![]()

Chapter 1

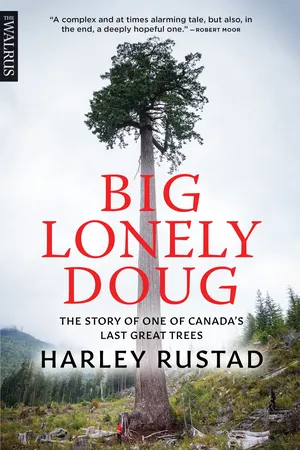

The Ribbon

On a cool morning in the winter of 2011, Dennis Cronin parked his truck by the side of a dirt logging road, laced up his spike-soled caulk boots, put on his red cargo vest and orange hard hat, and stepped into the trees. He had a job to do: walk a stand of old-growth forest and flag it for clear-cutting.

In many ways, this patch of forest was unremarkable. Cronin had spent four decades traipsing through tens of thousands of similar hectares of lush British Columbia rainforest, and had stood under hundreds of giant, ancient trees. Over his career in the logging industry, he had seen the seemingly inexhaustible resource of big timber continue to dwindle, and the unbroken evergreen that once covered Vancouver Island reduced to rare and isolated groves.

Known as cutblock number 7190 by his employer, one of the largest timber companies operating on the island, the twelve hectares represented a small sliver — around the size of twelve football fields — of the kind of old-growth forest that once spanned the island nearly from tip to tip and coast to coast. But this small patch of trees fringing the left bank of the Gordon River, just north of the small seaside town of Port Renfrew, was a prime example of an endangered ecosystem. Black bears and elk, wolves and cougars passed quietly under its canopy. Red-capped woodpeckers knocked on standing deadwood; squirrels and chipmunks nibbled on cones to extract seeds; and fungi the size of dinner plates protruded from the trunks of some of the largest trees in the world.

Cronin brushed through the salal and fern undergrowth, his jeans wet with dew that even during a hot summer forms every morning in these forests of perpetual damp. Underfoot, mounds of moss covering a thick bed of decaying tree needles were soft and spongy. Sounds don’t linger in these forests, arriving and dissipating quickly — absorbed by thicket and peat and mist before they’re allowed to swell. For now, the forest was still.

Cronin began the survey along the low edge of cutblock 7190, where he could hear the Gordon River thundering on the other side of a steep gorge. Come spring, salmon fry would be wriggling free of the pebbled river bottom and making their first swim downstream to open water; come fall, mature fish would hurl themselves upstream to spawn. The ancient trees, with their dense tangle of roots growing along the banks of the river, would filter out sediment and loose soil so that even during a rainstorm the forest kept the waters running clear.

As a forest engineer, Cronin’s job involved walking the contours of the cutblock, taking stock of the timber, and producing a map for the fallers to follow. At regular intervals of a couple dozen metres or so, he reached into his vest pocket for a roll of neon orange plastic ribbon and tore off a strip. The colour had to be bright to catch the eye of the fallers who would follow in the weeks or months to come. He tied the inch-wide sashes around small trees or the low-hanging branches of hemlocks or cedars to mark the edges of the cutblock. “FALLING BOUNDARY” was repeated along each ribbon. Timber companies in the province follow a forestry code stipulating that forest engineers must leave an intact buffer of fifty metres of forest up from a river, especially one that is known to be a spawning ground for salmon. Some engineers keep tight to those regulations to try to extract as much timber as possible from a given area. Known as “timber pigs,” they work the bush under a singular mantra: log it, burn it, pave it. The sentiment is twofold: ecology is secondary to economics, and these forests exist to be harvested. But Cronin was often generous with these buffer zones, leaving sixty to seventy-five metres — as much as he could without drawing the ire of co-workers or bosses.

There were trees of every age: a handful of exceptionally large cedars and firs, many younger and thinner hemlocks, and saplings filling in the gaps. The sun broke through the canopy in long beams that spotlit sword ferns and huckleberry bushes on the forest floor. Patches of lime-green moss turned highlighter-fluorescent in the sun. Scattered clouds broke an unusually clear blue sky; Cronin was more used to working amid thick mist and showers on winter days, emerging from a forest soaked and chilled.

Once the boundary of the twelve hectares was flagged with orange ribbon, Cronin criss-crossed the cutblock, surveying the pitches and gradients of the land. It was a slow task, clambering over slippery fallen logs and through thickets of bush. At one point, he climbed up onto a log to determine where a road could be ploughed into the forest. In many cutblocks, the first step in harvesting the timber is to construct a road — a channel through the bush where logs can be hauled, loaded onto trucks, and transported to a mill. It takes a specific skill to see through dense forest and haphazard undergrowth and plot a sure course that will allow for the safest and easiest extraction of logs. Maneuvering over undulating land layered with deadfall and vegetation, Cronin marked a direct line through the forest with strips off another roll of ribbon, this one hot pink and marked with the words “ROAD LOCATION.” He traversed any creek he came across and flagged it with red ribbon. When the flagging was done, the green-and-brown grove was lit up with flashes of foreign colour.

As Cronin waded through the thigh-high undergrowth, something caught his eye: a Douglas fir, larger than the rest, with a trunk so wide he could have hidden his truck behind it. He scrambled up the mound of sloughed bark and dead needles that had accumulated around the base of the giant tree.

Dennis Cronin looked up.

The tree dominated the forest — a monarch of its species. Its crown of dark green, glossy needles flitted in the breeze well above the canopy of the forest. Like many of the oldest Douglas firs he had come across in his career, the tree’s trunk was limbless until a great height. The species often loses the lower branches that grow in the shadow of the forest’s canopy. Many of these large and old Douglas firs have clear marks of disease, with trunks that are twisted and gnarled. This tree’s trunk sported few knots and a grain that appeared straight: it was a wonderful specimen of timber, Cronin thought.

With his hand-held hypsometer, a device to measure a standing tree’s height using a triangulation of measurements, Cronin took readings from the base and the top of the tree and estimated its stature at approximately seventy metres — around the height of a twenty-storey apartment building. Using a tape, he measured the tree’s circumference at 11.91 metres, and calculated the diameter to be 3.79 metres; if felled and loaded onto a train, the log would be wider than an oil tank car. The tree appeared just shy of the Red Creek Fir, the largest Douglas fir in the world, located a couple of valleys away. Cronin didn’t know it then, but he had not only stumbled upon one of the largest trees he had ever seen in his career — he had found one of the largest trees in the country. It was surely ancient as well, Cronin knew. A Douglas fir of such height and girth, growing in a wet valley bottom on Vancouver Island, could easily prove half a millennium in age. But to the experienced forester, this one looked much older. A thousand years? he wondered.

The logger could have moved on. He could have brushed his broad shoulders past yet another broad trunk and continued through the forest, leaving the giant fir to its fate. He could have walked through the undergrowth, across log and stream, to finish the job of mapping and flagging the cutblock. Fallers would have arrived; the tree would have been brought down in a thunderclap heard kilometres away, hauled from the valley, loaded onto logging trucks, and taken to a mill to be broken down into its most useful and most valuable parts.

Over forty years working on timber hauling crews and as a forest engineer, Cronin had accrued countless days working in the forests of Vancouver Island — he had encountered thousands of enormous trees over his career. But under this one, he lingered. He walked around its circumference, running his hand along the tree’s rough and corky bark. He looked up at a trunk so broad and straight it would hold some of the finest and most valued timber on the coast.

Instead of moving on, Cronin reached into his vest pocket for a ribbon he rarely used, tore off a long strip, and wrapped it around the base of the Douglas fir’s trunk. The tape wasn’t pink or orange or red but green, and along its length were the words “LEAVE TREE.”

![]()

Chapter 2

Evergreen

The western coastline of Vancouver Island ripples like the scalloped blade of a serrated knife, with hundreds of bays, harbours, and estuaries plunging deep into the island. Along the outermost fringe of the craggy shoreline, precariously perched on rocky points, little trees eke out an existence with roots in a crack of soil, bearing the full brunt of the near-constant lashing of storms off the Pacific Ocean. They cling to a life that never allows them to realize their full potential. Often, the side of the tree facing the turbulent water is entirely devoid of branches, or the trunk leans back from being relentlessly pushed by wind and spray. Even on a calm, clear day these small t...