![]()

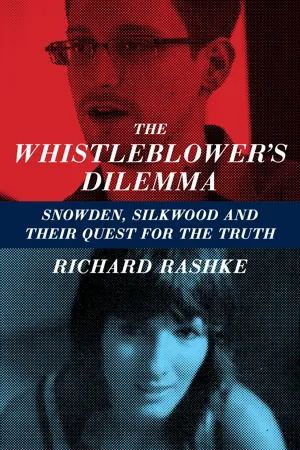

The Whistleblower’s Dilemma

In June 2013, Edward Snowden shoved himself and other whistleblowers like Karen Silkwood into the spotlight when he leaked top-secret National Security Agency (NSA) documents. In so doing, he reminded the nation that whistleblowing is both a First Amendment right, albeit controversial, and a necessity to keep government and commerce honest. Snowden’s actions provoked a series of questions ranging from nettlesome to troublesome:

Are whistleblowers heroes or traitors?

Are whistleblowers snitches or saviors?

Do they have a legal, moral, or ethical obligation to blow the whistle?

Do they do more damage than good for the nation?

What personal price do they pay?

Is it worth it?

Most of the hundreds, if not thousands, of whistleblowers never earn ink on the front pages of national newspapers or their online counterparts. Most of the whistleblowers who make headlines do so because they have exposed the secrets of powerful corporations and government agencies with seemingly unlimited resources to hound, scare, silence, and break their critics financially, physically, mentally, and spiritually. Whistleblowers who leak classified government secrets force the nation to question the legality or criminality of their controversial activity. These whistleblowers also leave the government with little choice but to charge, try, convict, and sentence them under the Espionage Act of 1917—as the U.S. Department of Justice did with Wiki leaker Chelsea (formerly Bradley) Manning and threatens to do with Edward Snowden, if it can ever extradite him to the United States to face a judge.

A potential whistleblower who discovers wrongdoing is, more often than not, forced to grapple with a life-altering or life-shattering dilemma. What to do?

Look the other way. “It’s none of my business.”

Rationalize the problem. “It goes on everywhere, so why should I stick my neck out?”

Pass the buck. “It’s somebody else’s problem, not mine.”

Be pragmatic. “Nothing will change anyway.”

Protect self and family. “It’s too risky.”

Get rich. “Doesn’t the government pay for information on waste and fraud?”

Blow the whistle. “It’s my duty.”

Researchers such as sociologists Joyce Rothschild and Terance D. Miethe, who have conducted an extensive survey of whistleblowers and written thoughtful articles on the whistleblowing phenomenon, have provided a context to evaluate and understand both Edward Snowden and Karen Silkwood. One of their important findings is that, unlike Snowden and Silkwood, at least half of those who observe wrongdoing in the workplace remain silent. They fear retaliation and believe that blowing the whistle wouldn’t do any good. Why take the risk?

Rothschild, Miethe, and other researchers have also discovered striking similarities among whistleblowers who, like Snowden and Silkwood, challenged organizations rather than individuals.

Most or a vast majority of whistleblowers were naïve before they reported wrongdoing. They didn’t understand the risks or foresee the consequences. They reported the wrongdoing internally rather than to the media, which they considered a last resort. And they were motivated to blow the whistle by pride in their work and/or by “personally held values.”

Most or a vast majority of whistleblowers saw their job performance ratings decline, experienced an increase in the monitoring of their work and phone calls, and were eventually fired or forced to resign. Fellow workers, warned to avoid contact with them, shunned them, making them pariahs in the workplace. Most experienced some form of retaliation by their employer that resulted in severe depression or anxiety, deteriorating physical health, severe financial loss, and stressed family relations. The retaliation against them was greater when the wrongdoing was “systemic”—an essential part of the culture and modus operandi of the organization.

Most or a vast majority of whistleblowers felt that the stress, insecurity, loss of sleep, feelings of isolation and powerlessness, anger, and paranoia damaged their physical, spiritual, and mental health for up to five years. Furthermore, they observed no significant positive change in the organization they blew the whistle on, and they watched the wrongdoer go unpunished.

Of course, whistleblowers can always file a harassment lawsuit against their employer, but the chances of winning are slim. As a complainant, the whistleblower would have to prove that the alleged intimidation and harassment was an unwarranted and deliberate punishment for blowing the whistle. Such cause and effect is difficult to establish in a court of law. Furthermore, the whistleblower would have to fell a Goliath armed with a fat wallet and backed by an army of high-priced attorneys. Already financially stressed, how long could a lone David hold out?

Here lies the whistleblower’s dilemma. Given the frightening and predictable consequences, why would whistleblowers like Snowden and Silkwood want to expose illegal activity, corruption, criminal negligence, or fraud?

![]()

2

Disillusioned

Edward Snowden

Edward Snowden was a self-taught computer maverick who dropped out of high school at the age of sixteen. Later, professional colleagues called him a genius. He chose to leak his classified NSA documents to Glenn Greenwald, another maverick. Trained as a constitutional lawyer at New York University, Greenwald began his career as a litigation attorney. He went on to become an award-winning author, journalist, and columnist, and an expatriate who worked out of a remote mountain home overlooking Rio de Janeiro.

Greenwald’s writings explain why Snowden chose him: his 2001 bestseller, With Liberty and Justice for Some, examines the double standard of the U.S. criminal-justice system—one for the powerless and one for high-level government officials. The book made him the darling of privacy-rights activists and the champion of “justice for all.” The “all” included President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney, who approved, according to Greenwald, illegal and unconstitutional invasions of the privacy of American citizens in Trailblazer and StellarWind, NSA’s secret bulk-data-collection operations.

“By ordering illegal eavesdropping,” Greenwald argued, “the president had committed crimes and should be held accountable for them.”

In sum, Glenn Greenwald had a set of sharp teeth and loved to nip at the heels of bureaucrats, politicians, and high government officials. When Edward Snowden first contacted him in December 2012, Greenwald was skeptical. With his international reputation at stake, he was not about to be conned by a self-proclaimed computer professional who said he worked for the U.S. intelligence community. Greenwald approached Snowden with a great deal of caution and a prudent dash of journalistic skepticism. When he finally met Snowden face-to-face seven months after Snowden had first contacted him, Greenwald grilled the former CIA and NSA systems analyst and hacker for five uninterrupted hours. Like a wily prosecutor, he laid traps designed to catch Snowden in lies and inconsistencies, or ducking behind vague answers. After the marathon interview, Greenwald concluded: “Snowden was highly intelligent and rational, and his thought processes methodical. His answers were crisp, clear, and cogent. In virtually every case, they were directly responsive to what I had asked, thoughtful, and deliberate. There were no strange detours or wildly improbable stories of the type that are the hallmark of emotionally unstable people or those suffering from psychological afflictions. His stability and focus instilled confidence. … I was convinced beyond any doubt that all of Snowden’s claims were authentic and his motives were considered and genuine.”

Snowden’s subsequent online and media interviews reveal little if anything to contradict Greenwald’s observations and conclusions. They show him to be flawlessly articulate. His words flow in an unhurried, gentle manner. Sometimes he’s even witty. He never seems to stumble. Or fail to complete a sentence. Or pause in search of the right word. Or sound overly boastful. To the contrary, he projects the image of a calm, confident, and sincere young man with nothing to hide. The only time he appeared nervous was when he first identified himself to the world as Edward Joseph Snowden, the person who had leaked highly classified NSA documents to the media.

For a kid without a high school diploma or GED certificate, Snowden’s career path borders on stunning. The following account shows that Snowden was far from the low-level computer geek that government damage controllers tried to make him out to be.

“Ed” Snowden grew up inside the dense Washington-Baltimore corridor, a fifteen-minute drive from the headquarters of the NSA at Fort Meade, Maryland. The National Security Agency—or “No Such Agency” as the NSA is playfully called—occupied an eleven-story steel and glass cube that sits on a 350-acre campus guarded by its own police force and employing more than 30,000 people. Young Snowden was so undistinguished that former classmates and teachers barely remember him. Nor did he stand out as a Boy Scout. If he was remembered at all, it was as a kid obsessed with video games. Later in life he would credit video games with helping to shape his worldview. “The protagonist,” he explained, “is often an ordinary person who finds himself faced with grave injustices from powerful forces and has the choice ...