- 807 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

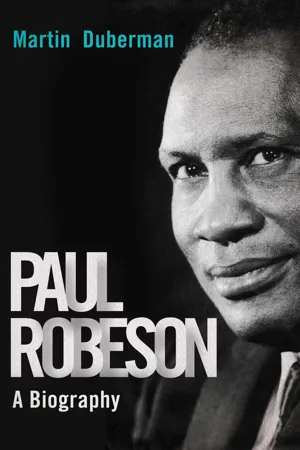

The remarkable life of Paul Robeson, quintessential Harlem Renaissance man: scholar, all-American, actor, activist, and firebrand

Born the son of an ex-slave in New Jersey in 1898, Paul Robeson, endowed with multiple gifts, seemed destined for fame. In his youth, he was as tenacious in the classroom as he was on the football field. After graduating from Rutgers with high honors, he went on to earn a law degree at Columbia. Soon after, he began a stage and film career that made him one of the country's most celebrated figures.

But it was not to last. Robeson became increasingly vocal about defending black civil rights and criticizing Western imperialism, and his radical views ran counter to the country's evermore conservative posture. During the McCarthy period, Robeson's passport was lifted, he was denounced as a traitor, and his career was destroyed. Yet he refused to bow. His powerful and tragic story is emblematic of the major themes of twentieth-century history.

Martin Duberman's exhaustive biography is the result of years of research and interviews, and paints a portrait worthy of its incredible subject and his improbable story. Duberman uses primary documents to take us deep into Robeson's life, giving Robeson the due that he so richly deserves.

Born the son of an ex-slave in New Jersey in 1898, Paul Robeson, endowed with multiple gifts, seemed destined for fame. In his youth, he was as tenacious in the classroom as he was on the football field. After graduating from Rutgers with high honors, he went on to earn a law degree at Columbia. Soon after, he began a stage and film career that made him one of the country's most celebrated figures.

But it was not to last. Robeson became increasingly vocal about defending black civil rights and criticizing Western imperialism, and his radical views ran counter to the country's evermore conservative posture. During the McCarthy period, Robeson's passport was lifted, he was denounced as a traitor, and his career was destroyed. Yet he refused to bow. His powerful and tragic story is emblematic of the major themes of twentieth-century history.

Martin Duberman's exhaustive biography is the result of years of research and interviews, and paints a portrait worthy of its incredible subject and his improbable story. Duberman uses primary documents to take us deep into Robeson's life, giving Robeson the due that he so richly deserves.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Paul Robeson by Martin Duberman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Boyhood

(1898–1914)

Princeton, New Jersey, at the turn of the century—and to some extent down to the present day—was known as the northernmost outpost of the Confederacy. Long before the Civil War, Southern aristocrats had enrolled their sons at Princeton University, considering it the only “safe” educational institution for those willing to venture north at all. Some Southern families even sent along—in one of those fits of inadvertent irony in which American history abounds—trusted black servants to insulate their scions from the potential hazards of an alien white culture. And thus from an early time the town of Princeton had a black population—and antiblack attitudes.

Even without the infusion of Southern aristocrats, Princeton had its own native tradition of hostility toward blacks, a hostility found in abundance everywhere in the country. By the early years of the twentieth century, that hostility was resurgent and the explicit Jim Crow principle in schooling, transportation, and restaurants had replaced even the marginal ambiguities of the post-Reconstruction period. Black teachers lost their jobs in integrated schools; black citizens were denied access to hotels; black workers were eliminated from trade unions. Social scientists in the universities (Franz Boas, the anthropologist, was among the notable exceptions) had begun bolstering the old doctrines of innate inferiority with their new “objective” expertise, uniting around the “scientific” doctrine that blacks were a separate species, one step above the ape on the evolutionary scale. Books appeared with such inflammatory, unapologetic titles as The Negro a Beast and The Negro: A Menace to Civilization. On the eve of World War I, the movie Birth of a Nation summarized the accumulated ideology and practice of the preceding two decades by portraying noble-hearted whites reluctantly taking the law into their own hands in order to curb the excesses of savage blacks—and was a resounding popular success. Rural areas of the South added burning at the stake to lynch law’s already potent arsenal of terror (there were more than eleven hundred lynchings of Southern blacks in the years 1900–14) and in the cities mob violence edged northward to explode with special ferocity in 1908 at Springfield, Illinois, the home of Abraham Lincoln.1

Physical intimidation was matched by political, social, and economic proscription. Between 1896 and 1915 every Southern state passed legislation decreeing white-only primaries, backed up by poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and literacy and property requirements that, taken together, effectively disenfranchised blacks. The federal government added its weight to the campaign to hold blacks in their “place.” Both Presidents Roosevelt and Taft, their policies differing in much else, combined in these years to sanction the prosecution and dismissal of black soldiers for responding to the violence directed against them by the townspeople of Brownsville, Texas. Woodrow Wilson, born in the South and elected to the presidency in 1912, continued the policies of his predecessors by extending segregation in federal office buildings and rebuffing black applicants for jobs.

At the turn of the century, Booker T. Washington was chief spokesman for his race, and blacks—at least in public and for white consumption—generally accepted his counsel for accommodation, conciliation, and deference. Washington defined economic rights for blacks as the right to be trained for low-paying jobs in factories and farms, cautioned patience in demanding political rights, and eschewed all interest in social intermingling. In the years immediately preceding World War I, both the militant “Niagara Movement,” spearheaded by W. E. B. Du Bois, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People would emerge to challenge Washington’s views, but in 1900 his philosophy held sway—and the escalation of white violence against blacks served notice that it could be overturned only at terrible cost.

Paul Leroy Robeson was born in the town of Princeton on April 9, 1898. His father, William Drew Robeson, had himself been born a slave, the child of Benjamin and Sabra, on the Roberson plantation in Cross Roads Township, Martin County, North Carolina. In 1860, at age fifteen, William Drew had made his escape, found his way north over the Maryland border into Pennsylvania, and served as a laborer for the Union Army (making his way back to North Carolina at least twice to see his mother). At the close of the Civil War, he managed to obtain an elementary-school education and then, earning his fees through farm labor, went on for ministerial studies at the all-black Lincoln University, near Philadelphia (receiving an A.B. in 1873 and a Bachelor of Sacred Theology degree in 1876). A classmate later described “the ‘Uncle Tom’ tendencies” among many of the students at Lincoln—but singled William Drew out as “among the notable exceptions.”2

While studying at Lincoln, William Drew met Maria Louisa Bustill, eight years his junior, a teacher at the Robert Vaux School. Her distinguished family traced its roots back to the African Bantu people (as William Drew did his to the Ibo of Nigeria), and in this country its members had intermarried with Delaware Indians and English Quakers. The many prominent descendants included Cyrus Bustill, who in 1787 helped to found the Free African Society, the first black self-help organization in America; Joseph Cassey Bustill, a prominent figure in the Underground Railroad; and Sarah Mapps Douglass, a founding member of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Louisa Bustill’s own sister, Gertrude, wrote for several Philadelphia newspapers and married Dr. Nathan Francis Mossell, the first black graduate of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine (as well as a considerable activist for racial justice). When Louisa Bustill married William Drew Robeson in 1878, the impressive legacy of Bustill achievements, past and current, became part of their son Paul’s heritage. But it was not the part he emphasized. He always identified more with the humbler lives on his father’s side, often alluding affectionately as an adult to his simple, good North Carolina kin—while scarcely ever referring to his Bustill relatives.3

At the time of Paul’s birth, his father was fifty-three years old and his mother forty-five. She had already given birth to seven children, five of whom had survived infancy. As the youngest, Paul was the doted-upon favorite, and in later life always spoke of his family with deep affection. The firstborn, William Drew, Jr., later became a physician in Washington, D.C., and died in 1925 at the youthful age of forty-four; Paul later credited him as the most “brilliant” member of the family and his own “principal source of learning how to study.” (William’s nickname among his contemporaries was “schoolboy.”) Marian, the one girl, became, like her mother, a teacher; Benjamin, like his father, went on to the ministry. The fiery Reeve (called Reed) rejected any traditional path or cautionary attitude; he was the family brawler, the boy who reacted to racial slurs with passionate defiance—and became something of an alter ego to his younger brother, Paul. “His example explains much of my militancy,” Paul wrote later in life. “He often told me, ‘Don’t ever take it from them, Laddie—always be a man—never bend the knee.’” As an adult, Paul would look back lovingly on his “restless, rebellious” brother, “scoffing at convention, defiant of the white man’s law.” But after street fights (Reed carried a bag of small, jagged rocks for protection) and brushes with the police, Reed was packed off to Detroit, became part owner of a hotel, apparently got involved in bootlegging and gambling, and is rumored to have died on Skid Row.4

The town of Princeton was a strictly Jim Crow place, with black adults held to menial jobs and black youngsters relegated to the segregated Witherspoon Elementary School (which ran only through the eighth grade; parents who wanted their children to have more education—like the Robesons—had to send them out of town). Emma Epps, a contemporary of Paul’s, remembers walking home with a pack of white kids at her heels yelling “Nigger! Nigger! Nigger!” Later in life, Paul scornfully rejected Princeton as “spiritually located in Dixie,” and he referred angrily to blacks living there “for all intents and purposes on a Southern plantation. And with no more dignity than that suggests—all the bowing and scraping to the drunken rich, all the vile names, all the Uncle Tomming to earn enough to lead miserable lives.” Still, the black community in Princeton was large (15–20 percent of the population) and cohesive, with a sizable contingent from rural North Carolina that continued in its Southern speech and traditions, and with Reverend Robeson’s relatives, Huldah Robeson, Nettie Staton, and cousins Carraway and Chance all living nearby. As Paul himself later wrote, blacks “lived a much more communal life” in Princeton “than the white people around them,” a communality “expressed and preserved” in the church.5

Within that church, Reverend Robeson was an admired figure. He had been pastor of the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church in Princeton for nearly twenty years when his son Paul was born in 1898. Of the three black churches in Princeton at the turn of the century, Witherspoon was the largest, the possessor of an auditorium, a parish house, and several additional properties, together valued at more than thirty thousand dollars. As pastor of Witherspoon, Reverend Robeson would later be recalled as having initially “made many improvements in the church methods and church property.” He would also be recalled, by blacks, as “ever the defender of justice—standing firmly for the rights of our race.” A contemporary commented that “you could move the Rock of Gibraltar” more easily—William Drew Robeson was made of “flintstone, unwilling to compromise on moral principles, even if it meant economic harm.”6

It did. After twenty years of service, Reverend Robeson was forced out of his Princeton pastorate. The initial charges against him focused on the inability of the Witherspoon Church to become financially self-sustaining. An investigating commission appointed by the Presbytery of New Brunswick reported in January 1900 that no misappropriation of funds had taken place but that there had been “great carelessness” in keeping business records. Finding insufficient improvement six months later, the commission recommended “the dissolution of the Pastoral Relation existing between Rev. William D. Robeson and said Church.” No reasons were given, and no charges, or even intimations, were made against Reverend Robeson’s character. Seventy-two members of the Witherspoon Church—including all three of its Elders and three of its four Trustees—promptly petitioned against his discharge. Reverend Robeson himself, in a lengthy speech before the Presbytery, “made an eloquent appeal” (according to the local press) in his own behalf. He “intimated that the Presbytery was inclined to be hard on him and his church because colored.” The chairman of the investigating commission replied that “if Mr. Robeson had been a white pastor, Presbytery would have dissolved the relation long before this,” and declared that “there is a misfit at the Witherspoon Street Church and that it is useless for Mr. Robeson longer to continue in that field.”7

Further discussion before the full Presbytery “brought out the fact that Mr. Robeson had been kind to his people, administering to the wants of the most needy in times of their suffering out of his own substance, often thereby imperilling his own financial interests and bringing upon himself the very conditions which formed the basis of some complaints made against him.” With “neither pastor nor people” asking for a dissolution and with Reverend Robeson’s character having been shown to be “above reproach,” the Presbytery—for the moment—decided that the commission’s suggestion for separation was not “sustained by facts necessary to warrant a recommendation of such grave moment.” It voted to recommit the report and instructed the commission to provide concrete reasons for its view that Reverend Robeson’s pastoral relations with his church should be severed.8

The commission’s animus was only momentarily deflected. According to the later testimony of two contemporaries, Reverend Robeson had gotten “on the wrong side of a church fight,” having apparently refused to bow to pressure from certain white “residents of Princeton” that he curtail his tendency to “speak out against social injustice” in the town. Many years later, after Reverend Robeson’s son Paul (still a toddler at the time of his father’s troubles) had himself become the target of public abuse, a family friend from the early days commented on how Paul’s “ideas, thoughts and effort were misinterpreted by the white man to keep his black brother in the dark and keep us from making progress,” adding, “They did it to his father.”9

The commission went back into session and in October 1900 issued a “supplemental report” testy in tone and adamant in its recommendation that Reverend Robeson be separated from his pastorate. Forced this time to assign reasons, the commission mostly resorted to vague charges about a falling-off in membership at the Witherspoon Church and a “disrelish” for its services “as at present conducted.” In further alluding to “a general unrest and dissatisfaction on the part of others”—meaning white residents of Princeton—“who have been the Church’s friends and helpers,” the commission tipped its actual hand, for the “lack of sympathy” toward Reverend Robeson that it cited could not have referred to his own black congregation. On the contrary, its members, meeting several times under the independent auspices of a white faculty member from the Princeton Seminary, spoke out forcefully and voted nearly unanimously in favor of retaining Reverend Robeson as pastor.10

That made no impression on the commission. The “welfare and prosperity” of the Witherspoon Church, it announced, would be “greatly enhanced” by Reverend Robeson’s departure. Bowing to the commission’s intransigence, William Drew Robeson resigned, effective February 1, 1901. His salary (about six hundred dollars a year) and his use of the pastor’s residence were continued until May 1. On January 27, 1901, the day of Reverend Robeson’s farewell sermon, chairs and benches had to be placed in the aisles to accommodate the overflow crowd, and many stood at the rear of the church. He began by acknowledging that “I have made some mistakes and committed some blunders, for I am human and faulty; but if I know my own heart, I have tried to do my work well.” Throughout his speech he made only one oblique reference to those who in the church’s “darkest need forsook it,” but otherwise advocated “forgetting the things that are behind.” With the largeness of spirit that his son Paul would always admire and emulate, Reverend Robeson eschewed any desire “to recriminate and rebuke.” “As I review the past,” he said, “and think upon many scenes, my heart is filled with love.” He closed by urging his congregation, “Do not be discouraged, do not think your past work is in vain.” The words would prove emblematic for his son Paul’s own life.11

Within just a few years of losing his pastorate, Reverend Robeson had to face a second, more devastating tragedy. His wife, Louisa, had long been afflicted with impaired eyesight and ill health. When, on a wintry day in 1904, a coal from the stove fell on her long-skirted dress, she failed to detect it. Fatally burned, she lingered on for several days in great pain. Paul, not yet six years old, was away at the time of the accident, but his brother Ben was home. Throughout Ben’s life, according to his daughter, the mere sight of a flame was enough to upset him.12

As an adult Paul claimed to have scant memory of his mother—perhaps a predictable effect of trauma. Yet he did several times confide to intimates, “I admired my father, but I loved my mother,” and he had a vivid recall of the day of her funeral: “He remembers his Aunt Gertrude taking him by the hand, and leading him to the modest coffin, in the little parlor at 13 Green St.—to take one last, but never forgotten look at his beautiful, sweet, generous-hearted Mother.” Otherwise, Louisa Bustill Robeson is barely present in the historical record; a scattered reference or two hint at a woman of considerable intellect and education (she wrote many of her husband’s sermons and is also recalled as a “poetess”), generous toward those in need, strong yet gentle—a temperament much as her son’s would be.13

The Bustill clan showed disinterest in the “dark children” Louisa had left behind (she herself had been light-skinned and high-cheekboned, reflecting the mix of African with European and Delaware Indian heritage), which was perhaps another reason Paul identified deeply with his father’s uneducated relatives, who treated him with unfailing kindness. Reverend Robeson, bereft of his pastorate and his mate, struggled to regain his balance. He was occasionally called on to give a sermon in this church or that, but to piece out an income he became a coachman, driving Princeton students around town, and in addition got himself a horse and wagon to haul ashes for the townspeople (the ashes, Paul later recalled, “piled up in the back yard in such mass as if one were looking at a coal heap in the Rhonda [sic] Valley in Wales …”). “Never once,” Paul remembered, did Reverend Robeson “complain of the poverty and misfortune of those years.” He retained “his dignity and lack of bitterness.” But for a time he could barely sustain a livelihood. The Princeton Packet, wanting in all other news about blacks, printed a notice that William Drew Robeson owed $12.25 in unpaid taxes on his house.14

At the time of their mother’s death in 1904, Ben and Paul were the only children still at home (Marian, next youngest to Paul, was staying with relatives in North Carolina and studying at the Scotia Seminary for young black women). It wasn’t until 1907 that Reverend Robeson managed to relocate himself and his two sons in the town of Westfield, but even then economic hardship continued. Reverend Robeson worked in a grocery store, slept with Paul and Ben in the attic under the roof of the store, cooked and washed in a lean-to attached to the back of the building. Shifting his denominational affiliation from Presbyterian to African Methodist Episcopal, he somehow managed to build a tiny church, the Downer Street St. Luke A.M.E. Zion (Paul and Ben helped lay the first bricks “in this Pillar of Zion”), and to hold together its flock of rural blacks from the South. They, in turn, helped Reverend Robeson hold together his family. The woman who ran the grocery store downstairs...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Boyhood (1898–1914)

- Chapter 2 Rutgers College (1915–1918)

- Chapter 3 Courtship and Marriage (1919–1921)

- Chapter 4 Provincetown Playhouse (1922–1924)

- Chapter 5 The Harlem Renaissance and the Spirituals (1924–1925)

- Chapter 6 The Launching of a Career (1925–1927)

- Chapter 7 Show Boat (1927–1929)

- Chapter 8 Othello (1930–1931)

- Chapter 9 The Discovery of Africa (1932–1934)

- Chapter 10 Berlin, Moscow, Films (1934–1937)

- Chapter 11 The Spanish Civil War and Emergent Politics (193 8–1939)

- Chapter 12 The World at War (1940–1942)

- Chapter 13 The Broadway Othello (1942–1943)

- Chapter 14 The Apex of Fame (1944–1945)

- Chapter 15 Postwar Politics (1945–1946)

- Chapter 16 The Progressive Party (1947–1948)

- Chapter 17 The Paris Speech and After (1949)

- Chapter 18 Peekskill (1949)

- Chapter 19 The Right to Travel (1950–1952)

- Chapter 20 Confinement (1952–1954)

- Chapter 21 Breakdown (1955–1956)

- Chapter 22 Resurgence (1957–1958)

- Chapter 23 Return to Europe (1958–1960)

- Chapter 24 Broken Health (1961–1964)

- Chapter 25 Attempted Renewal (1964–1965)

- Chapter 26 Final Years (1966–1976)

- Acknowledgments

- Note on Sources

- Notes

- Index

- Textual Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright Page