- 121 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

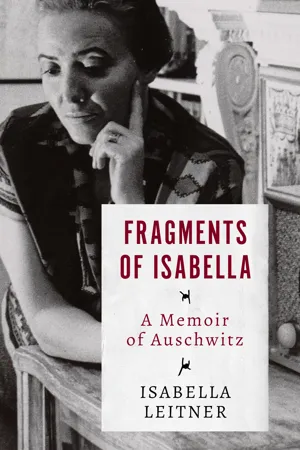

The deeply moving, Pulitzer Prize–nominated memoir of a young Jewish woman's imprisonment at the Auschwitz death camp.

In 1944, on the morning of her twenty-third birthday, Isabella Leitner and her family were deported to Auschwitz, the Nazi extermination camp. There, she and her siblings relied on one another's love and support to remain hopeful in the midst of the great evil surrounding them.

In Fragments of Isabella, Leitner reveals a glimpse of humanity in a world of darkness. Hailed by Publishers Weekly as "a celebration of the strength of the human spirit as it passes through fire," this powerful and luminous Pulitzer Prize–nominated memoir, written thirty years after the author's escape from the Nazis, has become a classic of holocaust literature and human survival.

This ebook features rare images from the author's estate.

In 1944, on the morning of her twenty-third birthday, Isabella Leitner and her family were deported to Auschwitz, the Nazi extermination camp. There, she and her siblings relied on one another's love and support to remain hopeful in the midst of the great evil surrounding them.

In Fragments of Isabella, Leitner reveals a glimpse of humanity in a world of darkness. Hailed by Publishers Weekly as "a celebration of the strength of the human spirit as it passes through fire," this powerful and luminous Pulitzer Prize–nominated memoir, written thirty years after the author's escape from the Nazis, has become a classic of holocaust literature and human survival.

This ebook features rare images from the author's estate.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fragments of Isabella by Isabella Leitner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

EPILOGUE

THIS TIME IN PARIS

By Irving A. Leitner

The first time Isabella and I vacationed in Europe, we had been married only four years. It was 1960, and we left Peter, our one-year-old, in upstate New York with Isabella’s older sister. When we returned nearly a month later to retrieve him, he fidgeted and cried for almost an hour before accepting us back as his rightful parents. Instinctively, at the age of one, he knew how to make us feel guilty for abandoning him while we traipsed about the continent. This time, fifteen years later, we took Peter along, as well as his thirteen-year-old brother, Richard.

On that first trip, we had spent a week in Paris, a week in Rome, and ten glorious days skittering about in general—from Cannes on the Riviera to Florence, Venice, Verona, Milan, Zurich, and London. It was exciting, exhilarating, and exhausting, and we lived on the accumulated memories for a decade and a half. Pointedly, we avoided setting foot in any German city and swiftly moved out of earshot whenever we heard German spoken.

Our resolve in 1960 to avoid anything remotely German was tinged with irony, however, for as it turned out, the dearest friend we made on that trip, and the person who guided us daily around Paris, was a middle-aged German woman to whom we had carried a letter of introduction from a mutual friend in the States. But then, Madame D was an expatriate who had left her native land in revulsion during the period of Hitler’s ascendancy and had worked in the French resistance movement during World War II.

Madame D walked with us endlessly and tirelessly, conversing softly in fluent English while we avidly absorbed the sights, sounds, and smells of the magnificent streets and boulevards. On our final day in the city, she took us to the old and shabby Jewish quarter, where a shrine had been erected as a memorial to those who had been systematically murdered in the Nazi extermination camps. It was late in the day, and long shadows were falling as we approached the memorial. Madame D and I slackened our pace, but Isabella quickened hers. Suddenly, Isabella broke down and wept uncontrollably. Madame D whispered, “Go to her. Comfort her.” I moved swiftly to Isabella’s side. The three of us stood there in the gathering darkness, forlornly contemplative—I with my arms about Isabella, Madame D a respectful distance behind. After a while, we simply turned and left.

In Venice, about ten days later, some mysterious impulse drove us once again to seek identification with our roots. We sought out the old ghetto quarter, trod the ancient streets, and walked the Rialto bridge. A vision of Shakespeare’s Shylock materialized for me: “… many a time and oft/ In the Rialto, you have rated me/ … You call me misbeliever, cut-throat dog, /And spit upon my Jewish gaberdine.…”

In Rome, on a Friday evening, we asked a priest to direct us to a synagogue. He looked at us with incredulity, then taken with our audacity, led us there himself. He had never visited the area, he confided in halting English, and felt it was as good a time as any to see what a synagogue looked like in the city of churches.

When we arrived, a sprinkling of elderly worshipers were standing about in front of the building. The services had not yet begun, and pleasantries were being exchanged. At the unfamiliar sight of the black-frocked priest and the alien young couple halting before their synagogue, the Roman Jews stopped talking and stared at us with suspicion.

Unable to speak Italian, we asked the priest whether he would explain to the people that we wished them no harm, that we were only visiting. But our request was more than the priest felt comfortable with. He demurred and we understood. He agreed, however, to wait for us while we peeked inside. I then covered my bare head with a raincap, and Isabella and I walked into the house of worship.

Immediately beyond the outer door, an attendant directed Isabella in Italian to a flight of stairs at the left. Evidently, this was an Orthodox synagogue, and as was customary, men worshiped separately and apart from women. Since we actually had not come to pray, only to “see,” Isabella pointed to her watch and said in English, “Just a minute,” and raced up the stairs while I proceeded through the doors on the ground floor.

I really don’t know what we expected to see, but somehow it felt right that we should be there, even for only a minute. When Isabella met me outside a few moments later, we rejoined the priest, who was waiting patiently on the other side of the street.

“Why didn’t you stay to pray?” he asked.

“We’re not religious,” I said. “We were just curious.”

“I was impressed,” said the priest. “There were more worshipers here than in many of Rome’s churches. A lot of the churches are empty every Sunday.”

“Most of the worshipers tonight were old,” I said, as though my comment somehow explained the phenomenon.

In London and in Paris in 1975, ancient ghettos and synagogues were quite remote in our minds. Isabella and I wanted to show our sons the sights the two capitals were famous for. We didn’t want to be sophisticated. We wanted to gape and gawk and see things perhaps a bit as we remembered them. And so we did, and relished every single moment of it.

This time in Paris, however, we did not see our old German friend Madame D, who was out of town on holiday. But we did see our Turkish friend Jessica and her American husband, George, whom we had met in the States some years before. The day before we were to return to New York, we arranged to spend the afternoon visiting the ancient cemetery of Père-Lachaise, where such diverse personalities as Honoré de Balzac, Sarah Bernhardt, Oscar Wilde, and Frédéric Chopin were buried, among the tombs and bones of thousands of other mortals and immortals.

Isabella and I still had not forgotten the visit we had made to a cemetery in Florence back in 1960. It was a Saint’s Day then, and the sight of processions of people carrying lighted candles and flowers, wending their way in the soft evening light through the statuary, tombs, and graves, was deeply lodged in our memories. We hoped now in Paris to recapture some of the feelings we had experienced then. We were disappointed, of course, but the visit to Père-Lachaise was not without its special moments.

As we moved along the narrow paths and lanes, we suddenly found ourselves in a relatively new section of the ancient cemetery—Jessica informed us that it was called the martyrs’ area—and there, rising hauntingly from the earth, one after the other, was a series of sculptures commemorating the murdered millions of the Nazi concentration camps.

One sculpture, dedicated to the victims of Maidanek, depicted a towering flight of steps on which a child was struggling upward; another, a desolate, faceless figure, recalled the nameless horrors of Auschwitz; a third, with the names of several Vernichtungslager chiseled at the base, showed three skeletal figures clawing at the sky.

Until that instant, Isabella and I had managed to dwell only on the joy of our trip—time enough later for current events, current wars, current crises. For the interlude of July 1975, there was to have been no ugly past, no bitter memories—only pleasure and enrichment.

Still, there had been small, disturbing intrusions, reminders of another time, another place. Fifteen years earlier, everywhere we went we had met American tourists by the scores; now the tourists seemed to be mainly Germans or Japanese. It was almost impossible to avoid the Germans. Isabella, for the most part, tried to ignore them. “I don’t mind the young ones so much,” she said; “they are an innocent generation. It’s the older ones …”

But now, in a doleful corner of Père-Lachaise, the fragile fantasy we had so carefully nourished was suddenly demolished. Yet this time, unlike 1960, there were no tears, no heart-wrenching tugs, no need for consolation. This time Isabella wanted only a photograph as a personal remembrance. She posed briefly for Peter, and we left the cemetery, Jessica and her husband going their way, and we returning to our hotel.

Since our second day in Paris, we had made it a nightly ritual, before retiring, to spend some time in a modest café near our hotel, to relax, chat, and reconstruct the day’s events. With our departure scheduled for the following noon, this was to be our last evening at the Café Cristal. The weather, which had been glorious for most of our trip, had suddenly turned dismal. A light rain was falling, casting a certain moodiness over us as we entered the glass-enclosed terrace.

The unexpected jolt at Père-Lachaise, coupled with the knowledge that our vacation was ending, had had a sobering effect upon us all. Still, we were determined to extract every last bit of experience possible and tuck it away as a joyful memory of Paris. And so we sat down and gave the waiter our orders.

Isabella had just lit one of her short French cigarettes, and four foaming cups of café au lait had barely been placed on our table, when all at once a group of ten or twelve tourists, both men and women, streamed through the two terrace doors and out of the rain. Amid much stamping of feet, doffing of hats and coats, and bantering remarks, the newcomers began to move the tables and chairs about so that they could all be together. The problem for them seemed to be our small table, which was centrally located against the terrace wall, preventing them from grouping all the tables on either one side or the other.

Suddenly, a feeling of dismay clutched me, for in a flash I realized that all the men and women were Germans.

“Who do you think they are?” Isabella whispered.

“Danes,” I replied, in an effort to shield her from the truth. The irony of this development coming so soon upon the heels of Père-Lachaise seemed almost too much to bear.

The Germans, appearing somewhat exasperated at our presence, finally decided to divide their party into a semicircle. Two men took a table to our left, two to our right, and the remainder shoved their tables together in the open area behind us. Isabella, with her back to the terrace wall, as well as the boys and I, felt literally surrounded.

With growing anxiety, I watched Isabella’s face carefully for the first signs of recognition. She was obviously intrigued by all the fuss and commotion. As the man at her elbow glanced in our direction, a broad, red-faced grin expanding his jowls—an apparent overture of friendliness—Isabella suddenly asked, “Danish?”

“Nein,” replied the stranger, “Deutsch. Von München.”

Isabella reacted as though acid had been hurled in her face. She seemed to shrivel in her seat. She covered her eyes to blot the man out of her sight. An instant later, with head lowered and lids tightly closed, she placed her palms over her ears, trying to block out every sound.

The grin on the red-faced German vanished. With a guttural murmur and a scraping movement, he readjusted his posture. He mumbled something to his companion, and from the corner of my eye, I could see that ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Praise for Fragments of Isabella

- Title Page

- Epigraph

- New York, May 1945

- May 28, 1944–Morning

- May 28, 1944–Afternoon

- My Father

- Main Street, Hungary

- A New Mode of Travel

- The Arrival

- My Potyo, My Sister

- Grave

- “Eat Shit”

- Philip

- The Baby

- Casting in Auschwitz

- Musulmans

- Irma Grese And Chicha

- Rachel

- Serenity

- Birnbaumel

- Hitting the Celt

- My Heart is Beating

- In The “Hospital” At Birnbaumel

- January 22, 1945

- The Barn

- January 23, 1945

- The House

- January 24, 1945

- January 24, 1945–Evening

- Rachel, I Salute You

- January 25, 1945

- The U. S. Merchant Marine Ship

- My Sorrow

- Mirror

- May

- Peter

- Richard

- Epilogue

- Image Gallery

- About the Author

- Copyright Page