- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

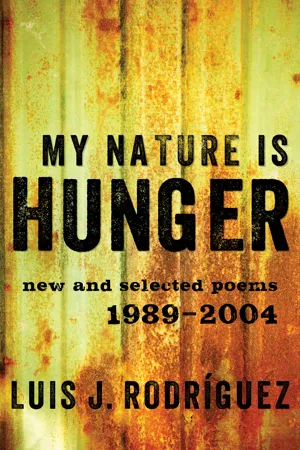

The collected poems of one of America's foremost balladeers of urban struggle and immigrant dreams

Over his three-decade career as a poet, novelist, and memoirist, Luis J. Rodríguez has earned acclaim for his remarkable ear for the voices of the city. My Nature Is Hunger represents the best of his lyrical work during his most prolific period as a poet, a time when he carefully documented the rarely heard voices of immigrants and the poor living on society's margins. For Rodríguez's subjects, the city is all-consuming, devouring lives, hopes, and the dreams of its citizens even as it flourishes with possibility. "Out of my severed body / the world has bloomed," and out of Rodríguez's stirring vision, so has beauty.

This ebook features an illustrated biography of Luis J. Rodríguez including rare images from the author's personal collection.

Over his three-decade career as a poet, novelist, and memoirist, Luis J. Rodríguez has earned acclaim for his remarkable ear for the voices of the city. My Nature Is Hunger represents the best of his lyrical work during his most prolific period as a poet, a time when he carefully documented the rarely heard voices of immigrants and the poor living on society's margins. For Rodríguez's subjects, the city is all-consuming, devouring lives, hopes, and the dreams of its citizens even as it flourishes with possibility. "Out of my severed body / the world has bloomed," and out of Rodríguez's stirring vision, so has beauty.

This ebook features an illustrated biography of Luis J. Rodríguez including rare images from the author's personal collection.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access My Nature Is Hunger by Luis J. Rodríguez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Poetry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

from Trochemoche – 1998

Meeting the Animal in Washington Square Park

The acrobats were out in Washington Square Park,

flaying arms and colors—the jokers and break

dancers, the singers and mimes. I pulled out

of a reading at New York City College

and watched a crowd gather around a young man

jumping over 10 garbage cans from a skateboard.

Then out of the side of my eye I saw someone

who didn’t seem to belong here, like I didn’t

belong. He was a big man, six feet and more,

with tattoos on his arms, back, stomach and neck.

On his abdomen were the words in huge old English

lettering: Hazard. I knew this guy, I knew that place.

I looked closer. It had to be him. And it was—Animal!

From East L.A. World heavyweight contender.

The only Chicano from L.A. ever ranked

in the top ten of the division. The one who

went toe-to-toe with Leon Spinks and even

made Muhammad Ali look the other way.

Animal! I yelled. “Who the fuck are you?” he asked,

a quart of beer in his grasp, eyes squinting.

My name’s Louie—from East L.A. He brightened. “East L.A.!

Here in Washington Square Park? Man, we everywhere!”

Then the proverbial “what part of East L.A.?” came next.

But I gave him a shock. From La Geraghty, I said.

That’s the mortal enemy of the Big Hazard

gang. “I should kill you,” Animal replied.

Hey, if we were in L.A., I suppose you would

—but we in New York City, man.

“I should kill you anyway.”

Instead he thrust out his hand with the beer and offered

me a drink. We talked—about what had happened since he stopped

boxing. About the time I saw him at the Cleland House

arena looking over some up-and-coming fighters.

How he had been to prison and later ended up homeless

in New York City, with a couple of kids somewhere.

And there he was, with a mortal enemy from East L.A.,

talking away. I told him how I was now a poet,

doing a reading at City College, and he didn’t wince

or looked surprised. Seemed natural. Sure. A poet

from East L.A. That’s the way it should be. Poet

and boxer. Drinking beer. Among the homeless,

the tourists and acrobats. Mortal enemies.

When I told him I had to leave, he said “go then,”

but soon shook my hand, East LA. style, and walked off.

“Maybe, someday, you’ll do a poem about me, eh?”

Sure, Animal, that sounds great.

Someday, I’ll do a poem about you.

Victory, Victoria, My Beautiful Whisper

For Andrea Victoria

You are the daughter who is sleep’s beauty.

You are the woman who birthed my face.

You are a cloud creeping across the shadows,

drenching sorrows into heart-sea’s terrain.

Victory, Victoria, my beautiful whisper,

how as a baby you laughed into my neck

when I cried at your leaving

after your mother and I broke up;

how at age three you woke me up from stupid

so I would stop peeing into your toy box

in a stupor of resentment and beer;

and how later, at age five, when I moved in

with another woman who had a daughter about your age,

you asked: “How come she gets to live with Daddy?”

Muñeca, these words cannot traverse the stone

path of our distance; they cannot take back the thorns

of falling roses that greet your awakenings.

These words are from places too wild for hearts to gallop,

too cruel for illusions, too dead for your eternal

gathering of flowers. But here they are, weary offerings

from your appointed father, your anointed man-guide;

make of them your heart’s bed.

Catacombs

The concave view over desert groves

is maligned, dense with sacrifices

not to be believed.

A native face peers backward to time

and woman, gathering memory like

flowers on healing cactus.

Your eye is froth & formation, it is

rain of protocol you can’t relinquish

as water is wasted on sacred sand.

Across the turquoise rug, hexagon shapes.

I discover you, the howl of eternal mornings

while beckoning the blue from this sky,

while gesturing an infant from sleeping tree.

Sip the maguey juice from these mountains,

shear chaos from the catacombs:

forget and ferment the pain.

On the back of your hand, circles of flame.

to the police officer who refused to sit in the same room as my son because he’s a “gang banger”

For Ramiro

How dare you!

How dare you pull this mantle from your soiled

sleeve and think it worthy enough to cover my boy.

How dare you judge when you also wallow in this mud.

Society has turned over its power to you,

relinquishing its rule, turned it over

to the man in the mask, whose face never changes,

always distorts, who does not live where I live,

but commands the corners, who does not have to await

the nightmares, the street chants, the bullets,

the early-morning calls, but looks over at us

and demeans, calls us animals, not worthy

of his presence, and I have to say: How dare you!

My son deserves to live as all young people.

He deserves a future and a job. He deserves

contemplation. I can’t turn away as you.

Yet you govern us? Hear my son’s talk.

Hear his plea within his pronouncement,

his cry between the breach of his hard words.

My son speaks in two voices, one of a boy,

the other of a man. One is breaking through,

the other just hangs. Listen, you who can turn away,

who can make such a choice—you who have sons

of your own, but do not hear them!

My son has a face too dark, features too foreign,

a tongue too tangled, yet he reveals, he truths,

he sings your demented rage, but he sings.

You have nothing to rage because it is outside of you.

He is inside of me. His horror is mine. I see what

he sees. And if my son dreams, if he plays, if he smirks

in the mist of moon-glow, there I will be, smiling

through the blackened, cluttered and snarling pathway

toward your wilted heart.

A Tale of Los Lobos

One summer, to watch Los Lobos play,

I drove several hundred miles

from Chicago to Charleston,

West Virginia with three

Chicano buddies: Geronimo,

Mitch and Dario.

We got there in time to catch

a great concert. Afterwards,

we went backstage and talked

to the band members.

We told the band we’d see them

later at the honky tonk club

where they were expected to perform.

But they had to leave right away

and couldn’t make it.

We arrived at the club, sans Lobos,

and the place was packed.

I didn’t think there’d be a seat,

but soon someone directed us to a table

where three pitchers of beer stood

at attention on the varnished table top.

Great service, I thought. We sat down,

poured beers into frosty glasses,

and took in the down-home blues

emanating from the small, smoke-filled stage.

Before we finished the pitchers,

three more were brought over

(although nobody had asked for our money).

So we drank away, enjoying ourselves,

the only Mexicans in the place.

What gives? I asked. Geronimo, Mitch and Dario

shrugged their shoulders.

Soon many eyes turned our way.

Something’s up, I whispered,

look at the way everybody’s looking at us.

Sure enough, the band stopped and someone

at the mike asked us to come up to the stage.

“¡Que cabula!” Mitch exclaimed, “they think

we’re Los Lobos!”

Damn, man, I said, we don’t even look like them!

Geronimo stood up, said he was sorry

but we weren’t Los Lobos, and sat down.

Everything stopped. Incredulous stares

surrounded us. After an embarrassing

silence, the house band began

a slow number, than upped the tempo,

finally rocking the place

with harmonica-laden fervor.

Hijo de su, they believe us, I said.

“I don’t know,” Dario replied,

“I think they think we’re lying.”

One dude approached us:

“I know you’re Los Lobos;

you just don’t want to play, right?”

No, for reals, we ain’t them, I responded.

He winked and kept on walking.

When I went to the restroom,

a woman by the phone stopped me:

“I liked the way you played guitar

at the gig earlier.”

That wasn’t me, I explained.

“What I want to know,” the girl then asked,

“is how you got rid of the goatee so fast.”

I took my piss and rushed back to my seat.

Rumors that we were Los Lobos abounded.

Some shouted for us to get off it and perform.

“If we did,” Geronimo quipped, “Los Lobos

would never play this town again.”

I then noticed a bevy of West Virginia beauties,

local groupies, who followed the out-of-town

bands that landed here. They wouldn’t leave

even after we gave them expressions that said:

you’re nice, but we ain’t them!

One girl who sat directly behind me

had on a prom dress! She kept

ordering gin-and-tonics, waiting for a signal

from one of us, I presumed, for her

to join us at the table. We decided not to go

this route. Mitch figured we might have to scram

if people here concluded we had

insulted their fair city, club and women.

All our denials seemed pointless,

resulting in more knowing winks

as if they were all in on our little joke.

The pitchers kept coming,

the house band coaxed us up

once or twice,

and the groupies held on

like real troupers.

Finally, people began to depart.

The band packed up its instruments

and most of the girls had split.

Then just before our last beer,

a loud thump exploded behind me.

I turned. The girl in the party dress

had fallen over in her chair,

drunker than shit! We helped her back

on the stool. My partners and I

promptly left the club

as quietly as we could

on the night Los Lobos didn’t play

in Charleston, West Virginia.

Woman on the First Street Bridge

Traffic crawled for miles in front of me

and a similar number of miles behind.

Sandwiched between a truck-bed piled

with oil-soaked auto parts and a crumpled sedan,

I felt like melting beneath the peppered sun

as I inhaled the fetid fumes, scratched

my steaming eyeballs and crept toward

the concrete bridge facing the jagged s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Publisher’s Note

- from Poems Across the Pavement - 1989

- from The Concrete River - 1991

- from Trochemoche - 1998

- New Poems

- Acknowledgments

- A Biography of Luis J. Rodríguez

- Copyright