such as David J. Garrow's Bearing the Cross and Taylor Branch's recently published Pillar of Fire. . . . Halberstam adds another with The Children."

This ebook features an extended biography of David Halberstam.

The young men and women at the heart of David Halberstam's brilliant and poignant The Children came together through Reverend James Lawson's workshops on nonviolence. Idealistic and determined, they showed unwavering bravery during the sit-ins at the Nashville lunch counters and on the Freedom Rides across the South—all chronicled here with Halberstam's characteristic clarity and insight. The Children exhibits the incredible strength of generations of black Americans, who sacrificed greatly to improve the world for their children. Following Diane Nash, John Lewis, Gloria Johnson, Bernard Lafayette, Marion Barry, Curtis Murphy, James Bevel, and Rodney Powell, among others, The Children is rooted in Halberstam's coverage of the civil rights movement for Nashville's Tennessean.

A New York Times Notable Book, this volume garnered extraordinary acclaim for David Halberstam, the #1 New York Times–bestselling author of The Best and the Brightest. Upon its publication, the Philadelphia Inquirer called it "utterly absorbing . . . The civil rights movement already has produced superb works of history, books such as David J. Garrow's Bearing the Cross and Taylor Branch's recently published Pillar of Fire. . . . Halberstam adds another with The Children."

This ebook features an extended biography of David Halberstam.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

BOOK 1

THE CHILDREN

Prologue

YEARS LATER THOUGH SHE could recall almost every physical detail of what it had been like to sit there in that course on English literature, Diane Nash could remember nothing of what Professor Robert Hayden had said. What she remembered instead was her fear. A large clock on the wall had clicked slowly and loudly; each minute which was subtracted put her nearer to harm’s way. What she remembered about the class in the end was her inability to concentrate, and the fact that both her hands were soaked with sweat by the end of the class and left the clear handprint of her fear on the wooden desk. It was always the last class that she attended on the days that she and her colleagues assembled before they went downtown and challenged the age-old segregation laws at the lunch counters in Nashville’s downtown shopping center. No matter how much she steeled herself, no matter how much she believed in what they were doing, the anticipatory fear never left her.

It had been at its height the night before the first sit-in, on February 13, 1960. On that evening, she had sat alone in her room at Fisk University. Suddenly she was hit with an overpowering attack of nerves. What had she gotten herself into? she wondered. She was supposed to march that next day into downtown Nashville and challenge the existing white power structure. She, Diane Nash, a coward of the first order in her own mind, a person absolutely afraid not just of violence but of going to jail, was going to join a small group of black children and ministers and take on the most important and resourceful people in a big, very white, very Southern city. She and her friends, who had nothing and were nothing, were going to go up against white businessmen, who were rich and powerful and connected to the white politicians, who were their pals and who agreed with them on everything. What had all of them been thinking in Jim Lawson’s workshops on nonviolence? These men would have nothing but scorn for a bunch of black children venturing into their territory.

These were white men in their forties and fifties and sixties. They owned the police force of the city and they owned the judges who sat in the city’s courts. And she, Diane Nash of Chicago, could not make a phone call to a single powerful person in all of America if her life depended on it, which indeed it might. She was now all of twenty-one and she was in way over her head. Somehow she had been caught in the camaraderie, and had begun to surface as someone outspoken and confident. The others, she knew, had already started to look up to her as a leader, but they had no idea how scared she was. It was a joke, she thought, it will never happen. We are a bunch of children. We’re nice children, bright and idealistic, but we are children and we are weak. We have no police force, no judges, no cops, no money. Jim Lawson is a fine man and a good leader, she thought, but this is nothing but a dream. She could almost see those powerful white men, like the white men she had seen in movies, who sat around and knew how to make decisions, hearing the news that a small group of black students were insisting on being served at the lunch counters at downtown stores, and laughing at them. She felt pure terror in her heart at that moment, and if there had been any way she could disappear from the movement without causing great shame to herself and letting down these others, she would have done it. If there was anything besides the cause itself which kept her from bailing out, it was the growing loyalty she now felt to the others in this small and, she hoped, hardy group of young students who had become not merely her colleagues, but now, her friends. They had started out quite tentative with one another; they came from different parts of the country, went to different schools, and there were obviously significant differences in class among some of them. What they shared, however, was a powerful common purpose, one which was becoming a more dominant part of their lives every day: The more committed they were, the more their past differences seemed less important, and their new political kinship became the critical part of their daily lives. It was as if the longer they stayed in, the more they left their old world with their old friendships behind, and the more this new political incarnation became the single dominating part of lives which had suddenly been completely redrawn. Besides, she liked them: Rodney Powell was a medical student, serious and cerebral and well spoken. John Lewis was rural and shy, but he was already known by the others for the steadfast quality of his character—there wasn’t anything he would not do for the cause. Curtis Murphy was full of laughter and charm. Gloria Johnson was obviously bright, but shy and a little stiff. Jim Bevel was provocative, a little older than the others, difficult, brilliant, but unpredictable, a young man whom the others both admired but found prickly. The more she knew them, the more she was impressed by them. Now, above all, she did not want them to think badly about her.

Besides, she shared their passion for the cause. She knew exactly why, despite her fear, she had joined up with them. Soon after arriving at Fisk the previous fall she had been taken to the Tennessee State Fair by one of the many young men vying for her attention. Since there did not seem a lot to do in Nashville socially, at least not compared with Chicago, or Washington, where for a time she had been a student, she gladly went along. There for the first time in her life she encountered signs for segregated rest rooms. WHITE ONLY, the sign had said, the first of those most odious signs she had ever beheld. And then COLORED. The humiliation she had felt was immediate—it was as if someone had slapped her face. What shocked her even more was that her date, who was from the South, did not seem surprised or offended; he quite willingly seemed to accept it. But for her the experience was so transcending, her anger so immediate and so complete that she was effectively politicized from that moment on. It was her first encounter with overt legal discrimination—she had known covert discrimination in Chicago, but she had always managed to look away. Worse, that terrible day at the fair had been followed up very quickly by other comparable humiliations. As a girl growing up in Chicago she had been accustomed to going downtown and shopping with her friends. There had been a certain aimlessness to those shopping trips. They would wander through the great department stores of the city, enjoying the role of shopper and viewer, and then they would have lunch at a restaurant in one of the stores. But when she tried to do this in Nashville she found that the store owners welcomed her money on most floors of the store but that she and her friends were not welcome in their lunchrooms. That had angered her every bit as much as the moment of humiliation at the state fair. After that she had begun to take notice of what was around her in downtown Nashville: In the center of the downtown there were black people eating their lunches while sitting on the sidewalk. That was yet another shock to her. She had come to the South almost casually, choosing Fisk because she was restless with her life at home. She had not thought very hard about the racial consequences of what she was doing—a black woman raised in the North moving to a region where the laws of segregation were just coming under legal and social challenge.

That was why when a fellow student had quite casually mentioned that a black minister was holding workshops designed to challenge the local segregation laws in downtown lunch counters, she had been an eager recruit. It was, she had thought at first, out of character to do this. It soon became obvious, however, that she was one of the most forceful members of this small band of students. By mid-February 1960 the others—the men—had come to her and asked her to be one of the two leaders of the group. The men were impressed by her in no small part because she was so brave and she exuded confidence. There she was, the others thought, the slightest of them, a girl at that, and she was fearless. Nothing stopped her. When they had been pummeled, she never considered turning back. Not for an instant. If anything, the harsher the attacks on them, the more determined she had seemed at their next meeting to go right back to the exact same place and show that they could not be intimidated by hate and violence. That violence would not deter them. The men in the group felt if she could stand up to the fear, then they could keep going back too. The truth was that she was always scared. Always. Her memories of sitting in Professor Hayden’s class were among the clearest of her undergraduate days. She remembered watching the clock, and she remembered in great detail the mark her soaked palms left on the desk. She had had to will herself to leave the class, to become once again the fearless leader that they had turned her into and that they believed she was. If the others thought she was Diane the fearless, she knew better; she knew she was Diane the coward. As the clock had ticked in Professor Hayden’s class she became more aware of the rising quality of anxiety she felt, and as she had left that class to venture forth once again as a leader of the movement, she could look down on her desk and see the wet handprint of fearless Diane Nash of Chicago.

It was not a lark for her. She had joined for serious reasons, and it—the commitment to a radical, nonviolent way to change America—became in different ways with different manifestations a lifetime devotion. From the start she had found a spiritual home in the Lawson group. If there was one source of strength she and the other young people in this embryonic movement had, it was, more than anything else, a belief in each other. A few, particularly those who attended the little black Baptist seminary nearby, had a special, immutable faith in their God to sustain them. Others did not. But all had gradually come to have faith in each other, even though in most cases their friendships were still quite tenuous. Some of the friendships born of those days would last a lifetime, and more than one marriage would come from this small group.

Most of them came from different towns and cities and states in the South. A handful of them were from the North. Most of them were black but a few were white exchange students attending black colleges. Because there were four black schools in the Nashville area, the students’ links were to each other rather than to their schools, and years later they would not identify themselves as graduates of Fisk or A&I, or Meharry or American Baptist, but first and foremost as sit-in kids. Scorned and mocked and teased by many of their classmates in those early days for being do-gooders as they undertook this challenge, they formed what was in effect their own university.

They did not think of themselves in those days as being gifted or talented or marked for success, or for that matter particularly heroic, and yet from that little group would come a senior U.S. congressman; the mayor of a major city; the first black woman psychiatrist to be tenured at Harvard medical school; one of the most distinguished public health doctors in America; and a young man who would eventually come back to be the head of the very college in Nashville he now attended. Another of their group would become one of Martin Luther King’s principal and most favored assistants, a young man who was so hypnotic a speaker that King often used him at major rallies as his warm-up speaker. Others would go on to lives which were relatively more mundane, and their days in this cause would remain the most exciting and stirring of their lives. A few became, if not casualties of those days, then men and women whose most exciting and most valuable moments had come when they were very young and whose lives never quite measured up to what some had believed was their early promise; they were not unlike brilliant combat leaders in America’s wars who never handled in peacetime an existence which was routine as well as they had handled one fraught with danger.

The journey they were beginning had started with a limited enough objective: an assault on the segregated lunch counters in Nashville, a seemingly pleasant city in a border state. But there was an inevitable progression to their cause, and gradually it became something of a children’s crusade as they and hundreds and thousands of black students like them throughout the country, knowing that the right moment had finally arrived, became part of a growing challenge to segregation in the South. As that assault grew it created among these young people its own new equation: They could not begin and end this quest with nothing grander than the right to eat lunch counter hamburgers. Each victory they gained demanded a further step; the totality of segregation as it existed in the American South in February 1960, when they began, meant that most of them would not be able to turn back, not at least for several years, and they would be caught in an escalating spiral in which they kept pursuing ever more dangerous challenges to the forces of segregation in ever more dangerous venues—in small towns and cities in the Deep South. They had begun by believing that by coming aboard and joining the sit-in struggle, they would be risking their bodies in some marginal and not very terrifying way in this semiprotected environment; within two years some of them would be risking their lives every day as the shock troops in the final challenge upon legal and political segregation in Alabama and Mississippi.

No one reflected that remarkable transformation from scared young black student to black student samurai more obviously than this shy, often timid young woman, Diane Nash. In Nashville in the beginning days of February 1960 she was frightened each day, scared that her fear would give her away to their enemies, to her friends, and to herself. Yet somehow she was able to overcome it and impress her peers. And this was just the beginning of what was to become her dramatic interior conversion: In a little more than two years, in the spring of 1962, she would have so overcome her normal psychic barriers of fear that she would stand in a Jackson, Mississippi, courtroom. There, already six months pregnant, surrounded by sworn enemies, accused on a trumped-up charge of contributing to the delinquency of a minor, because she and her friends had tried to integrate local facilities using high school students, she would stand her ground. In that Jackson courtroom she would boldly tell the white judge (a man duly stunned to find that the young integrationist he intended to slap into jail was in fact very pregnant) that it did not matter whether she went to jail or not, because her child was going to be born in Mississippi and any black child born in Mississippi was already born in prison. It would be the judge, who, sensing the fire in her and wanting no part of the potential public relations disaster of sending this pregnant woman to jail, would back down and suspend her sentence.

Almost from the start her peers had sensed her special capacity to rise to the occasion, and they made her their chairman. It was an honor she desperately wanted to decline. The fact that her friends believed in her and wanted her as a leader had, however, made her fear, if anything, greater than ever, because her recognition was greater: Since she was a leader of the Nashville sit-ins, she became more a marked person than ever before. There were more photographs of her in the local papers, and the television cameramen seemed to look for her when they covered the story, inevitably drawn to her because she was the most glamorous person in the group, slim and striking. Defiance of the white authorities was written all over her face. The fear was concealed within.

Yet every time she and the others left the First Baptist Church, where the workshops had been held and which they also used as a staging area before heading for the lunch counters, and walked the handful of blocks to the heart of the downtown shopping area, Diane Nash could feel the white violence begin to surge around them, the white toughs heckling them and throwing things and screaming cruel racial epithets. Then as they entered the restaurants and tried to take their seats, there would almost always be the violence, the hoodlums pouring coffee on the protesters and trying to extinguish cigarettes on their heads. There were, she was aware, no immunities for her. On February 20, at the time of the second major sit-in, she was in the downtown area, working as a control person—this was before the days of portable phones, and so the control people were important; they were like the communications men in war, the eyes and ears of the headquarters.

The downtown had been crowded on this day, and unusually dangerous too. There were groups of young white marauders looking for blacks on the streets. There had been a picture of Diane in The Nashville Tennessean a few days earlier, and one of the roving white marauders had shouted, “There she is! That’s Diane Nash! She’s the one to get! She’s the one to get!” She had quickly slipped away through the crowd, but she was terrified. They knew her face now and they were after her. She was a marked person.

She found a spot where she could get away from everyone and she sat down on the corner. The whites had looked tough, and there were reports that some of them were now carrying knives. She sat on a curbstone and took a fifteen-minute break. She found that she was gasping for air, though she had not run. It was as if the fear had sucked all the oxygen out of her system. She had to decide whether she had the strength to continue her job. Her dilemma was clear: If she could not conquer her own fear, how could she send the others out? And if she could not conquer her fear, would she have to resign not just from the leadership position but from all aspects of the sit-ins? The most important thing she had learned from reading Gandhi during the workshops she had been attending for almost three months was that leaders did not expect others to do things they were not willing to do themselves. That was true for cleaning latrines, and it was true as well for risking their lives.

She knew she had to make a decision and make it quickly. If she failed here, she would have to leave the Movement. She sat for a time, and gradually her ability to breathe came back. She thought about how important the sit-ins had become to her; she realized that this was the most important thing she had ever done, and perhaps more valuable than anything she might ever do again. Overnight, because of the sit-ins, she had felt of value to herself. Therefore she had to go forward—she owed it not just to the others but, in a way she had never felt before, to herself. She would be extremely careful in every decision she made—there would be no recklessness. But she would not turn back. If something terrible was going to happen to her, she decided, let it happen when she was doing something she believed in. She got up and walked back to her job.

1

THE EVENTS WHICH WERE just about to take place first in Nashville and then throughout the Deep South had been set in motion some three years earlier in February 1957, when two talented young black ministers, both of them strongly affected by the teachings of Mohandas Gandhi, had met in Oberlin, Ohio. One of them, Martin Luther King, Jr., was already world famous, having led the successful Montgomery bus boycott which had begun in December 1955, thereby emerging as the best-known leader of a new generation of black ministers; a year earlier he had been named the head of a new organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a group of young activist black ministers who intended to use the techniques of Christian nonviolence to challenge segregation throughout the South. The other minister, Jim Lawson, was unknown not only to the country at large but to the other leaders of what was already becoming known as the Movement. Jim Lawson had entered Oberlin College a few months earlier in order to get his master’s degree in religious studies. His more traditional academic and ministerial career had been interrupted for the past four years, first by nearly a year spent in a federal prison as a conscientious objector, a young black ministerial student who had rejected his government’s rationale for the Korean War and had refused to register for the draft; and then, after he had been released from the federal penitentiary, by three years studying and teaching as a Methodist missionary in India.

India had been a rich experience for Jim Lawson and had strengthened his belief in nonviolence as an instrument for social change, to be used eventually in the emerging civil rights struggle in the United States. Jim Lawson, son of a distinguished minister, was determined to be not just a minister but an activist minister, a man who used the church not merely to comfort the members of his congregation but to spread a social and political gospel as well.

In his last two years overseas Jim Lawson had felt a growing pull to return to the United States, a pull which began the moment he read in the Indian papers of developments in Mo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- BOOK 1: The Children

- BOOK 2: The Valley of the Shadow of Death

- BOOK 3: Coming Home

- Image Gallery

- Author's Note

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

- Notes

- Index

- A Biography of David Halberstam

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Children by David Halberstam in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Historia de Norteamérica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.