eBook - ePub

The Shape of Fear

Horror and the Fin de Siècle Culture of Decadence

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Shape of Fear by Susan Jennifer Navarette in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & English Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Let us begin with that which is without—our physical life.

Walter Pater

1

Rictus Invictus

. . . loathsome sight,

How from the rosy lips of life and love

Flash’d the bare-grinning skeleton of death!

Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Idylls of the King (1859)

Camilla: You, sir, should unmask.

Stranger: Indeed?

Cassilda: Indeed it’s time. We all have laid aside disguise but you.

Stranger: I wear no mask.

Camilla: (Terrified, aside to Cassilda) No mask? No mask!

Robert W. Chambers, fragment from The King in Yellow (n.d.), act 1, scene 2

“What of Art?” she asked.

“It is a malady.”

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891)

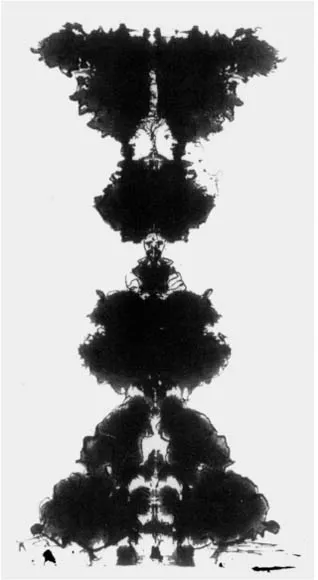

THREE YEARS AFTER THE DEATH of Victor Hugo in 1885, the first exhibition of his graphic works was held at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris. Among the works there assembled were drawings that Hugo had produced during his stay in the Channel Islands, to which he had retreated upon his exile from France in 1851. The nearly twenty years he spent there, first in Jersey and then in Guernsey, proved unusually fertile in an artistic sense, and when he was not absorbed in intense literary work, Hugo devoted himself to the graphic arts. It was during this period that he “discovered” an artistic technique involving and exploiting an inherent degree of chance or risk.1 He began to generate forms and images by folding paper in half and blotting it with ink, or by stamping it with cutouts or objects dipped in ink. He employed the former method, for example, in Tache d’encre sur papier plié et personnages (1853-55) (fig. 1), in which he drew out or encouraged the appearance of the faces and grotesques that he saw lurking within the aleatory shapes. Born of the interaction of imagination and technical ingenuity, and involving, as he himself put it, “all sorts of queer mixtures that eventually render more or less what I have in my eye and above all in my mind,” Hugo’s images are projections from within, their curves, dimensions, and contours roughly approximating the features of subconscious phantoms and the internal landscape they haunt.2

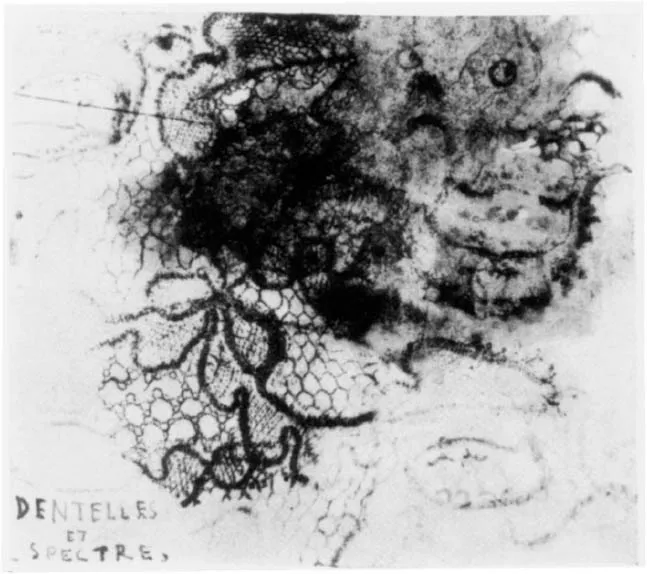

Most of the drawings that Hugo produced during this period are dominated by fluid, amorphous masses from which shadowy patterns, forms, and structures surface, hinting at meanings unsettling and often ominous. The French littérateur Théophile Gautier referred to them as “dark and savage fantasies” imbued with the “chiaroscuro effect of Goya” and “the architectural terror of Piranesi.”3 A unique series of Dentelles (1855-56) contain eerie images created when Hugo dipped a piece of finely patterned lace in ink, pressed it between two leaves of paper, and then enhanced the impression with ink blots. The resultant image would depend on how much of the lace had been treated with ink and on how much pressure had been exerted when the lace was pressed onto the paper. The effect is eerie, for the technique reproduces the highly structured nature of the fabric but also (because the inked pattern is fragmentary) suggests that it is in the process of decomposition.

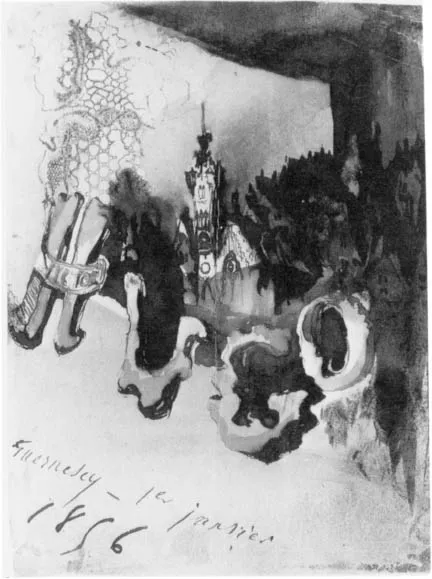

Of this select group of blottesques, three in particular merit close scrutiny: a carte de voeux (fig. 2)—the earliest and best known of the Dentelles—and two of the Dentelles et spectres (frontispiece and fig. 3), so called because in them Hugo conjures up the toothy, grinning skulls that he discovered staring out at him, latent within the filaments of the design. All three pieces are linked by the organicism that Hugo perceived and emphasized within the lacy figurations. The carte de voeux (bearing the handwritten date along the bottom of the card—“1er janvier 1856”—that has allowed scholars to roughly date its companion pieces) is richly evocative. In it, the first letter of Hugo’s last name descends from a fretted image that hovers, wraithlike, in the muted upper half of the card: although so much more substantial than the shadowy entity out of which they materialize, the letters “H-U-G-O” are inextricably tied to an “ancestral” point of origin, however ephemeral or skeletal it may appear, and thus connect the artist himself, by extension, to the reticulated specters of his art.

Figure 1. Victor Hugo, Tache d’encre sur papier plié et personnages (1853-55). Courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

The lace of the Dentelles et spectres, in particular, seems to evoke the physiological qualities of the human body whose grinning skull it discloses. Hugo emphasized and highlighted the amorphousness latent in the fragile, delicately delineated lines that blur and melt in the midst of their own surcharged intricacy, the signature of the fabric’s complexity but also the signifier of its imminent dissolution. Like the human body (which in its healthy state displays a pleasing symmetry but upon its demise reverts to an amorphous chaos, undifferentiated and atomized), lace is characterized by an ornamental design often predicated upon the ordered repetition of symmetrical patternings. It is also, however, an open-work material reminiscent of a skeletal structure from which the flesh has been eaten away (“burnt-out” or “etched,” to use the argot of the lace-makers). The lace of Hugo’s Dentelles et spectres thus functions as a medium revealing underlying structures that (when fleshed out again with haunting images drawn from Hugo’s own reservoir of sublimated horrors) metamorphose into blotted phantoms. The phantoms, turning their gaze upon the viewer, reveal a skeletal rictus with teeth (the French dentelle means “little tooth”) prominently displayed. Viewed in evolutionary terms, lace might be thought of as the Roderick Usher of its species: easily thrilled by external stimuli (the slightest of breezes disturbs it; too strong a light foxes it), easily torn asunder, its complexity quick with dissolution. Its defining quality—its fragile beauty—also poses the greatest threat to its material integrity. It is worth noting that because Hugo utilized the same wisp of lace for the dozen or so Dentelles that he generated, the demise of the fabric signaled the extinction of this particular subspecies of graphic works.4

Working in little—the largest of the Dentelles measures 38 by 13 centimeters, whereas the Dentelles et spectres are even smaller, measuring only 6.5 by 6 centimeters—Hugo brings to light webbed networks of association and meaning in which each mesh draws in all the rest, and thus he compels his viewer to confront the skeletal figures that would otherwise lurk undetected within the larger patterns that constitute the fabric as a whole. He resurrects in this body of work his belief, voiced some twenty years earlier, that “what we call the ugly . . . is a detail of a great whole which eludes us, and which is in harmony, not with man but with all creation.”5 Moreover, he exploits the innately conflictive nature of his medium (lace is, after all, “fretted,” containing both ornamental patterns and cankerous spots in which it is simultaneously made and unmade) and renders explicit what is often ignored (the unstable and therefore unnerving character of a fabric prized for its attenuated beauty). In so doing, Hugo recasts his medium as “the thread”—to invoke the metaphor he introduces in the preface to Cromwell (1827), his disquisition upon “the grotesque”—“that frequently connects what we, following our special whim, call ‘defects’ with what we call ‘beauty’”—a condition synonymous, in Hugo’s view, with “originality” and “genius”:

Figure 2. Victor Hugo, Carte de voeux (1856). Reproduced by courtesy of the Director and University librarian, the John Rylands University Library of Manchester, England

Figure 3. Victor Hugo, Dentelles et spectres (1855-56)

Defects—at all events those which we call by that name—are often the inborn, necessary, inevitable conditions of good qualities.

Scit genius, natale comes qui temperat astrum.

Who ever saw a medal without its reverse? a talent that had not some shadow with its brilliancy, some smoke with its flame? Such a blemish can be only the inseparable consequence of such beauty.6

The lace, suggesting the connection between Hugo’s own genius and his troubled unconscious, also functions as a “medium” in another sense of the word, for it becomes a channel through which an ominous thing intrudes upon the viewer’s field of vision. When we examine lace closely, our eyes stumble across an uneven terrain wherein accretion leads on to black holes of emptiness defined by the edges of grotesques and arabesques. A multitude of tiny abysses mushrooms in the midst of a complex design. M.R. James gave us a way to visualize this very phenomenon in “Mr Humphreys and His Inheritance” (1911), in which, poring over a sheet of paper bearing his original plan for a maze, the eponymous character stumbles across a “hitch” that he had not noticed before: “an ugly black spot about the size of a shilling.” As he stares into the hole—“but how should a hole be there?” he wonders—he is unexpectedly overwhelmed by feelings of hate, then of anxiety, then of horror at the notion that “something might emerge from it” and rise to the surface. And, of course, something does emerge:

Nearer and nearer it came, and it was of a blackish-grey colour with more than one dark hole. It took shape as a face—a human face—a burnt human face: and with the odious writhings of a wasp creeping out of a rotten apple there clambered forth an appearance of a form, waving black arms prepared to clasp the head that was bending over them.7

Hugo’s blottesques in general—and his Dentelles in particular—are similarly transgressive (like the hole in Mr. Humphreys’s plan, which, as we discover, runs down through paper, table, and floor into the “infinite depths” of the abyss), defined by the violation of demarcating borders: those, for example, that separate complexity of design and amorphousness, ornament and decomposition, and, finally, the visible and invisible worlds. The reality that they disclose is deeply imbued with the “sadness” that William James, in The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), detected “at the heart of every merely positivistic, agnostic, or naturalistic scheme of philosophy.” “Let sanguine healthy-mindedness,” he wrote, “do its best with its strange power of living in the moment and ignoring and forgetting, still the evil background is really there to be thought of, and the skull will grin in at the banquet”: “Back of everything is the great spectre of universal death.”8 It is precisely the “evil background” ignored by the sanguine, healthy-minded that becomes the point d’appui for Hugo’s Dentelles, which depict the moment at which the mask begins to slip, revealing the power of the unconscious (just as M.R. James’s story reveals the power of the living past) and a vital source of his creative impulse. What is made suddenly manifest in the Dentelles is not the “unconquerable soul” that seems, for the protagonist of William Ernest Henley’s vigorously optimistic “Invictus” (1888), to be a talisman against the looming “Horror of the shade,” but the grinning bare skeletal truth of things, the always-denied triumph of the horrific: the rictus invictus.

Because the sheer number of drawings displayed there suggested that Hugo’s acuity was as compellingly visual as it was literary, the 1888 exhibition at the Galerie Georges Petit proved enormously important to students of Hugo’s work, prompting a reevalution of what the Belgian symbolist Emile Verhaeren called “l’imagination hugonienne.”9 The exhibition also served as a confirmation of a belief that many of those in attendance had long maintained: that Hugo, “poëte sacré” (the phrase belongs to Auguste Vacquerie, Hugo’s friend and spokesperson) and “dessinateur de génie” (the designation of the painter Benjamin Constant), was quite simply “le Maître.” Stéphane Mallarmé made that role explicit in a letter in which he invited the Provençal poet Théodore Aubanel to reside as his guest in a room that he had carefully decorated with “an old lace thrown over the bed, and simply, together with the portrait of Hugo, the portraits of friends who deserve to be here.”10 The exhibition also revealed that in the Dentelles Hugo had discovered an idiom that rendered the pieces assembled there consonant with two distinct cultural moments—that in which they had been engendered and that in which they were finally disclosed to the gaze of the public. When he identified the “strange originality” and “unlooked for effect” of Hugo’s drawings, which had been born of “the transformation of a blot of ink” and which revealed images “striking, mysterious . . . sometimes sublime, sometimes familiar, always wonderful,” Gautier spoke for viewers such as Edmond de Goncourt, who took particular note of the exposition in his Journal, and Joris-Karl Huysmans, who wrote in praise of “these painted tempests . . . considerably quieter, however, than the hurricane of his sentences” that assail one with an “obsessive fear.”11 All of these aesthetes shared a way of looking at things that was predicated on the notion that the outward and the sensible always bodied forth, however imperfectly, the inward and the ineffable: “a dream of form in days of thought” was how Oscar Wilde expressed this dialectic in The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891).12

Perhaps because he was so fervent an admirer of Hugo’s work, Gautier went to the heart of the master’s otherworldly visions when he alluded to the curious shape that they assumed: “behind the reality he introduces the fantastic like a shadow behind the body, and one never forgets that in this world every figure, beautiful or deformed, is followed by a black spectre like a shadowed page.”13 It was a glimpse of this same crepuscular reality that Nathaniel Hawthorne (a contemporary of Hugo who was similarly intrigued by the notion of an intermediate world of shadows in which things otherwise unseen might be made partially manifest) had hoped to afford his reader when, in a notebook entry of August 14, 1835, he recorded the germ of “a grim, weird story” wherein the “figure of a gay, handsome youth, or young lady” might “all at once, in a natural, unconcerned way, [take] off its face like a mask, and [show] the grinning bare skeletal face beneath.”14 In Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), Thomas Hardy presents his reader with a heroine who, moments before she disfigures the beautiful face that has brought her such woe, presses her hand “to her brow, and [feels] its curve, and the edges of her eye-sockets perceptible under the soft skin,” and, with a prescience symptomatic of what her husband terms “the ache of modernism,” thinks with longing of the time when “that bone would be bare” and when her corporeal frame would thus more truly cohere with her blighted condition.15 The jungle that looks “like a mask—heavy like the closed door of a prison,” with its “air of hidden knowledge, of patient expectation, of unapproachable silence,” whispers to Conrad’s Kurtz of things “of which he had no conception,” but which he approximates by means of a series of heads on stakes—all the faces but one turned in toward his house, and that one (correspondent, presumably, with the rest) “black, dried, sunken, with closed eyelids . . . and with the shrunken dry lips showing a narrow white line of teeth, . . . smiling too, smiling continuously.”16

Similarly populated with apparently robust individuals who nevertheless turn upon the viewer a death’s-head stare, the imaginary worlds of the symbolist artists James Ensor, Félicien Rops, and, in his late “sick” phase, the Viennese artist Anton Romako remind us that Hugo and Hawthorne, as well as their late-nineteenth-century heirs presumptive, were not merely appropriating the image of “the skeleton at the feast” from a momento mori tradition that dates back to antiquity, but taking inspiration from an evolving scientific discourse that increasingly recast the physical world itself as a Melvillean pasteboard mask. Rops’s coquettes romp at masked balls, seducing with fleshless grins (fig. 4), while the subject of Romako’s Portrait of Isabella Reisser (1885) (fig. 5) ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part 1

- Part 2

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index