- 364 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Transport Problem

About this book

Originally published in 1982, this book gives a concise commentary on the development and performance of car ownership prediction procedures and a wide-ranging survey of the modelling techniques associated with forecasting. The book provides a basic appreciation of the key points, whether they are mathematical or otherwise. Throughout the book there is a theme which relates the academic debate surrounding the issue to technical rather than philosophical concepts.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

The Framework

1. The Shortcomings of Some Simple Solutions to the Transport Problem

We are not spending enough on our roads. Few would dispute that. The difficult questions are ‘how much more?’, ‘where first?’ and ‘what is the railways’ part to be in the transport system of the future?’ Finding answers to these questions is the essence of the internal British transport problem. It is tempting to fall for one or other of the easy solutions to the problem. The more respectable are superficially plausible, easily understood and comparatively straightforward to effect quickly. The type of solution developed in this book is complicated and not particularly easy to follow, requiring preliminary investment in what a private firm would call market research and cost analysis. It would mean a radical change in overall transport policy. Speed and simplicity are important practical advantages of the simple solutions. Therefore we must begin by arguing their shortcomings and making the case against them. The general nature of the objection is that they are arbitrary, wild stabs at a solution, possibly preferable only to drifting as we are. If we adopt a simple solution such as we are pressed to do by many disinterested and vested interests, we ought not to be surprised if the country is landed with a road system which on hindsight seems too small or large, a compromise or a showpiece, probably but not inevitably the latter.

Simple Solutions to the Road Problem

These can conveniently be divided into two categories (1) the largely arbitrary (2) those based on international comparisons.

The Largely Arbitrary

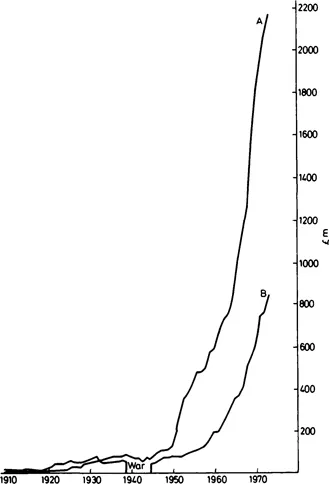

We may mention first the actual amounts spent on the road system in the past by central and local government (see Fig. 1.1). On reflection these amounts seem less than desirable in most years, yet they were intended to be the right amounts to ‘solve’ the road problem in the sense that more would have been too much, less too little in the opinion at the time of the central and local authorities responsible for determining them. The fact was of course that they were governed by (a) short-term considerations and (b) unfortunate theories of public finance.

FIG. 1.1a: Annual expenditure on roads by central and local government

(a) Road expenditure in any given year was affected by the immediate problems of chancellors (and local authorities). One year it was easier to balance a budget, and more was spent on roads. In another constraint would mean roads expenditure was cut. Expenditure was little determined by any long-run conception of the national need for roads.

(b) Roads expenditure got the worst of two schools of economic thought. Between the wars the classical view was generally accepted that budgets should be balanced even in a slump. Although some roadbuilding schemes were promoted to relieve unemployment, illogically on this view, the overwhelming tendency was to place roads well down in the priority list, among dispensable public expenditure items which could wait their turn for prosperity. (Mussolini and Hitler uninhibited by classical economics built more roads.) Since the Second World War roads expenditure has been kept down until recently for the opposite reason. Keynesian economics indicates that public works expenditure is one way of helping to lift an economy out of a slump. Roadbuilding is particularly suitable. Therefore governments postponed a major road programme until the next slump. Because there has been no slump, only slight recessions, roadbuilding has never caught up on what it has lost during the long postwar boom. Recently it has become plain that it is foolish to delay a road-building programme for a slump which Government policy should be able to prevent ever happening.2 Consequently expenditure on the roads has increased markedly. This is the problem: the Government knows that expenditure is moving in the right direction, but it does not know where the upward movement should level off – at £200m. a year, £250m., £300m.? Past policy and practice has nothing to tell us what the level of expenditure should be, once it is agreed that this level is to be governed by long-term considerations.

The most popular simple solution moves on a step. It would relate what is spent to what road-users pay in taxation. The argument is that road-users are overcharged, and that they have the right to have spent on roads what they pay for their use. When Lloyd George first taxed motorists in 1909 he established the now notorious Road Fund. The new taxes were to be paid into it and should be used only for roads. That was his promise. The promise was broken. The fund was raided to help pay for the First World War; it was raided by Winston Churchill in 1926 and 1927, and by Neville Chamberlain in 1935 and 1936, for general purposes of Government expenditure. The fund was formally abolished in 1955. ‘What with raids and one thing and another,’ said Mr Henry Brooke, then Financial Secretary to the Treasury, ‘the Road Fund has had a chequered career. It was ... fed by hypothecated revenues from motor taxation up to 1937 but since 1937 no hypothecated revenues have been paid into the fund. Instead the fund has been fed directly from the Exchequer. In other words the Road Fund was originally like a tank that was fed by a particular stream. Now for the last eighteen years that has ceased to be so and the Road Fund is a tank connected with the main, and the money flows through the tank from the Exchequer and is used for road expenditure.’3 Abolition did not remove but rather sharpened the sense of grievance felt by many motorists and the motorists’ associations. A glance at fig. 1.1 shows that apparently they have not been getting their money’s worth since 1932. The surplus of taxation over expenditure has grown rapidly since 1949.

Alleged overcharging is made up of two sums: (a) arrears from past years and (b) the present annual surplus of taxation over expenditure. Some argue road-users have a moral right to (a) and (b). Some would be satisified with (b). This simple solution is therefore that roads expenditure should be increased by (b), or by (a) plus (b). We must disentangle the issues.

Road users have no right to these sums. Like all indirect taxes all or any part of them can be regarded as contributions to the general expenses of government. Parliament has the right to use taxes for any purpose it pleases. If it is argued Lloyd George promised this taxation would be used only for roads, the proper rejoinder is he had no right to try to bind his successors in this way. Churchill gave two valid though, as it happened, mutually exclusive reasons for ‘raiding the Road Fund’ in 1926.4 The first was that all expenditure incurred on the sum ‘raided’ would cover the extra expense on police for which the motorist was responsible. The second was that he proposed to regard the part of taxation kept in the Road Fund as payment for the use of roads, and the part he was transferring as the proceeds of a tax on luxury. At different times British parliaments have regarded varying proportions of this taxation as a contribution to the war effort, a general purchase tax, a tax on luxuries, a method of redistributing income, of restricting the use of imported oil and simply as a means of raising money when it could not be raised in some other way. Parliament being sovereign there is nothing more to be said about the supposed right of the British motorist to (a), or (a) plus (b).

Nevertheless there are good reasons for returning to Lloyd George. Although Parliament is the law unto itself and for us all, it would be more sensible if as a general rule motor taxation were regarded as a price paid for the use of roads.5 Indeed this is a prerequisite of an economic solution of the road problem. Some form of accounts must be drawn up relating what is spent on the roads to what is paid for the use of the roads. In so far as taxation is payment for the use of roads, it should be separate from taxation of vehicles, fuel, etc. levied for any other purpose. (We will consider how we should work out the details of such a pricing system in Chapter 10.) If we do use taxation as a charge for the roads, there is a strong case for relating it to the costs of providing the roads. It follows we should rid our tax system of taxes which bear especially hard on motorists compared with other sections of the population and distort the allocation of resources. (By contrast the rationale behind special taxation of tobacco, entertainments, betting, is clear enough whether one agrees with it or not. But why tax someone who spends money on using the roads more pro rata than someone who buys a refrigerator?) This does not imply that all taxes levied on road-users must be spent on roads, but that if it is decided there should be a purchase tax or luxury tax on certain commodities of which travel is one, motorists should not be taxed differently from anyone else in this respect. This is the case for keeping these other taxes which are not a charge for using roads formally separate, their purpose explicit, and preserving the bookkeeping convention of a road fund which publishes accounts similar, let us say, to those of a nationalised industry.

If we were to ignore these difficulties and accept that taxation of road-users should be and always should have been equal to expenditure on behalf of road-users, there are other reasons why the actual figures shown in fig. 1.1 are worthless. First the basis of the figures given for expenditure, those usually quoted, is inadequate. It includes such items as maintenance, improvement and new construction of roads by the Ministry of Transport and local authorities; cleansing, watering and snow clearing; the provision and maintenance of police vehicles used on traffic duty; some research and traffic surveys; trunk road lighting; salaries and establishment charges of surveyors. It does not include other items which have as much reason to be in. A figure can be put to some of these, for example the expenses of local authorities in registering vehicles and collecting duties (£2.7m. in 1957-8) and expenditure on street lighting (£23.8m. in 1958-9.) Other items are not separated out in the public accounts: for example police costs, other than for police vehicles, in respect of traffic; the administrative costs of the road system, which are borne on the Ministry of Transport vote or by the general expenditure of local authorities: that part of the Road Research Laboratory’s costs which is met on the vote of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. A conservative estimate of these three only, might be about £70m. a year. There are certainly other items that should be included. Our present position is rather as would be obtained if a private firm should casually omit one item in three in working out the costs. In case anyone should be interested, counting all these in is not likely to eliminate the surplus of taxation over expenditure unless two controversial items are brought in: the cost of road accidents (estimated at roughly £220m. in 1959) and the cost of congestion, a cost imposed by road-users on each other (perhaps £630m. in 1961). If these are admitted or an equally controversial rent is charged for the use of land embodied in roads, ‘expenditure’ would exceed tax receipts. (We will examine the case for and against considering these as costs to be met by road-users in Chapter 9.)

The argument does not all go one way. The figure given for taxation is dubious for reasons other than those given earlier. There is a false antithesis: taxation of motorists against expenditure on behalf of road-users. Not all road-users are motorists. In fact some road expenditure is financed out of rates (£97m. in 1960-61). And most of the accident and congestion costs are not Government expenditure. Some expansionists conclude from this that the proper contrast is between motor taxation and that proportion of expenditure not financed out of rates; that is, central Government expenditure which given the expenditure figures of fig. 1.1, increases the extent of ‘overcharging’ considerably. (This is usually put as the proposition that only 15 per cent of what motorists pay is returned to them in expenditure.)6 Others would argue that the wrong proportion of road expenditure is financed out of rates and that some different proportion should be used to work out the extent of ‘overcharging’.

The fact remains that there are many views which can be taken on what receipts should be matched with what expenditure. The surplus shown in fig. 1.1 is based on one definition of relevant receipts and relevant expenditure. And, what is very important, the right definitions a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction to the Second Edition

- PART I THE FRAMEWORK

- PART II THE RAIL PROBLEM

- PART 3 THE ROAD PROBLEM

- PART IV THE TRANSPORT PROBLEM

- APPENDICES

- Notes and References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Transport Problem by C. D. Foster,Christopher D. Foster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & City Planning & Urban Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.