- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An intimate depiction of the visionary who revolutionized the art world

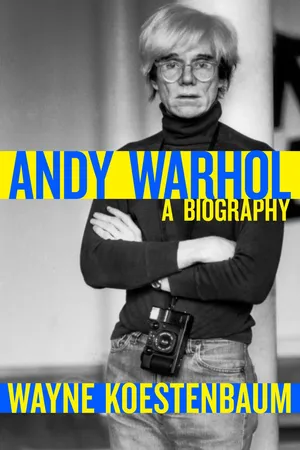

A man who created portraits of the rich and powerful, Andy Warhol was one of the most incendiary figures in American culture, a celebrity whose star shone as brightly as those of the Marilyns and Jackies whose likenesses brought him renown. Images of his silvery wig and glasses are as famous as his renderings of soup cans and Brillo boxes—controversial works that elevated commerce to high art. Warhol was an enigma: a partygoer who lived with his mother, an inarticulate man who was a great aphorist, an artist whose body of work sizzles with sexuality but who considered his own body to be a source of shame.

In critic and poet Wayne Koestenbaum's dazzling look at Warhol's life, the author inspects the roots of Warhol's aesthetic vision, including the pain that informs his greatness, and reveals the hidden sublimity of Warhol's provocative films. By looking at many facets of the artist's oeuvre—films, paintings, books, "Happenings"—Koestenbaum delivers a thought-provoking picture of pop art's greatest icon.

A man who created portraits of the rich and powerful, Andy Warhol was one of the most incendiary figures in American culture, a celebrity whose star shone as brightly as those of the Marilyns and Jackies whose likenesses brought him renown. Images of his silvery wig and glasses are as famous as his renderings of soup cans and Brillo boxes—controversial works that elevated commerce to high art. Warhol was an enigma: a partygoer who lived with his mother, an inarticulate man who was a great aphorist, an artist whose body of work sizzles with sexuality but who considered his own body to be a source of shame.

In critic and poet Wayne Koestenbaum's dazzling look at Warhol's life, the author inspects the roots of Warhol's aesthetic vision, including the pain that informs his greatness, and reveals the hidden sublimity of Warhol's provocative films. By looking at many facets of the artist's oeuvre—films, paintings, books, "Happenings"—Koestenbaum delivers a thought-provoking picture of pop art's greatest icon.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

The Sixties

3. Screens

HOW DID ANDY WARHOL become a painter? One answer he concocted: “When I was nine years old I had St. Vitus Dance. I painted a picture of Hedy Lamarr from a Maybelline ad. It was no good, and I threw it away. I realized I couldn’t paint.” That flip response diverts attention from his secret seriousness; his verbal deflections are always deep. Paradox: Warhol was not a painter, although he painted.

The story of how he became—sort of—a painter is mechanical and oft repeated (it is well told in David Bourdon’s monograph) and so can be dispensed as automatically as a tuna sandwich from an Automat. More heartfelt is the tale of the human relations behind the Pop paintings—intimacies that spring to life in his films. Each painting, too, reveals a friendship, betrays an interaction, transmits a newsflash of interpersonal desire. Whether his subject is soup, a HANDLE WITH CARE—GLASS—THANK YOU label, S&H Green Stamps, dollar bills, or do-it-yourself paint-by-number art kits, each canvas asks: Do you desire me? Will you destroy me? Will you participate in my ritual? Each image, while hoping to repel death, engineers its erotic arrival.

At the beginning of the 1960s Andy Warhol decided again to be a painter. For subjects, he chose comic strips, advertisements: Popeye, Nancy, Coca-Cola, Dick Tracy, Batman, Superman—images of childhood heroism, thirsts quenched, fantastically draped he-men standing up to insult. He told superstar Ultra Violet one origin of this iconography: “I had sex idols—Dick Tracy and Popeye. … My mother caught me one day playing with myself and looking at a Popeye cartoon. … I fantasized I was in bed with Dick and Popeye.” His dilemma—a pretend conflict?—was whether to render these figures expressionistically with drips and overt signs of the hand, or flatly, without personality. He showed his paintings to curators and dealers, and solicited opinions about the direction his work should move—toward “feeling” (wild marks), or toward “coldness” (mechanical reproduction).

One consultant was filmmaker Emile De Antonio, nicknamed “De.” Sometime in 1960 (the date is uncertain), according to Warhol and Pat Hackett’s memoir of the period, POPism, he showed De two renderings of a Coca-Cola bottle, and asked which he preferred. One was “a Coke bottle with Abstract Expressionist hash marks halfway up the side.” The other was “just a stark, outlined Coke bottle in black and white.” De pronounced the expressionist version crap and the mechanical version a masterpiece, and so Warhol, for years, avoided painterly stigmata and strove for machinelike execution.

The term Pop does not adequately explain Warhol; although he used popular and commercial images for his silkscreened paintings of the early 1960s, each has a clear link to his own body and history. He profited from the term Pop, but he didn’t believe in it: he casually defined it as a way of “liking things.” As a commercial artist in the 1950s, his task was to make the public like the objects he drew, enough to buy the products. Andy liked a promiscuous gamut of objects: men, stars, supermarket products. He liked zing, oomph, vim, pizzazz—any hook, whether ad or accident, that could rivet the eye by exciting or traumatizing it. Such images included disasters, and so he painted car wrecks, electric chairs, race riots: scenes you couldn’t bear to ignore because they aroused unholy fascination, what Freud described as unheimlich. Warhol appreciated any immediately recognizable image, regardless of its value. In 1963, when he began wearing a silver wig, his own appearance (documented in self-portraits) acquired the instantaneous legibility that he demanded of Pop objects.

Ashamed of his appearance, or wishing to spin it as performance, he covered his face with a theatrical mask when Ivan Karp, scouting for the Leo Castelli Gallery, came to call in 1961. Karp remembers that the artist in his studio was loudly playing the Dickie Lee song “I Saw Linda Yesterday” over and over: Andy claimed not to understand music until repetition drummed its meanings in. Henry Geldzahler, an associate curator at the Met, accompanied Ivan one day; Henry would become a staunch ally, although later he would alienate Andy by not including him in the 1966 Venice Biennale. Irving Blum and Walter Hopps from Los Angeles’s Ferus Gallery also visited, and eventually gave Andy his first solo painting show.

At first, however, no one accepted or exhibited his paintings. Leo Castelli already represented Roy Lichtenstein, committed to comics, and Castelli deemed that one Pop artist was enough. Andy showed paintings for the first time not in a gallery but in a Bonwit Teller window, in April 1961: with this gesture, he paid dual allegiance to commerce and art—a split he hardly took seriously, though pundits did—and proved that his work could roost in clothing stores, those feminine bazaars of fetish and decor.

More mysterious than how Andy became a painter, or why he chose to paint comic-book and commodity images (perhaps he calculated that these American objects and icons were a safely majority taste, while the naked men and shoes he’d rendered in the 1950s were a minority taste), is why he became a painter at all. He’d always wished to express his body, to push it through a silken mesh of given images; he’d always wanted to be a “fine” (classy) artist, and had merely been biding his time. His sketches and presentation books had a limited audience; he knew that painters were more famous than commercial or coterie artists. He took inspiration from the careers preceding and surrounding him—Jackson Pollock made a splash in Life magazine in the late 1940s, and Andy’s peers Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg had recently arrived. Andy bought a Johns drawing of a lightbulb and was desperate to be noticed by Johns and Rauschenberg, lovers who kept their sexual identities under wraps. Andy was too fey in manner, as he admits in his memoirs, to hide his homosexuality, and De Antonio told him that the reason Johns and Rauschenberg avoided him at parties (and mocked him behind his back) was that Andy was too effeminate, and that his swish conduct threatened to rock the boat they were trying manfully to row toward success. In praise of what he could not embody, in 1962 and 1963 Andy did two silkscreen paintings of Rauschenberg, one titled Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, in which he pictured his peer as heroic artist, epitome of rugged pioneer self-made masculinity—a cowboy, or at least a dreaming farmhand. Eventually Rauschenberg and Warhol became grudging acquaintances (photos of the two embracing in the 1970s reveal the limits of their mutual affection), and Warhol’s fame (though not his reputation among influential critics) trumped Pollock’s. Warhol’s decision to become a painter in the first place was an attempt to queer the Pollock myth—to prove that art stardom was a swish affair: all this business of men dripping paint on floors and posing in T-shirts and khakis in barns! The desire to be like a man—to be a painter like Pollock—was a project in resemblance, in imitation: not to be a master, but to be like a master, and thereby to master mastery.

Pollock’s champion in the early 1960s was Frank O’Hara, the insouciant, nervy poet and curator at MoMA, which as early as 1958 had proclaimed its indifference to Warhol by refusing the donation of one of his shoe drawings. Warhol admired and envied members of the aesthetic gay intelligentsia—Rauschenberg, Johns, and O’Hara key among them—and he attempted to court O’Hara, although O’Hara disliked Warhol’s work and only came around to an appreciation of it a year or so before his own untimely accidental death in 1966. According to O’Hara’s biographer Brad Gooch, Warhol sought the good graces of the smart gay set: “Warhol gave O’Hara an imaginary drawing of the poet’s penis, which he crumpled up and threw away in annoyance.” (Recall that Garbo, too, had crumpled one of Andy’s drawings.) Warhol wanted to draw O’Hara’s feet: the poet declined the offer.

Andy’s breakthrough as an artist came in 1962, and it had nothing to do with O’Hara, who I wish had shown more tolerance for the pasty-faced, unlettered Mr. Paperbag, whose art had affinity with such O’Hara gems as “Lana Turner has collapsed!” and “To the Film Industry in Crisis.” In August 1962 Andy began photosilkscreening, commencing with a baseball player and then actors Troy Donahue and Warren Beatty. (Although his portraits of Liz and Marilyn earned him the most fame, he preceded female deities with male; his goddesses, not intrinsically women, may indeed be men at one remove.) On August 5, Marilyn Monroe fatally overdosed, and the very next day he silkscreened her needy face. Dead, she begged for respectful (handle-with-care) replication. Andy held that Marilyn desires or deserves no image but her own, a death row of doubles, or a single face enshrined in a godless, lonely field of gold. Andy also began silkscreening fatalities: he had already painted a disaster, apparently at Geldzahler’s suggestion—depicting the front page of the New York Mirror, June 4, 1962, the headline reading “129 Die in Jet.”

Silkscreening allowed him to appropriate an image—publicity still, press clipping. A shop printed a negative of the Warhol-chosen photo on a screen, through which Andy and an assistant pushed paint to form a positive image on canvas. Sometimes he first hand-painted color zones or primed the entire canvas, and then screened the image on top. Silkscreening, faster and easier than painting, removed the obligation of using the hand; silkscreening undercut (and poached on) photography’s claims to depict the real. And silkscreening required a historically new variety of visual intelligence—a designer’s or director’s, perhaps, rather than a conventional painter’s. Andy had a clairvoyant sense of what subjects were worth copying; he had an iconoclastic notion of what surprising colors should garnish or offend the bare black-and-white image, and what blues or reds or silvers had the power to verify and ratify the self who gazed at them; and he knew precisely what cockeyed rhythms of repeated images could defamiliarize received truths. He had a crush on hazard and flaw—places where the screen slipped or got clogged with paint, moments where the image was smudged or not fully applied, or where one image accidentally overlapped and screwed up the clarity of another. He had hand-painted his earliest Pop works from projections or with stencils, but in silkscreening he was jubilant to discover an efficient way of making paintings that were virtually photographs, illicitly transposed—smuggled across the hygienic border separating the media.

Silkscreens—baffles—introduced distance between himself and the viewer. Literally, silkscreens were nets, webs, mazes—crisscrossing meshes, composed of silk (the stuff of fine clothing, especially women’s wear); and thus his beloved silkscreens were structures of enchainment and enchantment, poised between spider’s web and widow’s veil. In the 1950s, Andy had painted folding screens, one in collaboration with his mother: it was festooned with the numerals 1 through 9, as if intended to teach schoolchildren how to count. An undressing body could hide behind a folding screen’s ersatz wall; one imagines modest Andy changing outfits behind its zigzag barrier. Screens, like fences between fractious homesteaders, made good neighbors. Andy, who chose not to screen out information (words and pictures rushed pell-mell into his consciousness), doted on screens because they were antidotes to his unscreened, hyperaesthetic constitution. As objects, they were heavy to draw across a canvas; he needed an assistant. Silkscreening resembled weight lifting: a dapper physical act. Art’s ulterior motive, for Warhol, became the pleasure of watching the strong-muscled assistant work. He was Andy’s screen: the two of them together, forcing paint through the silk mesh, came closer than artist and helper otherwise might. Art screened their intimacy.

Andy had his first solo painting show in 1962, in Los Angeles, at the Ferus Gallery (he didn’t attend): it consisted of thirty-two individual Campbell soup cans, each a different flavor. Each painting was the same; only the label’s words varied. Difference, not a visual affair, lay in semantics, gustation: Cream of Asparagus was not Cream of Celery, and Green Pea was not Bean with Bacon. The sequence’s deadpan effrontery made Andy famous, and news magazines anointed Pop art a trend. He had his first New York show, at Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery, that same year: he showed Marilyns, Elvises, and disasters. He was pursuing two parallel iconographic missions, stars and disasters. The two overlapped: stars interested him when they died (Marilyn), when they hung on the verge of death (Liz), when they inflicted death (Elvis with pistol), or when they threatened Andy-the-viewer with orgasmic death. Deaths of anonymous people intrigued him because he believed people should pay attention to the nonstellar and thereby give them a soupçon of fame. To be famous, for Warhol, was merely to be noticed, turned on, illuminated; to bestow fame was charity, like feeding a neglected child. His goal was to make everyone famous—the creed of “Commonism,” Andy’s revision of communism. He believed himself “com-monist,” not Pop—he wanted to place glamour communion on the tongues of the world’s fame-starved communicants.

In 1963, Warhol had forged himself into a painter, but his story would be less melodramatic if he had remained merely a painter, a vocation that never captured his undivided attention; it has been a lasting public misperception that he primarily painted. In 1963 he ventured into two alternative spheres. The first realm was spatial, interactive: he created his first Factory—studio, party room, laboratory for cultural experiment. The second realm was cinematic: he bought a 16mm Bolex camera and made his first film. And though he essentially stopped moviemaking at the end of the 1960s but continued painting for the rest of his life, his movies are as important as his canvases to American art history, and deserve equal consideration. He removed the films from circulation in 1972; for a generation they have been absent from public view. Now they are being systematically restored. In coming years, as more people watch them, his complex achievement as filmmaker will challenge the limited notion of Warhol as painter of soup cans and celebrities.

The films, Factory mementos, were excuses to populate the loft with personalities; thus he could lure incandescent weirdos (as potential actors) to his lair. By staging a spatial artwork—the Factory, a workshop for miscommunication, tableaux vivants, exhibitionism, hysteria—and ensuring that it was well documented by photographers, Warhol proved that his core love was not the two-dimensional art of paper and canvas but the three-or-more-dimensional medium of performance.

In a notebook (undated, probably from the late 1960s, it is lodged in a time capsule at the Warhol Museum), Andy speculated, in broken phrases and images, on how to push art beyond tangible artifacts. One of his notations was “iliminate ART”—his scrawl seems a cross between “eliminate” and “illuminate.” He wanted an art that would dispose of distracting surfaces and thus illuminate the invisible, unfetishized core, and he also wanted to “eliminate ART” as one excretes matter from the body. The Factory eliminated art—crossed art out, but also mechanically evacuated it. In the notebook, he entertained the idea of “GALLERY LIVE PEOPLE”—an exhibition in which people were the art. He realized this dream recurrently, not only at the Factory, but, in 1965, at his first retrospective, in Philadelphia; the museum grew so crowded with spectators that the staff had to take the art off the walls to protect it, leaving the gawkers to stand in for the art.

In June 1963, he moved into a studio on East Eighty-seventh Street, the former Hook and Ladder Company 13 (a firehouse). Here, to help him silkscreen, and to help him realize his ambition of “GALLERY LIVE PEOPLE,” he hired Gerard Malanga, who became his major assistant of the 1960s. Andy paid Gerard $1.25 an hour. He had paid Nathan Gluck $2.50.

The first painting that the new assistant silkscreened was a Silver Liz. However, to the biographer, Andy’s relation with Gerard is nearly as important as the artworks that came from it. Andy called him Gerry-Pie, and Gerard called him Andy-Pie. Gerard was a twenty-year-old Italian boy from the Bronx, an aspiring poet enrolled at Wagner College; he’d studied with poet Daisy Aldan and had won prizes, and was the protégé of husband-and-wife experimental filmmakers Willard Maas and Marie Mencken (a dour-...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Epigraph

- Introduction: Meet Andy Paperbag

- Before

- The Sixties

- After

- Sources

- About the Author

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Andy Warhol by Wayne Koestenbaum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Artist Monographs. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.