![]()

Chapter One

Standing in the kitchen munching on pickled cucumbers, watching a stray dog pee in his yard, Jiro hears something crash into the garage door. The entire house trembles as if it is about to fall off its foundation.

He runs down the hall and yanks open the door. The electric garage door is broken, boards desperately clinging to the frame. Fragments of glass shimmer on the cement carport. The black Honda’s engine is still sputtering, spilling gassy blue smoke from the exhaust pipe. And there is his wife, sitting rigidly in the driver’s seat at a forward tilt, staring straight ahead as if she’s pondering whether to plow into the wall.

He rushes over to the car window and pounds on it. “Are you all right? What happened? Can you move? Open the window!”

Aiko doesn’t turn her head. Her white-knuckled hands grip the wheel. He looks at her fingernails, which he’s seen hundreds of times, but still he’s startled that they are so severely bitten, exposing raw pink skin. There is a moment of eerie silence, as if one world has shattered and another has yet to rise up in its place. Jiro can’t think what to do. Pull her out of the car? Call an ambulance? Her doctor? Her self-inflicted paralysis leaches into him and turns him into stone.

Last night in bed she told him again that her heart was punctured and her life was slowly dripping out of her. “What do you want me to do?” he said, not bothering to hide his frustration. Hasn’t she been talking like this for a year now? “Tell me and I’ll do it. I’ll do it right now.” Even he could hear the anger and helplessness in his voice.

As if coming out of a fog, Jiro realizes the door is unlocked. He opens it, turns off the engine, pockets the keys. She doesn’t appear to be physically harmed; and that’s the problem, he thinks. The harm is tucked deep inside. She’s seen dozens of doctors who’ve given so many different diagnoses, yet her hurt remains nameless.

Hanne sets down Kobayashi’s novel. The book did well in Japan, in part because Kobayashi revealed in an interview that his main character, Jiro, was inspired by the famous Noh actor, Moto Okuro. So intrigued, so fascinated was he by this remarkable man that Kobayashi began the book right after he met Okuro. “Moto cured five years of writer’s block,” Kobayashi told the magazine. “If he reads my book—and what an honor if he did—I hope he sees it as an homage to him.”

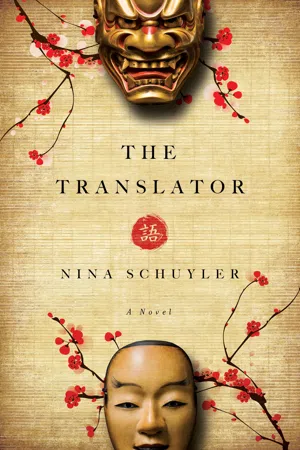

The name Moto Okuro meant nothing to Hanne, and she doesn’t know much about the ancient Japanese theater art of Noh, except that masks are used for different characters, and the characters speak in a stilted, almost unintelligible language. There’s music to contend with, and, almost like a Greek play, a chorus. She’d have to read Kobayashi’s Trojan Horse Trips herself first, on her own terms, she told the publisher. Only if she understood the main character would she be able to successfully translate the book into English. At her enormous blackboard, custom-made to take up one entire wall, she begins to write a sentence in Japanese.

Iradachi, the Japanese word for frustration. Of course you are frustrated, Jiro, thinks Hanne. You’ve brought your wife from one doctor to another, and more than a year later there is no sign of improvement, no answers. You are in the same place you were three, five months ago. And what has become of your life? Turned into something unrecognizable, you no longer know who you are.

She then writes Yariba no nai ikidoori, meaning an unfocused anger. But also yaru se nai kimochi, a helpless feeling, or a feeling of no way to clear one’s mind. A neat column of chalk characters fills the far side of the board.

She pauses, baffled. How can Jiro be experiencing an unfocused anger and a helpless feeling? And just a moment ago he was frustrated. It doesn’t make sense.

Whatever Kobayashi meant, she’s on her own here. Over the eleven months she’s been working on his novel, Kobayashi has responded to only a few of her e-mails and always with a curt—“Too busy.” “Figure it out.” “On another project.” Though, after the publisher sent him the first three translated chapters, he found ample time to quibble that she had cut his crucial repetitive words and phrases. But what does he know about translating Japanese, which prefers to keep someone guessing with its verb at the end of a sentence, into English, with its own linguistic quirks? Between the two languages, there are far too many nuances to name. After that charged exchange, based on Hanne’s counsel, the publisher decided to hold off sending him anything until the entire manuscript was done.

Unfocused anger Jiro may have, but not in the American way of yelling or stomping around the house, spewing vitriolics. Jiro means second son. Kobayashi would have done much better if he’d named him Isamu, which means courage. Jiro is a man of courage and enduring restraint who has been patient and loving and thoughtful and kind throughout this ordeal. Yes, ordeal. His wife begins to fade away for an inexplicable reason, and Jiro is left to salvage what he can of the marriage, of her. His anger would be quiet. Nearly invisible, but no less real.

Ittai nani o shite hoshii-n dai? What do you want me to do? Kobayashi dropped the verb, desu, which, if he used it, would have suggested a polite tone. Jiro is frustrated, at wit’s end.

Last night, Hanne dreamed Jiro whispered this same question to her, though his tone was not one of frustration, but seduction. For months now, she’s been dreaming about Jiro, erotic dreams, dreams of kisses stolen behind doors, of bare feet rubbed beneath tables, of tangled bedsheets and limbs. She can even conjure up his smell, or what she thinks it would be. Underneath his deodorant a slightly earthy smell, which she likes. That she’s fallen a little bit in love with him is no surprise. She’s spent months and months with him and when she wakes can’t wait for their daily sessions.

Another fragment from last night’s dream floats up to the surface of her mind. Jiro’s voice wasn’t just a sound nestled near her ear. It was all around her, as if his voice had become warm water and she was immersed in it. She also remembers water sloshing. And a porcelain bathtub. Steam. A man—Jiro?—was washing her feet, gently soaping each toe. Or was it David? No, she distinctly remembers the man speaking Japanese. And it wasn’t Hiro; she’d recognize her deceased husband’s voice. Besides, the dreams of Hiro always involve her taking care of him. In the beginning, Jiro’s hands made her skin tingle, her body melt. But the longer he touched her, the more his touch began to feel oddly sacred, like an anointing or baptism.

Some part of her brain becomes aware of hunger. When did she last eat? Breakfast, she remembers. An apple. A carrot. A long time ago, the phone rang. Maybe David, calling to find out if she’d have supper with him and what usually follows afterwards. From far off, she hears the foghorn blare on the Golden Gate Bridge. A low bank of clouds probably stretches over the steel-blue water, making it dangerous for ships to cross under the bridge. Looking out her office window, she’s surprised to see it is now dark, meaning she’s worked all day without a break. At some point she’ll have to make herself stop. Make herself eat. Try to sleep. But not now, not yet. She loves this. She can’t possibly interrupt this profound pleasure.

She pops a hard candy into her mouth.

Jiro rushes into the house and calls an ambulance. Then her doctor. As he listens to the phone ring, he rubs his face, wishing it were a mask he could scrub off. He is so tired. Her life has become unyielding, relentless darkness, as has his.

“I’ve done everything I can for her,” Jiro hears himself say to the doctor. His tone has a danko to shita kucho de that is new to his ear.

Danko to shita kucho de—in a firm tone of voice. You’ve tried everything, Jiro, Hanne thinks to herself. You’ve played out every hypothetical—what if Aiko wakes up smiling? What if she laughs today or the new treatment works? What if she’s magically, spontaneously her old self again? It is not just a firm tone, it is decisive. You’ve come to a decision, one that will fundamentally alter your life.

She translates: His tone has a decisiveness to it that is new to his ear.

Jiro says he fears for Aiko’s safety. He can’t quit his job and give her around-the-clock care. Unfortunately, he is not a rich man. “What I’m doing is no longer enough.” Hanne hears what he’s not saying: I am spent, everything sapped and now I’m a husk of myself. There isn’t any more; but if something more isn’t done, Aiko might not make it.

The doctor says he understands. These situations are very difficult, very hard. Jiro listens, but he’s not asking for permission or even understanding. Hanne intuits that. There is nothing, real or imagined, on the horizon. Nozomi wa nai, he says, there’s no hope.

There’s no future with her, thinks Hanne. Aiko will not improve, not under your care. This part of your life, the constant tending to your wife, the incessant worry, the fear for her safety, is now over. Finally, you’ll have peace. You’re surprised to hear me say that? I know this terrain. Remember, Jiro, the Greeks thought hope was just as dangerous as all the other world’s evils, because it prolonged one’s torment.

She translates nozomi wai nai as: His hope is gone.

Shikata ga nai, says Jiro. It can’t be helped.

When the doctor says he will meet the ambulance at the hospital and check her into the psychiatric ward, Jiro thanks him and hangs up. He hears the siren in the distance and shoves his knuckles into his mouth. Angrily, he wipes away his tears with the back of his hand and hurries to the garage. As the ambulance pulls into the driveway, his wife is still sitting in the driver’s seat, her face empty, as if she’s no longer fully in this world.

In the morning, Hanne’s son calls. Tomas, her eldest, her loyal son who dutifully phones once a week to ask about her well-being. He’s an excellent cook who, whenever he’s in town, likes to make her extravagant meals—Baeckeoffe and coq au vin and white truffle risotto—delighting in watching her eat. A thirty-three-year-old lawyer, he lives in New York City with his wife and two beautiful daughters.

“How is everyone?” says Hanne.

“Everyone’s fine,” he says, “just fine.”

She hears a remoteness in his voice. Everything is not fine, but, for whatever reason, he’s not prepared to talk about it yet. It’s her job to fill in the empty space until he’s ready. She tells him about the novel she’s translating from an up-and-coming Japanese author who is about to make his grand entrance into the American publishing world. She is, of course, assuring his entrance is grand. Working day and night, she loves it in the odd way when something consumes you. As she talks, Hanne wonders if the trouble is Anne. Seven years of marriage, that’s usually when a couple hits rough waters, when she and Hiro began to drift. She asks about her granddaughters, Sasha and Irene.

Sasha, the seven-year-old, reminds Hanne of her daughter when she was that age, with her raven hair, her slanted Japanese eyes, her nostrils shaped like teardrops. It’s been six years since she’s seen or heard from her daughter, Brigitte. Where is she now? Married? A young mother? Living in a city? The country? A veterinarian? A businesswoman? It’s mind-boggling how little she knows about her daughter.

Hanne imagines Tomas’s serious face, his lips tightening into two thin wires, brooding over the best way to phrase what he wants to tell her. He was always a careful, orderly boy, all his toys in separate cardboard boxes, which he neatly labeled, “cars,” “trains,” and a Christmas file begun in January where he stored his desires. Now Tomas is considered a success. If Hiro could see his son now. Tomas, who, as she understands it, can argue his way out of anything. Their son is tall; his height is his main inheritance from Hanne’s German-Dutch side of the family; most everything else comes from his Japanese father.

“Anne ...