![]()

1. Tribute to John Alexander

Simon Stoddart

The editors of this volume would like to take the opportunity to remember, even if briefly, the contribution of the late Dr. John Alexander (27 January 1922 – 16 August 2010) to the Iron Age archaeology of the Balkans, and more broadly in Europe as a whole. He taught the Iron Age in Cambridge from 1974 until his retirement in 1984 and was the lecturer who introduced this editor to the subject, and was warmly generous in his support with his gifts of time, ideas, books and photographic slides. Nevertheless, although his role in local (Evans et al. 2008; Legge et al. 2011), national and African (particularly Sudanese) archaeology (e.g Renfrew 2004; Shinnie 2004; Wahida and Wahida 2004b) has been well recognised, the attempt to publish a conference held in Oxford (including Stoddart unpublished) on his contribution to the Iron Age never materialised. The Azania festschrift (Wahida and Wahida 2004a; 2004b; Shinnie 2004) draws attention to his contribution within the European Iron Age, but there has never, to our knowledge, been a specific reference to his contribution towards the first millennium bc in Europe. This short dedication meekly meets that requirement.

His central contribution to the study of the Balkans in the Iron Age was, appropriately for this volume, his book Jugoslavia before the Roman conquest in the Thames and Hudson People and Places Series (Alexander 1972b) and a significant earlier article for Antiquity on the Balkans’ geopolitical position in the European Iron Age (Alexander 1962), as well as broader syntheses (Alexander 1980a). In many important respects, he was a figure who encouraged dialogue between South East European and British Archaeology by undertaking his doctoral dissertation on this region too little known in Britain at the time. The People and Places volume was reviewed by Alan McPherron (1973) as an important, albeit traditionally grounded, piece of scholarship that provided the best assessment of the Iron Age of the Balkans in English at the time. It is true that much of his work focused on the development of the leitmotifs of material culture, most notably the pin (Alexander 1964) and the fibula (Alexander 1965; 1973a; 1973b; Alexander & Hopkin 1982), but he did move purposefully on from these foundations to look at key themes. In this respect he was ahead of his time, or perhaps affected by the presence of David Clarke writing on similar themes (Clarke 1987), a transitional figure who was comfortable with the details of material culture, but also interested in new interpretative frameworks. For some themes, such as urbanism (Alexander 1972a), he contributed to the collective studies of others. In other themes, he very much benefited from forging the comparison between the African and European evidence, looking at the parallel pathways in Africa and Europe for themes as diverse as iron (Alexander 1980b; 1981; 1983), salt production (Alexander 1975; 1982; 1985), religion (Alexander 1979) and the dynamic frontier (Alexander 1977). Another prominent theme in his teaching was to re-assess the traditional categories of Hallstatt and La Tène in terms of their socio-political implications, and ultimately argue that such categories should be replaced by the understanding of cross-cutting processes articulated by absolute chronologies. On the other hand, it is perhaps indicative in terms of this present edited volume, that he is not cited outside this preface, because Balkan archaeologists have made so many strides in terms of data collection as well as interpretation over the last forty years, and although he laid some foundations in terms of material culture, identity was not a theme prominent in his vocabulary. As many authors point out in this volume, identity is more emphatically a rhetoric of this current age rather than of his, and the impact of these modern concerns is more readily seen in current studies of the first millennium BC.

![]()

2. Introduction: the Challenge of Iron Age Identity

Simon Stoddart and Cătălin Nicolae Popa

Issues of identity and ethnicity have gained much in popularity over the last two decades. A considerable number of studies have been dedicated to investigating how small and large scale solidarities were constructed and maintained and how they were reflected at the level of the individual. Archaeology has been dealing with identity, and especially with ethnicity issues, as far back as Kossinna’s time, but modern approaches are radically different, emphasising dynamic and fluid construction.

The archaeology of the Iron Age strongly reflects such a situation. The appearance of written sources in this technological horizon has led researchers to associate the features they excavate with populations named by Greek or Latin writers. Under the influence of anthropological studies, a number of scholars coming from the Anglo-Saxon school have identified biases and dangers inherent in such an approach to the material record. This has led many scholars to write forcefully against Iron Age ethnic constructions, such as the Celts. At the other extreme, some archaeological traditions have had their entire structure built around notions of ethnicity, around the relationships existing between large groups of people conceived together as forming unitary ethnic units.

These approaches constantly need to be debated, and this volume, broadly based on the 2011 Cambridge conference, presents debates which have had greater problems penetrating a very fertile region for Iron Age studies, the geographical region of south east Europe. In this part of the continent, the mainstream view of ethnicity remained, until recently, that of a solid, clearly defined structure, easily identifiable in the archaeological record and dangerously played out in the present. The Iron Age of this region has, until late, been populated with numerous ethnic groups with which specific material culture forms have been associated, and which modern politicians and military leaders have exploited. The divorce between studies of south east Europe, at one limit of Europe, and Britain, at the other, has had a profoundly negative impact on Iron Age studies, particularly when it comes to how ethnicity is perceived and conceptualised, and has had, for at least the second time in the twentieth century, deleterious effects on modern politics. In the opinion of the editors, these radically different views (and their political consequences) emerged from a lack of dialogue as well as interrogation of the available data. This volume attempts to present the diversity of this dialogue, and its theoretical repercussions, undertaken initially in the harmonious precincts of Magdalene College, Cambridge, but now transferred, at least in part, into printed format.

The conference forms part of a wider series where a key theme in the “long” Iron Age is combined an appropriate region in a comparative European framework. The framework was conceived by one editor (Stoddart) and has already seen the full cycle from conference to publication in a theme related to the current volume of ethnicity bedded in Mediterranean landscape (Cifani et al. 2012). The current region and theme was selected by the second editor (Popa) who brought the fresh stimulus of the early career scholar, supported by his research focus on identity, drawn principally through burial in south east Europe.

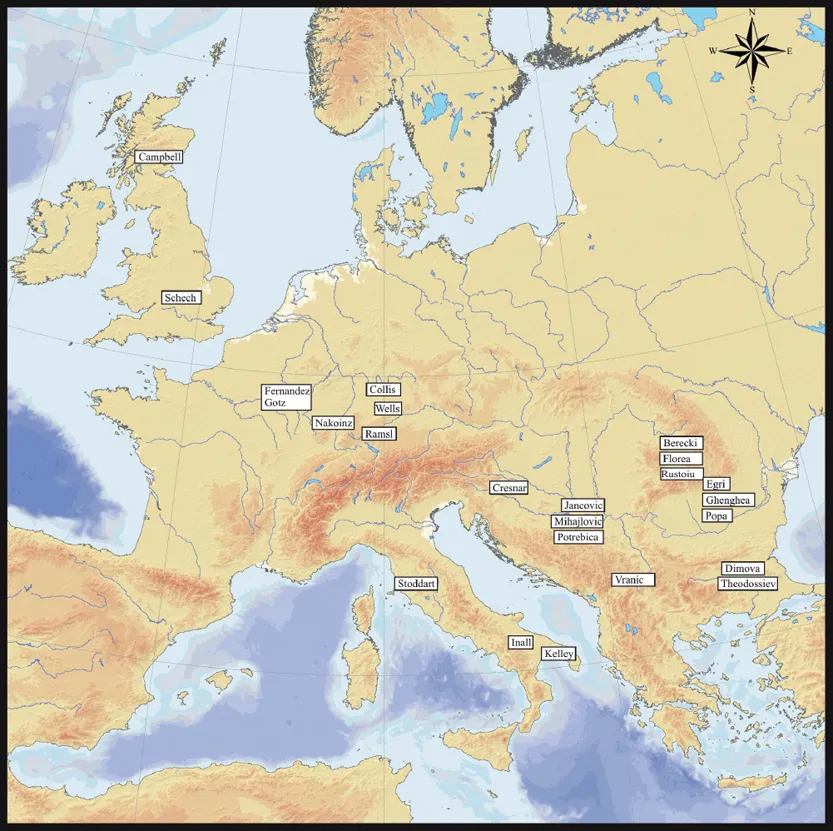

The volume contains twenty four contributions which have been arranged alphabetically by first author within five sections. The first most populous section is devoted to the core geographical area (Fig. 2.1) of south east Europe. This has contributions from the modern countries of Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania, Serbia and Slovenia that also make reference to Albania and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. The following three sections allow comparison with regions further to the west and the south west. A section where three papers investigate central and western Europe is followed by two papers in a smaller section on the British Isles. The regional theme is completed with a section including three papers on the Italian peninsula, although one links back into modern Croatia. The volume concludes with four papers which provide more synthetic statements that cut across geographical boundaries. The final of these contributions by the editors brings together some of the key themes of the volume.

The overall analysis of the lessons of the volume is deliberately left to the final chapter, but it is worth outlining some of the cross cutting approaches ahead of the papers themselves. In line with current trends of the study of identity, most of the approaches are substantially qualitative in their analysis. However, it is worth noting the prominence of quantitative analysis of material culture in six of the 24 papers (Dimova, Inall, Kelley, Nakoinz, Popa and Foulds) and this prominence necessarily raises one issue about the level to which identity can be measured explicitly, an issue that a number of the same papers deliberate. The remaining papers all focus on the more qualitative assessment of identity. For some, it is the heavy hand of the recent present that has all too readily defined the engagement with the past, a perspective that is strongly argued by Babic, Collis, Ghenghea, Mihajlovic, Popa, Stoddart, Vranic and Wells, amongst others. For other authors, there is a more confident identification of identity in material culture (Berecki and the Celts; Potrebica/Dizdar for various identities; Rustiou for mobile identities; Theodossiev through literary sources). For some, multiplicity, hybridity and ultimately fuzziness are dominant themes (Campbell, Cresnar/Mlekuž, Stoddart and Wells). Issues of biology are largely ignored, although this has proved impossible to ignore completely in the case of Etruria for reasons which lack the dangerous historicity of areas further north. Material culture is generally of the portable kind, but some papers do introduce issues of landscape (notably Cresnar/Mlekuž and Fernandez-Gotz), in common with other recent attempts in the same direction (Stoddart and Neil 2012). The wide array of approaches to identity reflects the continuing debate on how to integrate material culture, protohistoric evidence (largely classical authors looking in on first millennium BC societies) and the impact of recent nationalistic agendas. Fortunately, there is at least now relative agreement about the last of these, and one success of the conference was to bring together for harmonious debate scholars from countries who had so recently employed similar agendas in the prosecution of war and discord on European soil.

In more detail, in order of appearance within the volumes, this is succinctly what each article offers. The volume opens with a brief tribute to John Alexander who was one of the first scholars (together with Roy Hodson) to set up the engagement of Britain with the Iron Age of south east Europe. The thirteen papers from south east Europe demonstrate the diversity of approach. Sándor Berecki emphasises the multiplicity of elements within the characterisation of Celticity, and indeed considers multiplicity to be an underlying character of Celtic identity in Transylvania. Matija Črešnar and Dimitrij Mlekuž underline the importance of situating ambiguous identities in the landscape of Slovenia, and bring fresh archaeological evidence and methodologies in support of their case. Bela Dimova examines principally one dimension of identity, namely gender, engaging modern theory with the rich Thracian evidence at her disposal, whilst acknowledging multi-scalar relationships. Mariana Egri focuses on the widely acknowledged performance of identity in the act of drinking during the first millennium BC, successfully engaging with the tension provided by textual commentaries on non-Classical practice in the region of ancient Romania. Gelu Florea investigates the identity of place, by examining in detail one key politically orchestrated site in Transylvania, drawing together old and recent evidence. Alexandra Ghenghea takes a strongly historiographical approach, showing how forcefully bounded identities, tinged with Romanian nationalism, emerge from pre-contemporary scholarship. Some scholars suggest that ethnicity is more likely to occur in competitive political conditions, but Marko Janković questions the presence of ethnicity even in a context, the Roman province of Moesia Superior, where such conditions might be intimated to exist, and suggests that such a term should be replaced by the cross-cutting identity of status. Vladimir Mihajlović rightly criticises the retrojection of ethnic terms in the central Balkans back onto prehistory, running against the stream of time and political development. Catalin Popa processes apparently unpromising funerary data from Romania into a coherent understanding of identity that deconstructs the standard accounts of Dacians. Hrvoje Potrebica and Marko Dizdar combine their temporal specialisations to look at the long-term changes in identity over the full period of the Iron Age of the Southern Pannonian plain, working with concepts old and new. Aurel Rustoiu tackles the key issue of mobility of populations and retention of identity in the dynamic world of the late Iron Age of the Carpathians. Nikola Theodossiev synthesises the history of Thrace in the light of broader inter-regional trends. Finally, in this section, Ivan Vranic takes a post-colonial approach to Hellenisation, that overtly acknowledges the enduring impact of the political present, centred on differential interpretation of regions such as Macedonia.

The next five papers transport the reader west. The first by Manuel Fernández-Götz places ritual at the centre of imagined communities, taking as his evidence new data from the Titelberg and similar sites in north western Europe. Oliver Nakoinz’s work concentrates on the mathematically modelled definition of identities in south west Germany, differentiating between different outcomes on quantitative grounds, whilst attempting to link this to qualitatively based theory. Peter Ramsl dissects some examples of graves from the peri-Alpine area which he proposes permit a dis-assembling of compounded identities. Louisa Campbell interprets the presence of Roman material culture beyond the political frontier of the Roman world in northern Britain in terms of locally negotiated identities. Elizabeth Foulds looks at how glass adornment can inform on the multiple identities of dress in Iron Age Britain.

The next small section moves into the Italian peninsula where, if the written sources are to be believed, firmly defined identities might have been expected to be present in the Iron Age. Yvonne Inall shows the fluidity of martial identity interpreted through a new typology of spearheads from southern Italy. Olivia Kelley illustrates the multiplicity of identities read from the burials of Peucetia in southern Italy. Simon Stoddart presents the contrast between the fluid, multiscaled identities of the Etruscans and the unitary identity sought by ancient writers and early scholars, and seeks to stress the multivalency of Etruscan identity by looking at the discovery of multiple exotic examples of material culture as well as local hybridity in the Croatian site of Nesactium.

The volume closes with synthesis. Staša Babić shows how the interpretations of past identities have been historically deeply seated in the present within her own native Serbia. John Collis provides an update of his identity of Celticity contrasted with the identities of others, expressed in his own personal, inimitable style. Peter Wells investigates some of the key identities drawn from the ancient authors in terms of modern interpretation and illustrative examples from central Europe. Finally the editors draw together the key themes of the volume.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The original conference of 23–25, September 2011 was supported by the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, the ACE Foundation and the Ironmongers Livery Company. The record of the original conference has been archived on the internet: http://www3.arch.cam.ac.uk/iron_age_conference_2011/. The publication has been enabled by the kind support of Brewin Dolphin Investment Managers who characteristically invested with good judgement in emerging intellectual markets. David Redhouse supplied the map in this introductory chapter. The peer review was kindly undertaken by a range of scholars whose importance and investment of time will be acknowledged by sending them a copy of the finished product. The main editing was undertaken by Simon Stoddart, ably supported by Catalin Popa. The index was constructed by Catalin Popa and Simon Stoddart. The front cover was conceived by Barbara Hausmair. Formatting was undertaken by Mike Bishop and the Oxbow production was overseen by Clare Litt.

Figure 2.1. The distribution of the articles in the volume within Europe.

![]()

Perspectives from South East Europe

![]()

3. The Coexistence and Interference of the Late Iron Age Transylvanian Communities

Sándor Berecki

KEYWORDS: CARPATHIAN BASIN, SPIRITUAL INTERFERENCES, MATERIAL CULTURE, LATE IRON AGE

Every society is given a special character by its embedded ‘foreign’ elements. In its process of expansion and colonisation (Szabó 1994: 40), Celtic society proved to be widely receptive to the influences of the indigenous populations of conquered territories. Celtic communities had contact with several populations in a period starting in the last third of the fourth century BC (Berecki 2008a: 47–65), as they expanded towards the eastern part of the Carpathian Basin. These local groups directly or indirectly influenced the spiritual and material culture of the newcomers. On the other hand, the Celts promoted a material culture adopted by the communities of the region, coming to create the heterogeneity of the Transylvanian ‘Celtic’ Iron Age. This paper emphasises some features of the identity of these communities, which are interpreted as derived from the coexistence and interference of the Late Iron Age Transylvanian populations and their neighbours.

In the southern regions of the Carpathian Basin, reciprocal interferences of the fourth century BC resulted in the admixture of Illyrian, Pannonian, Thracian and Celtic...