![]()

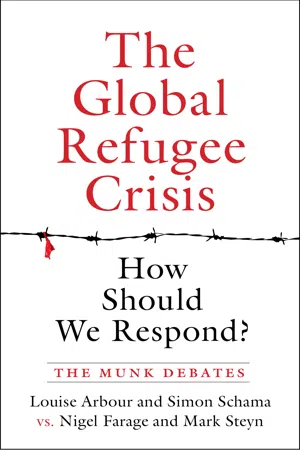

The Global Refugee Crisis:

How Should We Respond?

Pro: Louise Arbour and Simon Schama

Con: Nigel Farage and Mark Steyn

April 1, 2016

Toronto, Ontario

![]()

Rudyard Griffiths: Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the Munk Debate on the global refugee crisis. My name is Rudyard Griffiths and I have the privilege of organizing this semi-annual debate series and, once again, serving as your moderator.

I want to begin tonight’s proceedings by welcoming the North America–wide TV audience that is tuning in to this debate right now across Canada from coast to coast to coast on CPAC, Canada’s Public Affairs Channel, and across the continental United States on C-SPAN. It’s the first time the Munk Debate has been live throughout the continent of North America and it’s terrific to have that viewing audience joining us this evening.

A warm hello also to our online audience. They’re logging onto this debate right now on our website, www.munkdebates.com. It’s great to have you as virtual participants in tonight’s proceedings.

And finally, hello to you, the more than three thousand people who’ve once again filled Roy Thomson Hall on a Friday night to capacity for yet another Munk Debate. All of us associated with the Aurea Foundation thank you for supporting the simple idea that this debate series is dedicated to: more and better public debates. So, bravo, ladies and gentlemen. Thank you for being part of tonight’s conversation.

Our ability to continue these debates year after year, and to bring some of the world’s sharpest minds and brightest thinkers here to the stage, would not be possible without the generosity, the foresight, and the creativity of our hosts tonight. Please join me in a warm appreciation of the Aurea Foundation and its founders, Peter and Melanie Munk.

It’s the moment we’ve been waiting for. Let’s get our two teams of debaters out here centre stage and our debate underway. Our resolution tonight is taken from the inscription on the Statue of Liberty, “Be it resolved: Give us your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

Please welcome our first speaker in support of the resolution. She’s a former Canadian Supreme Court justice, chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunals for Yugoslavia and Rwanda, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCR), among many other accomplishments. Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome Canada’s Louise Arbour.

Louise’s teammate is the internationally acclaimed historian, cultural commentator, and art critic Simon Schama. Please come out on stage, Simon.

Well, one great team of debaters deserves another. Speaking against the resolution, “Be it resolved: Give us your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” is the renowned columnist, author, and conservative human rights activist Mark Steyn.

Mark’s debating partner is the leader of UKIP, the United Kingdom Independence Party, and a member of the European Parliament. He’s here tonight from the United Kingdom. Under his leadership, UKIP won almost four million votes in the 2015 national election. Ladies and gentlemen, Nigel Farage.

Before our debate begins, I need your help with a last-minute housekeeping item: our countdown clock, an invention we love at the Munk Debates. It keeps us on schedule and our debaters on their toes. When you see these clocks reach their final moments, join me in a round of applause that will let our debaters know that their time is up. We had Henry Kissinger up here once and he didn’t think his time was up … but I digress. I don’t think any of our debaters will make the same mistake.

Now, this is the part I enjoy most. We asked all of you here tonight to vote on the resolution on your way in. You were asked, “Do you support or oppose the motion, ‘Be it resolved: give us your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free’?” The results are interesting: 77 percent of you agree, and 23 percent disagree.

To give a sense of how much this debate is in play, we asked: “Depending on what you hear during the debate, are you open to changing your votes?” Let’s see that result. Wow: 79 percent of you were open to changing your votes. Only 21 percent of you are committed to your viewpoint. This debate is very much in play; either side can take it.

Let’s go to our opening statements. I’d like six minutes on the clock for each of our debaters. Ms. Arbour, your six minutes begins now.

Louise Arbour: Thank you very much. Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. The words of the motion that I’m here to support were written by a woman, Emma Lazarus, and these words are engraved on a famous statute of a woman holding a torch, and maybe less noticeably holding also the tablets of law with a broken chain at her feet. So it should come as no surprise to you that this has considerable appeal to me. But don’t let that fool you. This is not a sentimental call for do-gooders to unite, nor a romantic projection of what the new world is going to be all about.

Understood in today’s terms, it’s a moving, poetic way of capturing both the spirit and the letter of the 1951 Refugee Convention. It was written essentially because of and for Europe, and it remains the framework within which a world purporting to be governed by the rule of law must deal with the current refugee crisis in Europe and must also stop turning a blind eye to equally pressing crises elsewhere — in South Sudan, for instance. This is part of the “Never again!” that the world screamed loud and clear after the Holocaust and has betrayed on so many occasions since then. Today should not be one of those.

I want to look at this issue both from a Canadian and international perspective. The international framework is very clear. Virtually all of the countries concerned with the current flow of refugees fleeing the war-torn countries of Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia, and Libya are parties to the Refugee Convention, and they are obligated to grant asylum to those fleeing political and other forms of persecution. The protection framework that is set in place by the convention outlines that refugees should not be penalized for their illegal entry or stay in a country. The reverse would obviously be a way to completely emasculate the right of asylum, and the principle of non-refoulement precludes returning refugees to countries where they are at risk. This puts a disproportionate demand on countries that are more easily reachable than others. In the case of Syria, the neighbouring countries of Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey currently have some 4.5 million Syrian refugees, and the countries that are at the external borders of Europe — Greece, Italy, and so on — are also seeing a large influx.

This leads to another fundamental principle that underpins the Refugee Convention: the need for international co-operation and burden sharing, and I’m cautious here about using the word burden. Now I want to mention Canada. We often define ourselves by our geography, and on this issue our geography is relevant. The nature of our borders is such that we are virtually immune from a flow of asylum seekers arriving on our soil by land or sea — although, the result of the upcoming American elections may change that! We’ll cross that bridge when we get there. As a result, I believe we have a special obligation to provide for a generous resettlement program aiming both at welcoming refugees and at easing the burden on states that are struggling to live up to their international obligations. And I believe that with true international co-operation in place, this is eminently feasible. We should do it the smart way by ensuring that asylum seekers can travel safely to places of refuge, thereby undercutting the smugglers, and by deploying extraordinary resources to meet this extraordinary challenge.

I am aware of the fear that an influx of foreigners will transform our social fabric in an undesirable way, but the reality is that our social fabric is changing anyway in this increasingly interconnected world. We have a choice. We can look to the past and stagnate in isolation, or we can embrace a future in which our children will develop their own culture fully open to that of others, inspired by the choices that we are making today. The greatest threat to Western values is not an influx of people who may not share those values today; it’s the hypocrisy of those claiming to protect these values and then repudiating them by their actions.

I expect that we’re going to hear tonight that Muslims are different, that they pose a unique, novel, and existential threat to our democracies. Not only has this been the ugly response to just about every wave of new immigrants in history, but, ironically, it plays right into the hands of the violent jihadist groups that are attacking us. These violent groups have a political, not a religious agenda. They seek to destroy our democracies not by infiltrating or taking over our institutions but by letting us slowly self-implode in response to the fear that risks turning us against ourselves, thereby destroying the very key features of our open society. We need to be smarter than that, and we need to welcome people who, like all of us who came from somewhere else at some point, will build an ever-evolving free and strong Canada. Thank you very much.

Rudyard Griffiths: With time still on the clock. Mark Steyn, you’re up next. Your six minutes begins now.

Mark Steyn: Madame Arbour described a refugee situation that is not happening in Europe at the moment. The great question before us tonight is whether the “huddled masses” on those “teeming shores” are really “yearning to breathe free,” or whether they’re simply economic migrants who want to avail themselves of the comforts of advanced societies. There are three thousand people here in Roy Thomson Hall tonight. It would nice if everyone who lived in Toronto could be in Roy Thomson Hall right now, but if everyone in Toronto moves into Roy Thomson Hall, it isn’t Roy Thomson Hall anymore. And that’s the situation facing Europe today.

The people who have entered Europe are not refugees as the term has traditionally been understood and as Madame Arbour explained in terms of the Geneva Convention. In Europe in 2015, men represented 77 percent of the asylum applications — that’s an extraordinary population deformation. In most civil wars, this is the demographic that would be back home fighting for their country. It’s as if, during the American Revolution, General Washington and the rest of the chaps had gone off to France and left Martha and the other women and children back home to fend for themselves.

What does it mean to breathe free? Under the Taliban, it’s illegal for Madame Arbour to feel sunl...