- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

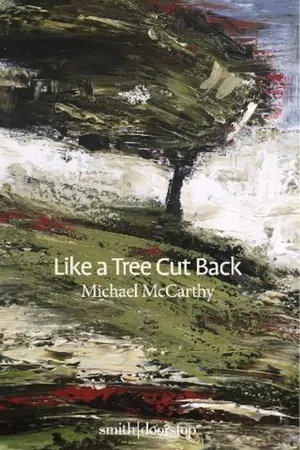

Like a Tree Cut Back

About this book

Like a Tree Cut Back weaves a memoir of Michael McCarthy from his boyhood in rural Ireland – overshadowed by an incident that resulted in the death of his brother – to his journey towards priesthood and poetry.

Interspersed throughout is a brief history of Carlow College, 19th Century Catholic Ireland's answer to Trinity College, Dublin, and – as McCarthy shows – a training ground for priests, apostles and rebels.

Part history, part memoir and part meditation, this outstanding book of poetry and prose confirms Michael McCarthy as a powerful storyteller and an acute observer of the human condition.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

RERAHANAGH

GROWING UP AMONG FERNS

THE ACCIDENT

It’s eleven o’clock on Saturday morning. But I don’t know this. The day and time are all the same to me because I’m only four.

Georgie Chambers is ploughing the big field at the cross. There is sudden commotion. My mother is shouting and she’s running out of the house. Something is after happening above on the road. My brother Ando is running after my mother. I’m running after my sister Nora. She’s heading for the house of our neighbours Danny and Mrs Mahony. I can’t keep up with her. Suddenly she’s not there.

I’m standing at the bend on the road at the top of the hill, and I can’t see where she has gone. What I can see is the way the grass covers the ditch. And the stones coming through the grass. I can see each individual stone clearly. I can see each bit of grass. I wait a long time. There is no sign of my sister. Something has happened, but it must have happened somewhere else.

I’m in the garden in front of the house. I’m looking through the gap in the hedge. I see my father walking slowly. He is carrying my brother James in his arms. Another man, taller than my father, is carrying my brother Tim. Tim is draped over the man’s shoulders. The man and my father carry the two of them into the house.

I’m sitting on the settle in the kitchen with my brother Ando. Something is going on below in the parlour. We’re not supposed to go down there. People keep coming from the parlour. They come through the kitchen, and out to the back kitchen and out the back door. My mother comes through with my uncle. My uncle has his arm around my mother’s shoulder. My mother is crying. Then my uncle goes back into the parlour. He comes out again. This time he has his arm around my father’s shoulder, and my father is crying.

My brother is counting people as they go past. Some of them are crying, and some of them are not crying. My mother is crying the most, then my father. My brother says he cried when he saw the cart turned upside down on the road. I didn’t cry at all.

My sister Kathleen comes home from school and she is crying. Danny Mahony is there, and Mary Jerry Connie, and the doctor, and the priest. Then my godfather Jerome comes in a motor car. People are taking pillows and a rug to the motor car. Jerome and my father take Tim away in the motor car, and everything is very quiet.

Georgie Chambers and his son are standing near the water tank at the gable end of the house. Georgie Chambers says it is a sad day. The two of them walk away from the house. They are carrying ploughing tackle: a horse’s collar and harness. The way they walk is what a sad day looks like.

My cousin Rosemary comes and my mother takes her upstairs. I follow them up. James is lying on the bed. He is not moving. He looks the same as a statue. I ask my mother why he looks like a statue. My mother says it is because he is in heaven. Rosemary starts to cry.

Mary Jerry Connie washes the blood out of the pillowcases. She cleans the house, dusting it and getting it ready for all the people coming. She washes the cups and saucers and the Holy Pictures. She is washing the statue of the Sacred Heart. I tell her: ‘Don’t tickle him neck.’

There are people and more people coming and coming. The house is full of people. There are many more people outside the house. Some of the people are in the shed where the cart with the broken shaft is. People are looking at the cart with the broken shaft. People are looking at the dents in the milk churns. People are telling each other what happened.

Everybody goes away and all the horse and carts go to the funeral. Mary Jerry Connie minds me and my brother.

Paddy and Liam come, and my father tells them for God’s sake to take away the black mare. A man comes to fix the shaft of the cart. He puts steel bands around where it is broken. The churns can’t be fixed. The dents will have to stay on them. The pillowcases are clean now, but you can see the marks where all the blood was.

People come to the house and say to my mother and father: ‘I’m sorry for your troubles.’ Whenever we say the rosary my father says we must pray for Tim in hospital, and poor James in heaven.

I hope Tim is having a nice time in hospital. I hope James is having a nice time in heaven. I think they should come home soon because everybody is lonesome. Everybody cries because they are lonesome. I am lonesome but I do not cry.

When we meet people in town, or after Mass, they come up to my mother and father and talk about poor James. They ask them how Tim is. My mother tells them he is in the Mercy Hospital. He has a fractured skull. The doctor says to be prepared for the worst.

After a long, long time my mother tells us that Tim is coming home from hospital.

My father has gone with Jerome in the motor car to bring him home. Everybody is very excited. When Tim arrives home he comes into the kitchen and everybody is laughing and crying, and fierce excited. I go all shy because I haven’t seen him for such a long time. I run and hide in the corner beside the dresser. I cover my face with my hands.

Tim says he has brought me a present but I’ll have to come and get it. I won’t come because I’m too shy. I peep out from between my fingers. I see that he has Cadbury chocolate bars. They are wrapped in purple and there is a big pile of them. I keep my face hidden in the corner, but in the end I stretch out my hands behind my back. Tim puts the chocolate bars into my hands and I run upstairs and begin eating them.

When Tim comes up to go to bed I hide my face under the clothes. I peep out now and then. I’m watching him, to see what he looks like. He pretends not to notice. After a while I get braver. And then I’m sitting up in the bed, looking across the room at him in the other bed. He begins talking and asking me questions. I start telling him the news, and about all the things that have been happening while he was in hospital.

Now when we meet people in town and they ask how Tim is doing, my mother and father say ‘he is doing fine, thanks be to God’. Then they talk about ‘the little boy’. They say they prayed for us. Sometimes they start crying. Sometimes my mother starts crying as well. Sometimes coming home from town in the trap my mother and father talk about poor James. Sometimes my mother starts crying again.

My brother Tim goes back to school. My father tells him to be very careful. He tells him to mind himself. Soon he is himself again. Soon he is riding horses again. My father is pleased to see him riding a horse. Seeing him on a horse frightens my mother.

My father and mother say James was an angel and that was why he went to heaven. Sometimes I wish he hadn’t gone to heaven. And sometimes I wish he’d come home.

Sometimes I wonder if I went to heaven would they be lonesome after me like they are after James. They keep saying that James was a good boy. I’m getting tired of everybody being lonesome for James and no one being lonesome for me.

THE BEDROOM

I climb the stairs, lingering as long as I can on each step. I examine the shine on the brass stair rods that I watched my sister polish, the way they neatly tuck into the tarpaulin. On the landing I look out through the back window. I see where the pigeons live in the trees. Beyond the trees, cattle are grazing in the fields that slope all the way down to the river. The summer sky is still a clear blue but I’ve been told it is past my bedtime.

To the left, three steps up and straight ahead, that’s my parents’ bedroom. To the right, three steps up and straight ahead, the girls’ bedroom. The door on the right, before the girls’ bedroom, is the boys’ bedroom. That’s where I’m heading because I’m a boy.

In our bedroom there are two double beds. My two brothers sleep in the bed at the far end. I share the bed nearest to the door with my uncle. I sleep on the inside, next to the wall. There are blankets and a patchwork quilt on each bed. My brother, one year older, will be sent to bed before too long. My brother, nine years older, won’t be coming to bed until much later. My uncle will come later still.

There is a curtain on the window but it is not drawn. I like to see the daylight for as long as I can. There is candle grease on the stone plinth at the bottom of the window. A leftover from the Christmas candle, when every window in Ireland has a candle in it so the Holy Family can find their way to Bethlehem.

The walls are painted yellow. The floor is covered in brown tarpaulin with faded yellow squares on it. A corner has curled up where the leg at the top end of the bed keeps getting pulled across it. There is a hole where the leg at the bottom of the bed has worn through. There are white enamel pots for peeing, with handles on them under each bed. There is a picture of the Sacred Heart on the wall.

The shape of the ceiling over the stairs protrudes between the beds, half dividing the bedroom. It gradually slopes upward and then has two steps at the top which are used as shelves. One has blankets on it. The other has a wooden money box my big brother made. It is painted green and nailed onto the shelf. There’s a lock on it but I know where he hides the key. My big brother has also invented an electric light for himself, a used radio battery with a piece of wire coming out of it. The wire is pinned along the groove of the shelf and attached to a bulb from a flash-lamp over the bed. There is a switch half way between the battery and the bulb. We’re not allowed to touch it because we’d only wear out the battery. Sometimes we switch it on when he’s not there.

Looking up at the white ceiling I trace the lines between the ceiling boards. Here and there I can see spaces between the boards. I try to see through these cracks, but it’s no good because it’s dark up there and all I see is the shadow of darkness. I wonder about the world up there because sometimes after dark I can hear mice running along the ceiling boards having fun. The sudden patter they make is like the patter of raindrops when it’s just starting to rain.

I like looking at the knots on the boards. They are still visible even though the ceiling has been painted many times over. These knots have interesting shapes. One looks like a spinning top. There is a small perfect roundness at its centre. I imagine it spinning, and decide that I’ll ask for a real spinning top for Christmas. Another one is the shape of a pear or a kangaroo depending on which way you look at it. Another has no shape at all that I can think of.

When my brother comes to bed we tell each other stories. I wonder out loud what else lives above the ceiling. What my brother is more concerned about are the creatures under the bed. The ones that come out in the middle of the night. He tells me how once he woke up to find his leg had slipped down inside the bed and something had got a hold of his foot. All he knew for certain was that his foot was ‘between teeth’.

My mother shouts up the stairs: ‘Will ye stop talking and go to sleep.’ We don’t take much notice. It’s hard to sleep on these long summer nights when it isn’t even dark yet. Later on, my father shouts: ‘Go to sleep this minute.’ That quietens us all right. In a while we begin to whisper again until eventually we drift off to sleep. Sometimes we are still awake when my big brother comes up. We watch him as he switches on his electric light to see if it is still working, and then gets into bed. Occasionally we are still awake when my uncle comes up. Sometimes we ask him questions and get him to tell us stories. He tells us the names of stars, and all about the Comet with its long bushy tail. It will be in the sky every night until it disappears, and then it won’t come back for another hundred years. My favourite thing in the sky is the Rory Bory Alice because it has such a nice name.

Sometimes gravity rolls me into the hollow in the middle of the bed and my uncle tells me to ‘push in out of that’. On one occasion when I’m a little older and he’s not in a good mood he says, ‘shove in will you. You’re taking up half the bed.’ I say: ‘Let you take up the other half.’ I overhear him later telling this story. It makes all the big people laugh. I realise everybody thinks I’m a very funny and clever boy. I like that.

My uncle gets up early to bring the cows in for milking. My big brother gets up a little later and goes out to the stall to milk. Sometimes I hear them and wake up. Sometimes I go back to sleep again. On a Saturday night my uncle shaves. He gets a basin of water, then rolls up his sleeves and stands in front of the shaving mirror. He dips the furry shaving brush into the basin, rubs the shaving stick on it and lathers up his face. Then he goes at it with his cut-throat. You can hear the scrape of the razor on his hairy stubble. He is very careful but sometimes he cuts himself. He puts little pieces of newspaper on his face to stop the bleeding.

When he’s finished shaving he spends a long time polishing his strong black shoes until he is entirely satisfied with the shine. On Sunday morning he gets up early for going to Mass. All he has to do is put on his shirt and tie and his blue suit, and then his socks and shoes. Sometimes he finds a hole in a sock and says: ‘Well blasht it for a story.’ The last thing he does is put on his bicycle clips, then he’s out the door and gone. We won’t see him again until dark night.

I’m supposed to be asleep while all this is going on, but the noise wakes me and I find it all very interesting. Once, I interviewed him.

‘Where are you going?’

‘I’m going to Mass.’

‘What are you doing?’

‘I’m putting on the style.’

‘What style?’

‘The style that Mary sat on.’

‘And did Mary sit on your style?’

There is a skylight out on the landing. You can see it through a space on the top corner behind the door. There is a similar space into the girls’ bedroom. Sometimes you can see their outlines reflected in the glass of the skylight.

When my other uncle the Priest comes to stay, things are rearranged. He sleeps in the girls’ room. A curtain is put across the boys’ room and the girls sleep in my brothers’ bed. My two brothers come in with me, and my uncle goes out to the hay shed. When this happens we have to be very quiet because my uncle is home from the missions and he finds it very hard to sleep. We can hear him saying his prayers. Sometimes he gets up in the middle of the night and goes out walking because he can’t sleep.

He tells us great stories about what China was like, and the different ways they had for torturing people. When he gives a sermon about it during Mass he gets very excited and shouts. All the big people talk about it afterwards and some of the women start crying and the men shake their heads in wonder. They give him money for the missions. He gets lots of letters from the postman and nearly all of them have money in them. My brother says he’ll be a priest too when he is big enough, and he’ll sit in the parlour all day reading letters and counting money. I want to be a priest too when I grow up because I was called after my uncle, and as well as having the same name we have the same birthday as well. He says I’m very clever and witty because the big people have told him what I said about the style that Mary sat on. I’ll be a priest for sure. Being in China is very exciting.

The other thing I remember about the bedroom is the day I got the measles. My big brother was putting up a wire fence and I was holding the bag of nails for him when I began to feel all funny. I could see the wind blowing through the grass like it often did but somehow it was different. It had a sort of yellow colour and it looked very hot. The next thing, I had pains in my legs. Marmalade was the cause of it. I could feel the briars from the marmalade inside in my legs and they were hurting me. I tried to explain to my mother but she just kept asking, ‘what marmalade are you talking about, child?’ I didn’t know what she meant because there was only one marmalade and the briars from it were hurting me inside in my legs. When the doctor came he lifted up my shirt. I was covered all over with spots. He said I had the measles and I’d have to stay in bed until I got better. He said the marmalade in my legs was only growing pains.

The last thing I remember about the bedroom is the day I ate my big brother’s sweets. He went to the fair with my father and after they had sold the heifers he bought some sweets for himself. I was busying around the bedroom minding my own business when I accidentally brushed up against his coat. I heard the rustle of the paper bag the sweets were in and I had a look in his pocket to see what sort of sweets they were. They were toffees. The wrapping paper had partly come off one of them and rather than going to all the trouble to wrap it up again I thought the best thing was to eat it. I put the ...

Table of contents

- COVER

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT

- DEDICATION

- CONTENTS

- PREFACE

- Part One: RERAHANAGH GROWING UP AMONG FERNS

- Part Two: BEYOND CHILDHOOD

- Part Three: A CHINK OF LIGHT

- Part Four: A TREE CUT BACK

- Part Five: MY JOURNEY OF CONVERSION

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Like a Tree Cut Back by Michael McCarthy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.