![]()

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION TO A TOUGH DILEMMA

Humanitarian assistance should reach the most vulnerable and needy, and be distributed to as many of them as possible. It must be impartial and neutral in a conflict in order to achieve this aim. This is the underlying theory of humanitarian efforts. In practice, however, taking the appropriate decisions to facilitate those ambitions is far more complex and difficult, especially when specific patterns of conflict apply.

This book is about a tough policy dilemma that may end up in a trap: how can political and humanitarian decision-makers alleviate human suffering to the largest extent possible in a brutal, asymmetric and intricate war without betraying the principles of impartiality, neutrality and of postulates of international legal frameworks in general? This contribution to the wider debate looks at the case of Syria in particular. Since the beginning of the popular uprising in 2011, within the wave of the Arab Spring protests, governments have struggled for answers on how to cope with this vast challenge on political, humanitarian and ethical levels.

On the conflict’s ninth anniversary in March 2020, the anti-government Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) announced that 226,247 civilians had been killed in the Syrian conflict, almost 30,000 of whom were children.1 According to this report, more than 88 per cent of those civilians had been killed by the Syrian regime2 and Iranian militias on the ground, and another 3 percent by Russian forces. Many of the victims were casualties of air raids; none of the armed opposition groups or even Islamist rebels ever held a plane or helicopter. By comparison, the so-called Islamic State (IS) killed 2.2 per cent of the civilian victims in Syria, and factions of the armed opposition, some 1.8 per cent.3

Over the same period to March 2020, the SNHR counted there had been 14,221 cases of torture, 98.8 percent of which had been perpetrated by the regime. Many Syrian citizens were tortured excruciatingly to death at the hands of their own government in a systematic manner, as evidenced by the Caesar Files of 2014, which contained photographic documentation of the cruelties, supplied by a defector from the military police.4 According to further SNHR data from March 2020, 146,825 people were listed as still detained or forcibly disappeared, exposed to horrendous conditions and torture, of whom 88.5 percent for account of the government side.5 In 2017, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al-Hussein, noted that: “[t]oday in a sense the entire country has become a torture-chamber; a place of savage horror and absolute injustice.”6

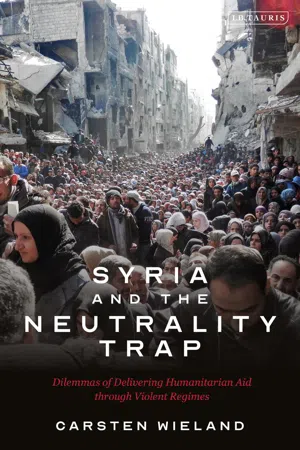

Due to the conflict, around 15 million Syrians have been forcibly displaced, seven to nine million of whom inside Syria, according to UNHCR or SNHR numbers.7 SNHR further reports that 853 medical personnel have been killed since 2011, mostly by regime forces and its allies Russia and Iran; 713 journalists have also died, with 80 per cent of these deaths being attributed to the regime. The human rights organization also found that 222 chemical attacks, 492 cluster bomb attacks, and 81,916 indiscriminate barrel bomb attacks had taken place. These are the most comprehensive statistics available to date.

It was not only the sheer quantity of death and suffering in Syria that challenged anybody’s imagination. How people died was also staggering. In terms of legal and political repercussions, the extent to which long-held principles of international humanitarian law (IHL) and international human rights law (IHRL) have been breached is extraordinary. The general rules for the treatment of civilians in wars, the Geneva Conventions, that most countries have signed up to (even Syria in 1953, although without the Additional Protocols), have been spurned either by those who have violated their content and spirit almost daily or by those whose imagination, energy or interest have become exhausted to adequately criticizing or sanctioning this behaviour. In addition, independent, impartial and neutral humanitarian assistance faced tremendous obstacles during the Syrian conflict, which in turn has triggered a highly controversial political debate about how to avoid blatant abuse in this and other conflicts to come.

“I have been working for more than twenty years in the humanitarian sector, in NGOs and then in the government, but I have never seen such a politicized humanitarian situation and complex challenge like that in Syria,” a German diplomat acknowledged to the author. “The Syrian conflict has left a strong imprint on humanitarian discussions in general.”8 A similar picture is conveyed by UN colleagues who concede that their humanitarian and protection mission in Syria is the most expensive, challenging and complex the United Nations has ever undertaken.9 Other international humanitarians – who had worked in various challenging contexts, including Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Yemen – say that the situation in Syria was among the worst in terms of restrictions on ability to operate.10 Another German diplomat who worked on humanitarian affairs in Geneva adds: “Human rights violations have always existed. But some twenty years ago in Sudan or Congo, the bombardment of hospitals, refusal of humanitarian access and so on were condemned much more harshly than today. IHL is on the retreat. This is a shocking development, and Syria is the main example.”11 In addition, the Norwegian Refugee Council and Oxfam, both of which have ample experience on the ground as registered international humanitarian organizations in Syria, conclude: “Syria is one of the most difficult contexts in the world in which to deliver principled humanitarian assistance.”12 And the French diplomat and think-tank member Charles Thépaut writes: “The humanitarian response in Syria is both a logistical masterpiece and an ethical conundrum.”13

It is particularly noteworthy that this development has occurred just when the growing pretensions of international human rights and humanitarian law have been regarded as far developed. However, after the disastrous US-led attack on Iraq, its equally disastrous post-war management from 2003 onwards and the controversial international intervention in Libya in 2011, the notion of an international Responsibility to Protect (R2P) has finally been buried under the Syrian rubble. For many Syrians, this was more than bad timing. Many of them originally took to the streets striving for dignity, personal freedoms, an end to arbitrary arrests and torture, and for better life perspectives, perhaps even democracy. International intervention to end the massive violence against civilians in a timely manner to protect human life before the crisis spread, radicalized and intensified, remained a pipe dream.

All of these dynamics evolved in a political macro-scenario in which the appetite of governments to become politically or militarily involved in the Syrian conflict to save lives was strongly limited for several reasons among European countries and the United States, under both the Obama and Trump administrations. The question that remained to be resolved inside Western foreign ministries was how to aptly respond to an escalating conflict with a high human toll within self-imposed limits of non-military action. In particular, Western decision-makers were split on what constituted legitimate and legally adequate means to alleviate human suffering but which would not be instrumentalized by parties to the conflict, including by a government that had violated its responsibility towards its own people to the worst possible extent.

Heated debates took place between those departments inside the foreign ministries that worked with a political focus on the Syrian conflict and those who were responsible for humanitarian issues. The same happened inside the UN itself. The respective camps had very different approaches given that their perspectives were often irreconcilable, almost by definition. This led to a great amount of frustration on both sides and to sometimes incoherent policy outcomes, especially when a third set of actors became active as well, namely those who approached the matter from a purely developmental and stabilization perspective. Thépaut points to a contradiction in this context:

The paradox is that U.N. assistance to Syrians is mostly funded by countries opposed to Assad. With a total contribution of $19 billion and $11 billion respectively since 2011, Europe and the United States provide around 90 percent of U.N. funding. However, key donors such as the U.S. Agency for International Development and the European Commission have been reluctant to push back against diversions of U.N. support to regime cronies and loyalists. They have likely feared being accused by humanitarian actors of politicizing assistance and did not want to weaken U.N. agencies further. They may have also feared the regime could react by further blocking assistance to non-loyalists.14

The traditional firewall between political and humanitarian decision-makers in ministries and international organizations exists for good reason. It is meant to prevent the risk of instrumentalizing and discrediting humanitarian principles. But the Syrian case has raised questions around whether this firewall was appropriate at all times and under all circumstances, and whether it really proved to be a bulwark for humanitarian impartiality and neutrality, all things considered. Alternatives are not easy to find and can be extremely risky while dealing with unscrupulous counterparts and when tough decisions must be taken on the ground. Protecting humanitarian principles and activities has become increasingly difficult in today’s complex and asymmetric wars.

The humanitarian Neutrality Trap means that decision-makers in donor governments may have good intentions when funding humanitarian assistance and when they insist on shielding this decision from political contexts and political deliberations. But if this humanitarian assistance, the way it is handled, ends up being distorted or abused on a large scale and if it actually turns into a convenient political and economic weapon used by a government at war against its people, that well-meant decision may do more harm than good. The trap snaps shut when: a) the concepts of impartiality and neutrality become a farce; b) purely humanitarian goals are not reached; c) the interventions end up prolonging the war and overall suffering; and, in the end, d) what was supposed to be an altruistic decision becomes merely dogmatic or even political in its own right in the absence of genuine neutrality in practice.

During the first years of this asymmetric conflict in particular, small NGOs tended to be dismissed by humanitarian decision-makers in Western ministries as ‘political’ actors since they were regarded as cooperating with insurgents. Somehow they managed to sneak into destroyed opposition areas in clandestine cross-border operations and constructed makeshift hospitals in basements on which bombs rained down. Meanwhile, UN organizations were by default regarded as neutral and impartial actors delivering assistance to Damascus – from where the helicopters, jets and missiles were launched. Such an approach had a legal foundation and followed international practice. However, this very practice came to be heavily tested in the Syrian conflict, and its legal foundations can be challenged, as we will see in the following chapters.

When an authoritarian regime loses control over its people and territory, one typical strategy it tends to apply is to insist even more on absolute national sovereignty in its external relations and – as we will see– with regard to the modalities of delivering humanitarian assistance. In such cases, the postulation of hard sovereignty compensates for the actual deficiency of sovereignty and bad government. Some elements of traditional international law can be used to support this claim, in theory. In practice, it also depends on the extent to which international supporters of a government as a warring party toe the line in this discourse or even shore up this claim by their words and deeds.

It was in this context of asymmetry of warfare and asymmetry of suffering that questions about cross-border delivery became increasingly urgent from a humanitarian perspective. Delivering aid cross line – i.e. from government-held territories to opposition territories – was frequently blocked by regime-backed authorities who had no interest in helping foster resilience in the areas they bombed. Equally difficult and controversial was the delivery of aid cross...