![]()

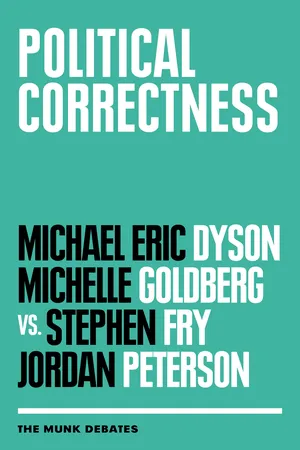

Pro: Michael Eric Dyson and Michelle Goldberg

Con: Stephen Fry and Jordan Peterson

May 18, 2018

Toronto, Ontario

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Ladies and gentlemen, welcome. My name is Rudyard Griffiths and it’s my privilege to moderate tonight’s debate.

I want to start by welcoming the North America–wide television audience tuning in right now across Canada on CPAC, Canada’s public affairs channel; across the continental United States on C-SPAN; and to those listening on CBC Radio’s Ideas.

A warm hello also to our online audience watching this debate — the over 6,000 streams active at this very moment — on Facebook Live, Bloomberg.com, and at Munkdebates.com. It’s great to have you as virtual participants in tonight’s proceedings.

And hello to you, the over 3,000 people who’ve filled Roy Thomson Hall for yet another Munk Debate. Thank you for your continued support of high-quality debates on the big issues of the day.

This debate marks the start of our tenth season, and we begin it missing someone who was vital to this debate series in every aspect. It was his passion for ideas, his love for debate, that inspired our creation in 2008, and it was his energy, his generosity, and his drive that were so important in allowing us to win international acclaim as one of the world’s great debating series.

His philanthropy, his legacy is remarkable. We all remember the $100 million donation to cardiac health here in Toronto last fall, which will transform the lives of millions of Canadians to come. We are all big fans and supporters of the terrific Munk School for Global Affairs and Public Policy on the University of Toronto campus, represented here tonight by many students in its master’s program. Congratulations to you. And also, we must recall what a generous endowment he made last spring to this series, one that will allow us to organize many more evenings like this, for many more years to come.

Now, knowing our benefactor as we do, we know that the last thing he’d want is for us to mark his absence with a moment of silence — that wasn’t his style. So let’s instead celebrate a great Canadian, a great life, and the great legacy of the late Peter Munk. Bravo, Peter!

Thank you, everybody. I know he would have enjoyed that applause. And I want to thank Melanie, Anthony, and Cheyne for being here tonight to be part of Peter’s continuing positive impact on public debate in Canada. Thank you for coming.

We have a terrific debate lined up for you this evening. Let’s introduce first our “pro” team, arguing for tonight’s motion, “Be it resolved, what you call political correctness, I call progress.” Please welcome to the stage award-winning writer, scholar, and broadcaster on NPR, Michael Eric Dyson.

Michael’s debating partner is also an award-winning author. She’s a columnist at the New York Times, and someone who is going to bring a very distinct and powerful perspective tonight, Michelle Goldberg.

One great team of debaters deserves another. Arguing against our resolution, “Be it resolved, what you call political correctness, I call progress,” is the Emmy Award–winning actor, screenwriter, author, playwright, journalist, poet and, tonight, debater, Stephen Fry.

Stephen’s teammate is a professor of psychology at the University of Toronto, a YouTube sensation, and the author of the international bestseller 12 Rules for Life. Ladies and gentlemen, Toronto’s Jordan Peterson.

On the way in this evening, we asked this audience of roughly 3,000 to vote on the resolution, “Be it resolved, what you call political correctness, I call progress.” Let’s see the results. The pre-debate vote: 36 percent agree; 64 percent disagree. So, a room in play.

Now, we also asked how many of you are open to changing your vote over the course of tonight’s debate. Are you fixed in your opinion, or could you potentially be convinced by one of these two teams to move your vote over the next hour and a half? Let’s see those numbers now: 87 percent said yes; 13 percent said no. So, a very open-minded crowd. This debate is very much in play.

As per the agreed-upon order of speakers, I’m going to call on Michelle Goldberg first for her six minutes of opening remarks.

MICHELLE GOLDBERG: Thank you for having me. As Rudyard knows, I initially balked at the resolution that we’re debating tonight, because there are a lot of things that fall under the rubric of political correctness that I don’t call progress. I don’t like “no-platforming” or trigger warnings. Like a lot of middle-aged liberals, I find many aspects of student social justice culture off-putting — although I’m not sure that that particular generation gap is anything new on the record about the toxicity of social media call-out culture, and I think it’s good to debate people whose ideas I don’t like, which is why I’m here.

So, if there are social justice warriors in the audience, I feel like I should apologize to you, because you’re probably going to feel that I’m not adequately defending your ideas. But the reason I’m on this side of the stage is that political correctness isn’t just a term for left-wing excesses on college campuses, or people being terrible on Twitter. I think it can be used, especially as deployed by Mr. Peterson, as a way to delegitimize any attempt for women and racial and sexual minorities to overcome discrimination, or even to argue that such discrimination is real.

In the New York Times today, Mr. Peterson is quoted as saying: “The people who hold that our culture is an oppressive patriarchy, they don’t want to admit that the current hierarchy might be predicated on competence.” That’s not particularly insane to me, because I’m an American and our president is Donald Trump, but it’s an assumption that I think underlies a world view in which any challenges to the current hierarchy are written off as political correctness.

I also think we should be clear that this isn’t really a debate about free speech. Mr. Peterson once referred to what he called “the evil trinity of equity, diversity, and inclusivity” and said: “Those three words, if you hear people mouth those three words, equity, diversity and inclusivity, you know who you’re dealing with and you should step away from that, because it is not acceptable.”

He argues that the movie Frozen is politically correct propaganda, and at one point he floated the idea of creating a database of university course content so students could avoid postmodern critical theory.

So, in the criticism of political correctness, I sometimes hear an attempt to purge our thought of certain analytical categories that mirrors, I think, the worst caricatures of the social justice Left that wants to get rid of anything that smacks of colonialism or patriarchy or white supremacy.

I also don’t really think we’re debating the value of the Enlightenment, at least not in the way that somebody like Mr. Fry, who I think is a champion of Enlightenment values, frames it. The efforts to expand rights and privileges, once granted just to landowning, white, heterosexual men, is the Enlightenment, or it’s very much in keeping with the Enlightenment. To quote a dead white man, John Stuart Mill: “The despotism of custom is everywhere the standing hindrance to human advancement.”

I think that some of our opponents, by contrast, bring challenges to the despotism of custom as politically correct attacks on a transcendent natural order.

To quote Mr. Peterson again, each gender, each sex, has its own unfairness to deal with, but to think of it as a consequence of the social structure — come on, really, what about nature itself? But there’s an exception to this, because he does believe in social interventions to remedy some kinds of unfairness, which is why in the New York Times, he calls for “enforced monogamy to remedy the woes of men who don’t get their equal distribution of sex.”

When it comes to the political correctness debate, we’ve been here before. Allan Bloom, the author of The Closing of the American Mind, compared the “tyranny” of feminism in academia to the Khmer Rouge, and he was writing at a time when women accounted for 10 percent of all college tenured faculty.

It’s worth looking back at what was considered annoyingly, outrageously, politically correct in the 1980s, the last time we had this debate. You know, not being able to call Indigenous people “Indians,” or having to use hyphenated terms, at least in the United States, terms like African-American. You know, adding women or people of colour to the Western Civilization curriculum, or not making gay jokes or using “retard” as an epithet. I get it: new concepts, new words stick in your throat. The way we’re used to talking and thinking seems natural and normal, by definition. And then the new terms, new concepts that have social utility, stick, and those that don’t fall away. If you go back to the 1970s, Ms. — you know, M-S, as an alternative to Miss or Mrs. — stuck around. And “womyn” with a y didn’t. And I hope that someday we’ll look back and marvel at the idea that gender-neutral pronouns ever seemed like an existential threat to anyone.

But I also don’t think it’s clear. That might not happen because, if you look around the world right now, there are plenty of places that have indeed dialed back cosmopolitanism and reinstated patriarchy in the name of staving off chaos. And they seem like terrible places to live.

I come from the United States, which is currently undergoing a monumental attempt to roll back social progress in the name of overcoming political correctness. And as someone who lives there, I assure you, it feels nothing like progress. Thank you.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Great start to the debate, Michelle. Thank you. I’m now going to ask Jordan Peterson to speak for the “con” team.

JORDAN PETERSON: Hello. So, we should first decide what we’re talking about. We’re not talking about my views on political correctness, despite what you might have inferred from the last speaker’s comments.

This is how it looks to me: we essentially need something approximating a low-resolution grand narrative to unite us. And we need a narrative to unite us because otherwise we don’t have peace.

What’s playing out in the universities and in broader society right now is a debate between two fundamental low-resolution narratives, neither of which can be completely accurate, because they can’t encompass all the details. Obviously human beings have an individual element and a collective element — a group element, let’s say. The question is, what story should be paramount? This is how it looks to me: In the West, we have reasonably functional, reasonably free, remarkably productive, stable hierarchies that are open to consideration of the dispossessed that hierarchies generally create. Our societies are freer and functioning more effectively than any societies anywhere else in the world, and than any societies ever have. As far as I’m concerned — and I think there’s good reason to assume this — it’s because the fundamental low-resolution grand narrative that we’ve oriented ourselves around in the West is one of the sovereignty of the individual. And it’s predicated on the idea that, all things considered, the best way for me to interact with someone else is individual to individual, and to rea...