Chapter 1 introduces readers to the purpose and content of the book in addition to highlighting the central role professional ethics play as part of educators’ pre-service training guided by new standards developed and promulgated by the National Policy Board for Educational Administration known as the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders (PSEL). In discussing case law related to what is legal and what is ethical, important themes are organized that frame more specific content analysis in subsequent chapters. These themes are also apparent in educational literature that focuses on what constitutes good administrative practice. Students are at the center of this book and a primary focus of the professional standards.

Confronted with difficult situations, school leaders frequently rely on the rule of law to guide their work. On the other hand, many, if not most, of the situations that these educators face on a day-to-day basis require ethical rather than, or in addition to, legal decision making. This chapter focuses on school leaders’ recognition of ethical dilemmas and application of ethics in their professional decision making.

LAW, ETHICS, MORALS, AND VALUES

Educators, and many others for that matter, often confuse and intersperse terms such as law, ethics, morals, values, and personal preferences. Therefore, it is important to begin with some working definitions that should be helpful in sorting out these various concepts. Black, in his comprehensive legal dictionary (Garner, 2004), defines law as: “The regime that orders human activities and relations through systematic application of the force of politically organized society, or through social pressure, backed by force, in such a society; the legal system [as in] respect and obey the law” (p. 900). Thus, citizens are bound to obey laws or else face legal sanctions.

Both ethics and morals are defined as “custom or usage” and, in this respect, they are synonymous. Some philosophers, however, have drawn a distinction between the two. For example, Grenz and Smith (2003) conceptualize ethics as moral philosophy or “the division of philosophy that involves how humans ought to live” (p. 77). Ethics focuses on questions of right and wrong, what is humanly good, and why practices are moral or immoral. On the other hand, morality involves the actual process of living out these beliefs.

Perhaps more relevant to this discussion is the distinction between morals, values, and personal preferences. As Grenz and Smith (2003) point out:

Despite the affinity between the terms morals and ethics in philosophical treatments of the topic, in the media or in casual conversation, people today often distinguish between the two, so that morality comes to be linked to sentiments, personal preferences, or scruples. As a consequence, moralize is often used in a pejorative sense to refer to the attempt to inculcate one's own moral conclusions on others.

(Grenz & Smith, 2003, p. 77)

For the purposes of this book, the terms ethics and morals will be used in their true philosophical sense as distinguished from personal preferences or values. In no manner does this discussion support the imposition of any person's individual value system on others. Rather, the aim here is to understand the inherent limitations of the law in solving everyday problems, the broad discretion provided to school authorities by the judiciary, and the importance of self-reflection and inquiry in making ethical decisions that may, and often do, have a profound influence on students.

Unlike scholars (Begley, 2004) who see ethics as only a small part of a larger valuation process, something used mostly in times of high-stakes urgency, the premises here are that ethics should guide school leaders’ decision making, that there can be common ground even in a multicultural, pluralistic society, and that, rather than impose their own values on students and teachers, school leaders should strive to reach a higher moral ground in making decisions. This is not easy. As Shapiro and Stefkovich (2021) point out, ethical decision making involves reflection, an acknowledgment of various approaches to ethics, and constant self-assessment and reassessment. As Begley notes:

The study of ethics should be as much about the life-long personal struggle to be ethical, about failures to be ethical, the inconsistencies of ethical postures, the masquerading of self-interest and personal preference as ethical action, and the dilemmas which occur in everyday and professional life …

(Begley, 2004, p. 5)

ETHICS AND EDUCATIONAL LEADERS

In the past several decades, there has been recognition of the need, as well as increased demand, for courses in ethics for school professionals. Several educators have recognized the importance of developing educational leaders for ethical decision making (Beck & Murphy, 1994; Shapiro & Stefkovich, 2021; Walker, 1998). Campbell (1999) observes, “central to much of this literature is the argument that educational leaders must develop and articulate a much greater awareness of the ethical significance of their actions and decisions” (p. 152). Beck et al. (1997) refer to an “unprecedented amount of interest in explicit consideration of ethical issues by educators and students” (p. vii).

In the last 20 years, there has been a renewed interest in including ethics as part of educators’ pre-service training. Impetus for this movement came about after leaders in the field produced several books on this topic (Beck & Murphy, 1994; Noddings, 1992, 2003; Starratt, 1994, 2004). Interest increased exponentially after the Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium (ISLLC) released standards for the licensing of school administrators, which acknowledged ethics as a standard unto itself (Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium, 1996, 1998, 2008). Currently, new standards for the profession have been developed and promulgated by the National Policy Board for Educational Administration known as the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders (PSEL). Of particular importance is the order and sequence of these standards for the profession, both in policy, preparation and practice, for they “embody a research- and practice-based understanding” of the relationship between a holistic view of educational leadership and the valued aims of schooling that are realized in “promoting the learning, achievement, development, and well-being of each student” (NPBEA, 2015, p. 3). The standards represent a theory of action that guide practice and promote outcomes and are organized into four theory domains. The first of these domains consists of the following three standards: (1) Mission, Vision, and Core Values; (2) Ethics and Professional Norms; and (3) Equity and Cultural Responsiveness. Below is Standard 2 in its entirety as it currently reads: Effective educational leaders act ethically and according to professional norms to promote each student's academic success and well-being.

Effective leaders:

Act ethically and professionally in personal conduct, relationships with others, decision-making, stewardship of the school's resources, and all aspects of school leadership.

Act according to and promote the professional norms of integrity, fairness, transparency, trust, collaboration, perseverance, learning, and continuous improvement.

Place children at the center of education and accept responsibility for each student's academic success and well-being.

Safeguard and promote the values of democracy, individual freedom and responsibility, equity, social justice, community, and diversity.

Lead with interpersonal and communication skill, social-emotional insight, and understanding of all students’ and staff members’ backgrounds and cultures.

Provide moral direction for the school and promote ethical and professional behavior among faculty and staff.

(NPBEA, 2015, p. 10)

These standards are also reflected in a licensing exam for school leaders developed by the Educational Testing Service (ETS) and in college and university-based school leader education program requirements as set forth by agencies such as the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP) and its specialty area program, National Education Leadership Preparation (NELP).

THE LAW AND EDUCATIONAL LEADERS

School law courses remain a staple of many educational leadership programs. Law is also included in PSEL Standard 9, which states that:

Effective educational leaders manage school operations and resources to promote each student's academic success and well-being. Effective leaders: h) Know, comply with, and help the school community understand local, state, and federal laws, rights, policies, and regulations so as to promote student success.

(NPBEA, 2015, p. 17)

Treated in isolation, this preparation can create a tension for practitioners between the legal and moral aspects of school leadership. For example, there have always been actions on the part of school personnel that courts have ruled as legal, which other educators have criticized as unethical or simply bad practice.

These types of cases have long served as grist for vigorous debate, particularly in education law and policy classrooms. Part of this tension lies in the fact that courts have been hesitant to tie school officials’ hands when it comes to making decisions related to practice and thus have given practitioners considerable discretion in day-to-day decision making. These conflicts highlight the importance of legal and ethical decision-making models that allow educators to make informed choices about resolving problems in practice.

ETHICAL/LEGAL/EDUCATIONAL THEMES

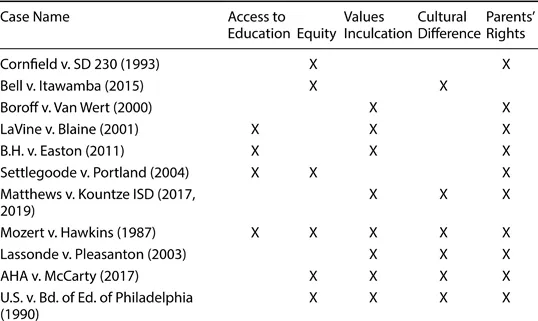

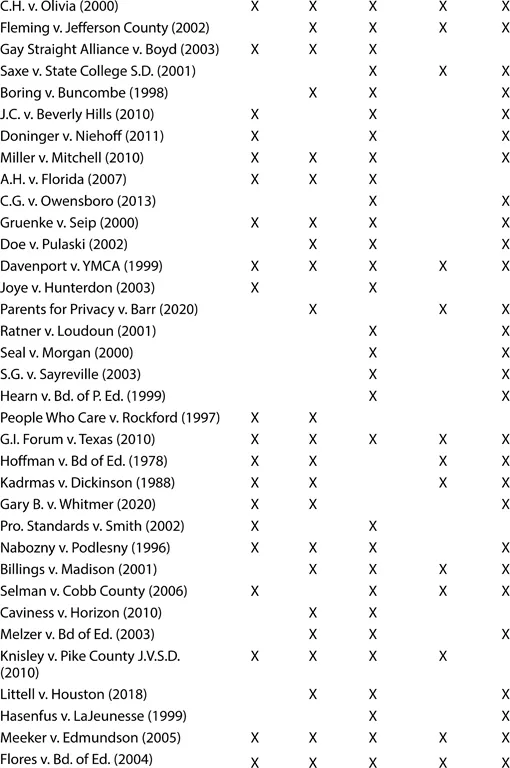

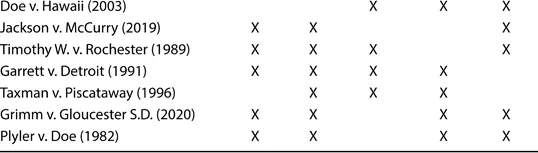

In discussing case law related to what is legal and what is ethical, important themes emerge. These themes are also apparent in educational literature that focuses on what constitutes good administrative practice. They include issues related to: (a) the importance of access to education for all students; (b) the tension between equality (treating all students the same) and equity (recognizing that students do not all start out as equal and some need more or different attention than others in acquiring an education); (c) the extent that schools inculcate values; (d) cultural differences in our ever-changing society; and (e) the rights of parents in relation to the school's responsibility to act in loco parentis (in the place of the parent). Table 1.1 presents these themes and their prevalence in the various cases.

Table 1.1 Ethical, Legal, and Educational Themes | |

REFERENCES

A.H. v. State of Florida, 949 So. 2d 234 (Florida Ct App. 1st Dist., 2007).

American Humanist Association v. McCarty, 851 F.3d 521 (5th Cir. 2017).

Beck, L. G., & Murphy, J. (1994). A deeper analysis: Examining courses devoted to ethics. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA, April.

Beck, L. G., Murphy, J., Mertz, N. T., Starratt, R. J., Shapiro, J. P., Stefkovich, J., & O’Keefe, J. (1997). Ethics in educational leadership programs: Emerging models. Columbia, MO: The University Council for Educational Administration.

Begley, P. T. (2004). Understanding valuation processes: Exploring the linkage between motivation and action. International Studies in Educational Administration, 32(2), 4–17.

Bell v. Itawamba County School Board, 799 F.3d 379 (5th Cir. 2015).

B.H. v. Easton Area School District, 725 F.3d 293 (3rd Cir. 2013).

Billings v. Madison Metropolitan School District, 259 F.3d 807 (7th Cir. 2001).

Boring v. Buncombe County Board of Education, 136 F.3d 364 (4th Cir. 1998).

Boroff v. Van Wert City Board of Education, 220 F.3d 465 (6th Cir. 2000), cert. den’d, 532 U.S. 921 (2001).

Campbell, E. (1999). Ethical school leadership: Problems of an el...