eBook - ePub

Anne Sexton

A Self-Portrait in Letters

- 433 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

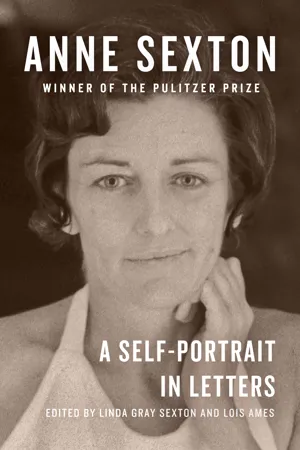

Anne Sexton

A Self-Portrait in Letters

About this book

A revealing collection of letters from Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Anne Sexton

While confessional poet Anne Sexton included details of her life and battle with mental illness in her published work, her letters to family, friends, and fellow poets provide an even more intimate glimpse into her private world. Selected from thousands of letters and edited by Linda Gray Sexton, the poet's daughter, and Lois Ames, one of her closest friends, this collection exposes Sexton's inner life from her boarding school days through her years of growing fame and ultimately to the months leading up to her suicide.

Correspondence with writers like W. D. Snodgrass, Robert Lowell, and May Swenson reveals Sexton's growing confidence in her identity as a poet as she discusses her craft, publications, and teaching appointments. Her private letters chart her marriage to Alfred "Kayo" Sexton, from the giddy excitement following their elopement to their eventual divorce; her grief over the death of her parents; her great love for her daughters balanced with her frustration with the endless tasks of being a housewife; and her persistent struggle with depression. Going beyond the angst and neuroses of her poetry, these letters portray the full complexities of the woman behind the art: passionate, anguished, ambitious, and yearning for connection.

While confessional poet Anne Sexton included details of her life and battle with mental illness in her published work, her letters to family, friends, and fellow poets provide an even more intimate glimpse into her private world. Selected from thousands of letters and edited by Linda Gray Sexton, the poet's daughter, and Lois Ames, one of her closest friends, this collection exposes Sexton's inner life from her boarding school days through her years of growing fame and ultimately to the months leading up to her suicide.

Correspondence with writers like W. D. Snodgrass, Robert Lowell, and May Swenson reveals Sexton's growing confidence in her identity as a poet as she discusses her craft, publications, and teaching appointments. Her private letters chart her marriage to Alfred "Kayo" Sexton, from the giddy excitement following their elopement to their eventual divorce; her grief over the death of her parents; her great love for her daughters balanced with her frustration with the endless tasks of being a housewife; and her persistent struggle with depression. Going beyond the angst and neuroses of her poetry, these letters portray the full complexities of the woman behind the art: passionate, anguished, ambitious, and yearning for connection.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter I

The Business of Words

December 1957–September 1959

“The great theme is not Romeo and Juliet … The great theme we all share is that of becoming ourselves, of overcoming our father and mother, of assuming our identities somehow.”

—from Anne’s early introduction for “The Double Image”

[TB], used during readings of her poetry

In December 1956, Anne had seen the program “How to Write a Sonnet” on Educational Television. Curiosity overcame her fears of rejection and she telephoned her mother, the only person she knew who had written poetry, to ask “What is an image?” Shortly after Christmas she showed her toughest critic her first sonnet of the decade.

Dr. Sidney Martin also encouraged Anne. He recognized that her therapy progressed as she began to discover and appreciate her talents. As if to compensate for all her earlier years of scholastic laziness, she worked hard to learn about both poetic form and herself. She found that emotions she couldn’t deal with in therapy appeared increasingly in her poetry worksheets. Spending hours listening to the tape recordings of her psychiatric sessions, and days rewriting her worksheets, she slowly pulled poetry from the dark core of her sickness.

In September of 1957, believing that she needed a teacher, Anne enrolled in a poetry seminar taught by the poet John Holmes at the Boston Center for Adult Education. Here she met Maxine Kumin, who would be her staunch friend and constant companion in poetry for the next seventeen years. Maxine, a Radcliffe graduate, possessed a technical expertise and, an analytic detachment that balanced Anne’s mercurial brilliance.

As the years went by, Anne and Maxine often communicated daily, by letter if separated by oceans, otherwise by telephone. They supervised each other’s poetry and prose, “workshopping” line by line for hours. They discussed husbands, friends, loves, and enemies; they worried and exulted over their children and their publications, borrowed each other’s clothes, and criticized each other’s readings.

If anyone else viewed Anne’s writing as therapy or a hobby, she did not. Very quickly she established a working routine in a corner of the already crowded dining room. Piled high with worksheets and books, her desk constantly overflowed onto the dining room table; she wrote in every spare minute she could steal from childtending and housewifely duties. To make extra money for baby sitters, she began to sell Beauty Counselor cosmetics door-to-door.

By Christmas Day 1957, Anne could present her mother with a sheaf of poems she had written and rewritten over the previous year. She began publishing on a modest scale in The Herald Tribune, The Fiddlehead, and The Compass Review. On July 28, 1958, “The Reading” appeared in the Christian Science Monitor.

THE READING

This poet could speak,

There was no doubt about it.

The top professor nodded

To the next professor and he

Agreed with the other teacher,

Who wasn’t exactly a professor at all.

There were plenty of poets,

Delaying their briefcase

To touch these honored words.

They envied his reading

And the ones with books

Approved and smiled

At the lesser poets who

Moved unsurely, but knew,

Of course, what they heard

Was a notable thing.

This is the manner of charm:

After the clapping they bundled out,

Not testing their fingers

On his climate of rhymes.

Not thinking how sound crumbles,

That even honor can happen too long.

A poet of note had read,

Had read them his smiles

And spilled what was left

On the stage.

All of them nodded,

Tasting this fame

And forgot how the poems said nothing,

Remembering just—

We heard him,

That famous name.

During the next twelve months she submitted poems to a number of the more prestigious literary magazines and by the fall had received several more acceptances: The Hudson Review had agreed to publish “The Double Image” [TB], “Elizabeth Gone” [TB], and “You, Dr. Martin” [TB], and The New Yorker had taken “The Road Back” [TB]. By early 1959 not one finished poem remained unsold. That April, Houghton Mifflin signed the contract for her first book, To Bedlam and Part Way Back. And in 1960 Anne wrote “poet” under the occupation column on her part of the joint income tax statement. Even her children began reporting to teachers and friends that a mother was “someone who types all day.”

But her success with her poetry could not block out personal crises. Anne tried to care adequately for Joy, who had just returned home after a three-year absence; she fought to balance her relationship with Kayo against her embryonic career. In February of 1957, Mary Gray Harvey had developed breast cancer, and several months later Ralph Harvey had suffered a stroke, from which he made a slow recovery. Anne’s mother moved into the guest bedroom at 40 Clearwater Road. But in October of 1958, her cancer metastasized. For the next five months, Anne numbly monitored her mother’s slow decline as she visited the hospital room daily. On March 10, 1959, Mary Gray Harvey died. Three days later she was buried in the Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge.

In April, her father announced plans to marry again. Anne was appalled. She attempted to intervene, but he stood firm. Early in June, several hours after he had lain down for his customary Sunday nap, the maid found him dead of a cerebral hemorrhage.

Within four months, both Anne’s parents had gone, leaving a small legacy for their third daughter: a mink coat, a diamond, a few rare books, a ruby, and some stocks and bonds. They could not know that the richest inheritance they had left was an abundance of unvoiced emotion which would fill Anne’s poetry for years to come.

[To Mary Gray Harvey]

[40 Clearwater Road]

Christmas Day—1957

Dear Mother,

Here are some forty-odd pages of the first year of Anne Sexton, Poet. You may remember my first sonnet written just after Christmas one year ago. I do not think all of these are good. However, I am not ashamed of them. They are not in chronological order, but I have arranged them in a sort of way, in a sort of a story. But not too much or too well. I have tried to give a breather between the more difficult ones that use a more modern idiom. A few are obscure. I do not apologize for them. I like them. Mood can be as important as sense. Music doesn’t make sense and I am not so sure the words have to, always.

These are for you to do with as you wish. If you want to send them to that man in New York—do so. Simply put them in a manila envelope and address and fold (inside the other with the manuscript) another return envelope. (enclose some) Take these both to the post office and have them weighed and put postage on both. I feel that this is the only gracious way to ask anyone to read (and then return) poetry. And do the same with Merrill Moore. I sort of hope you won’t separate and fold some for mailing in a regular envelope as then they will never get back together again. However, do as you wish, they are yours (short of telling someone to publish them).

I know that they are lousy with typographical errors but I did my best—am not a graduate of Katie Gibbs and have a peculiar lack of spelling know-how.

I think my favorite poem is the first in the book (this may be because it is fairly recent—poets always prefer their latest things I hear—and it seems so). As you can see I have developed no one style as yet. But at first it is better, and is sort of chain verse. Both of these were difficult but fun—rather like a crossword puzzle. There are no sonnets. I am not ready for sonnets yet, somehow.

I hope you can have some fun with them. Now if you meet some interested person you will have these to show. Although it is a rarity to find anyone even willing to read poems—or poetry of my voice. Although there is nothing new in the manner in which I have written these, it seems new to most poet tasters. I do not write for them. Nor for you. Not even for the editors. I want to find something and I think, at least “today” I think, I will. Reaching people is mighty important, I know, but reaching the best of me is most important right now.

I did not win the Ingram Merrill Foundation Contest. However, this is just a start for me … I imagine I can always get printed from the psychiatric angle with preface by Dr. Martin—but he won’t talk about it until therapy is over—and by then I may not want to do it anyhow … There are lots of contests for first books of poetry that have real merit—most usually no money but a real start … I hope I am going to continue to improve and if I do I’m going to aim high. And why not.

I love you. I don’t write for you, but know that one of the reasons I do write is that you are my mother.

Love,

Anne

As the workshop with John Holmes drew to a close in the spring of 1958, she gained the confidence to send her poetry to well-known journals. “For Johnny Pole on the Forgotten Beach” [TB] was accepted by The Antioch Review in late May when she received a letter from one of their editors, Nolan Miller.

She liked to say that Miller and The Antioch Review discovered her, despite the fact that she had already published elsewhere. But it was true that after her Antioch appearance some of the better-known magazines in the country did begin to publish her work. Through Miller she applied for and received a scholarship for the Antioch Summer Writers’ Conference in August, going expressly to study with W. D. Snodgrass, then her favorite poet.

[To Nolan Miller

THE ANTIOCH REVIEW]

40 Clearwater Rd.

June 1st, 1958

Dear Mr. Miller:

[…] I am twenty nine (am not sure if this qualifies me as a “young writer”) and have been writing for about a year. I have been published in The Fiddlehead, The Compass Review (reprinted in The New York Herald Tribune), and have just received an acceptance from The New Orleans Poetry Journal (for a really long poem—which is pleasing). I have started to get quite a bit of encouragement from various editors; i.e., Ralph Freedman at The Western Review, Karl Shapiro at the Schooner, and Accent and the other morning received a phone call from one of the editors of Audience asking for more poems (ten, he said) as they liked one and wanted to print more than one. I have about twenty rejection slips from Howard Moss at The New Yorker saying “please send more” (am not sure what this means as they add up each week, after week—but it seems encouraging) also a couple of personal letters from Anne Freedgood at Harper’s and also The Atlantic … I didn’t mean to get going on what might happen but hasn’t, however the list of published looked so small.

I had been thinking of applying for your scholarship before I received your letter because it looks like the best one. However, did not because of the long trip out there which is an expense. I had even asked John Holmes (we are in a workshop together) if he would write a letter for me and he had agreed to do this. However, I guess I don’t need his letter now.

I would particularly like to meet W. D. Snodgrass because his poem “Heart’s Needle” startled me so when I read it, that I just sat there saying “Why didn’t I write this”. I admire his style and know that I need to study with someone I feel this way about.

Am writing this in a rush so that I can mail the revision of “Johnny Pole” [TB] tonight. I excuse this hurried and rambling letter (to myself at 1:00 A.M.) by saying that poets just aren’t expected to write sensible letters—just poems. Hope also you will forgive the fading type—am in need of a new ribbon.

Many thanks for giving me the chance to revise this poem as I knew it needed it—just needed someone to tell me.

Sincerely,

Anne Sexton

When Anne met W. D. Snodgrass at the Antioch Writers’ Conference, she fulfilled one of her first ambitions: to establish personal contact with a worthy mentor. Immediately following her return to Newton, she began an intense passionate correspondence with Snodgrass which set the pattern for many later friendships-by-letter.

[To W. D. Snodgrass]

40 Clearwater Road

August 31st—[1958]

Dear Mr. Snodgrass honey—

I have three pictures of you (and others) on my desk—they are placed there for inspiration. They do not work. But they will. You look sleepy in this one and Jan [Snodgrass], beside you, looks earnest and sweet with that one curl promising something. In another you are busy telling a bunch of sitting ducks something from your desk. Here you are looking young and rather handsome by the mike and Jessy West. She must be telling you how [illegible] genius you are or something—else why do you look so humble and pretty? I like your pictures—otherwise I wouldn’t believe it … some funny dream I walked through … I do bel...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Publisher’s Note

- Editors’ Note

- Prologue: Young (1928–1957)

- Chapter I: The Business of Words (December 1957–September 1959)

- Chapter II: All Her Pretty Ones (October 1959–December 1962)

- Chapter III: Some Foreign Letters (January–October 1963)

- Chapter IV: Flee on Your Donkey (November 1963–May 1967)

- Chapter V: Transformations (May 1967–December 1972)

- Chapter VI: To Tear Down the Stars (January 1973–October 1974)

- Epilogue

- Image Gallery

- Index

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright Page

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Anne Sexton by Anne Sexton, Linda Gray Sexton,Lois Ames, Linda Gray Sexton, Lois Ames in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.