![]()

Part One: The Rise

![]()

1

The Seven-Year Itch

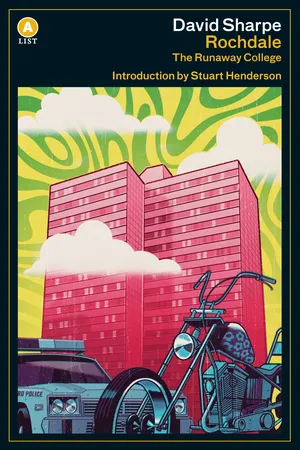

In the late Sixties, young idealists and rebels, 800 at a time, were given full control of an eighteen-story highrise in the heart of English Canada’s largest city. Rochdale College it was, this untested, bold idea on Bloor Street at the edge of the University of Toronto campus, a ten-minute walk from the Ontario Legislature. Rochdale College — a twin tower of raw concrete and straight lines in its second year of operation in 1970, the largest co-operative student residence in North America, the largest of the more than 300 free universities in North America, and soon to be known across the country as the largest drug supermarket in North America.

At that point in the decade, social gestures had become broad. Youth was a “movement”; the Americans were at war. The young idealists and rebels in the heart of Toronto had said they wanted to change — even revolutionize — education, but when the federal government gave them the money to do it, what they tried to challenge and change was society itself.

In August 1970, police staged a series of well-publicized raids against the College. Immediately, the public confirmed a suspicion that this was no ordinary building. Although there were many perfectly normal, responsible citizens within those walls, some of the young people there were holding a festival of dreams that the public didn’t share, couldn’t share, and they were holding those dreams in a fortress. Nothing short of an armed invasion — or a long war of attrition — would get them out. It was a set-up that surprised everyone, including the people who found themselves set up. It had never happened on that scale before, and — judging by the furor it caused — it will never happen again.

Rochdale College could have begun only in that experimental decade. In the Sixties, society had become, like a marriage, tired of itself, and Toronto, like a fretful spouse, searched for a lover. The city was feeling a Seven-Year Itch, a sort of menopause in which the pasture dries up and husbands seek new wives or runaway affairs. When Rochdale College arrived, it was as if Marilyn Monroe had moved in down the block.

By popular mythology, the Itch recurs every seven years. But with Toronto, it came only once — and lasted seven years. Indeed, for the seven years of its lifespan — from September 1968 to September 1975 — Rochdale became the itch that Toronto couldn’t scratch.

Through all the twists and turns of the story, the times took Rochdale seriously. The College received detailed press coverage, with frequent, impassioned letters to the editor. When Rochdale diplomas became available, payments came in the mail from all over North America, and some from Europe. Reports entered national magazines and national TV news, and as the word of mouth and media spread, young people loved what they heard. At least 5,000 lived in Rochdale at some point in their impressionable years. They came from, and went to, all parts of Canada. And in the States, Rochdale was an address contemplated by young men with draft-dodging or deserting on their minds.

The following pages document the way both the larger society and the Rochdalians themselves turned a community into a symbol and destroyed it. The Rochdale story has features which lift it from the local, Toronto scene into the continent-wide examination of the Sixties which has begun in the Eighties. Many in the group now holding positions in the social and business establishment were exposed to the ideological challenges of the Sixties and decided either for or against the social protest, the radical conservatism seen in health foods and communes, the killing of categories, the drugs. Rochdale played out a pure form of those challenges-in-action. The reader will find that, if he thought the Sixties were good, they were better inside Rochdale, and if he thought they were bad, inside they were worse.

Much of the following has been taken from internal publications, papers, and interviews — material not carried by the public press. However, looking behind the scenes carries some consequences. Surviving collections of internal publications, for example, are disorganized and partial, and the incidents recorded in the publications are just as disorganized and partial. Items in the internal newspaper, the Daily, are often anonymous and almost never representative of anyone but the writer. In general, the Daily staff printed whatever was submitted. Unattributed quotes, of which there are very many, come from “the man in the elevator.” Both spoken and written language often break into erratic “fucks” like flatulence. I’ve saved some for atmosphere, and deleted many for the sake of the air. Likewise with errors in typing, grammar, and spelling. Once the material is seen to be so loose that it hangs over all the edges in the English language, little is gained by reproducing every slip.

Unavoidably, interviews and scattered source papers select, almost randomly, some participants, and ignore others. The people who affected the community often did so without having any definable position, and often without having a name they cared to release. Rochdale prided itself on its brand of urban anarchy and its blunt democracy. This combination of anarchy, democracy, and secrecy allows no orderly retrieval of events, and permits no tidy history of leaders and individuals.

As well as de-emphasizing leaders, I have often had to leave aside another demand commonly made by a history: an accuracy that will stand up in court or classroom. Rochdale refuses to co-operate. As an example, Alex MacDonald, an articulate, alert former resident whom you will hear often in the pages to come, replied to a question about medical facilities by saying “there was a big — not one of those damn hippie street clinics — a fully functioning, three-room, eight-doctor clinic.” Eight doctors? That seems a lot. MacDonald shrugged: “I invented that number. Lots of doctors.” And when inventing doesn’t play with the facts, impairment might. As one interviewee put it: “I’ve destroyed my memory cells with acid and whiskey. A good combination.”

I am saved from one form of distortion, however, since none of this book is memoir. In 1973, I bought a loaf of raisin bread in the Etherea store at ground level as I passed through Toronto on my way to Europe, and that was as close to the living Rochdale as I came. For me, Rochdale did not need to be more than an idea. During the two years that I attended an experimental program at the University of British Columbia, Rochdale was the remote, full-scale example of what we were trying by half-steps.

Despite all the full-scale pain and confusion we are about to see, Rochdale was one of the brightest mindgames in a decade of mindgames, and none of it makes sense without a sense of fun. As longtime resident Bill King said, “It’s impossible to understand Rochdale without the boogie.”

![]()

2

An Ideal Beginning

The founders wanted a reputable name for a co-operative. They chose “Rochdale” in honour of an enterprise in 1844 in Rochdale, Lancashire, England. In that long-ago Rochdale, twenty-eight weavers, disciples of Robert Owen, had formed a co-op grocery on the ground floor of a cotton warehouse in Toad Lane. This prototype extended its alternative system into retailing, wholesaling, insurance, and welfare, all within twenty years.

The twentieth-century Rochdale might have lived twenty years as well and would be operating in Toronto today if the Rochdale building, as in the original plan, had become nothing more than a highrise housing students. The scale of the project was unusual, true, but large as it would be, it expected only to become a sober — and co-operative — university residence. Instead, in a moment of innocence, the building welcomed a passing spark, a quickening...