- 324 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Twenty-five hundred years ago, Pythagoras taught that the simple counting numbers are the basic building blocks of reality. A century and a half later, Plato argued that the world we live in is but a poor copy of the world of ideas. Neither realized that their numbers and ideas might also be the most basic components of the human psych: archetypes. This book traces the modern evolution of this idea from the Renaissance to the 20th century, leading up to the archetypal hypothesis of psychologist C. G. Jung, and the mirroring of mathematical ideas of Kurt Gödel.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Jungian Archetypes by Robin Robertson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE RENAISSANCE IDEAL

The eminent historian of science Alexandre Koyré liked to emphasize the difficulties in conception and philosophy that accompanied the revolutionary shift in thinking required of the Renaissance thinkers. Their transition in advancing from the closed world of Aristotle’s universe to the infinite world of the post-Copernican era was in many respects a painful and traumatic one, but profound in its implications for the subsequent history of Western thought.1

LOOKING OUT AT THE WORLD

Though the growth of Christianity had been the greatest unifying force in the history of the Western World, it effectively brought an end to speculative thought about nature. During the thousand years of the Middle Ages, between the fifth and the 15th centuries, God’s word was considered a better guide than human experience or reason. Scholastic philosophers were satisfied to perfect the dialectic and analytic methods of Aristotle. Since scholastic philosophy proceeded from religious dogma, not from observed fact, the beginnings of science were set back many centuries.

Advances in knowledge start with questions: where do we come from? Where are we going? What is the nature of the world? What is our nature? What is the relationship between our nature and the nature of the world? Great changes in worldview involve not only new answers to these eternal questions, but perhaps more importantly, new ways of asking the same questions. During the thousand years of the Middle Ages (the fifth to the 15th century), the Western world largely accepted that God created the world and so asked: What is the nature of God? What is the relationship between God and humanity? Most medieval thinkers started from the presumption of a static world over which they had little or no control. Their curiosity centered around God, not the world. According to medieval historian Etienne Gilson, there were two kinds of medieval thinkers: those who believed that “since God has spoken to us it is no longer necessary for us to think,” and those who believed that “the divine law required man to seek God by the rational methods of philosophy.”2 Both types proceeded from fixed premises; the idea that thinkers should repeatedly check both premise and conclusion against experience was alien to the main stream of Medieval thought.

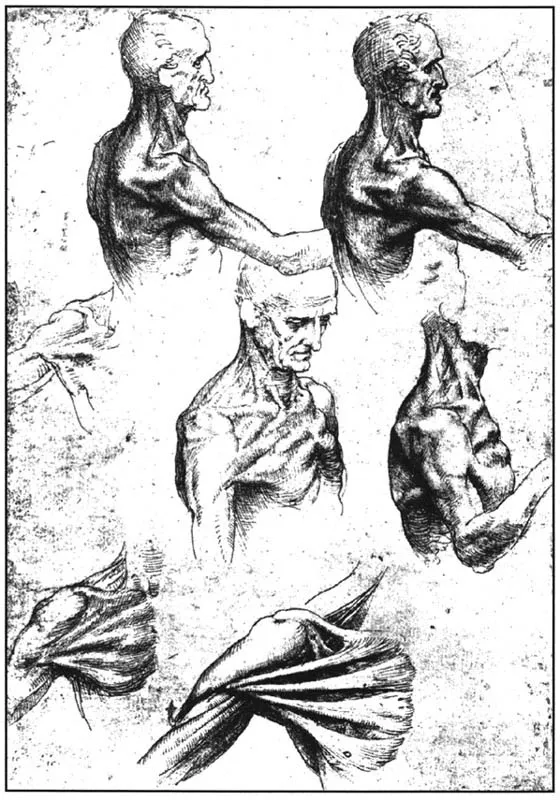

During the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries, Renaissance thinkers suddenly awoke, looked at the world with new eyes, and asked a different question: What is the nature of the world? That question caused them to turn their eyes outward toward the world and to begin to describe what they saw there. When that description led to new questions, they proposed solutions, then turned once more to the world to check the validity of their conclusions. The Renaissance ideal was aptly expressed in statements by Leonardo Da Vinci [1452–1519], such as “Experience never errs; it is only your judgements that err by promising themselves such as are not caused by your experiments,” or “all our knowledge has its origin in our perceptions.”3

Da Vinci was able to combine this belief in the power of experience with a belief in God because of a changing view of God. Da Vinci addressed his God with “O admirable impartiality of Thine, Thou first Mover; Thou hast not permitted that any force should fail of the order or quality of its necessary results.”4 In other words, God had done his job by creating an ordered world; now it was up to us to use our reason to discover the rules that governed that world. Da Vinci said that: “the senses are of the earth; Reason stands apart in contemplation.”5 Once that step had been taken, it was inevitable that we would eventually turn reason upon itself, and try to describe the nature of the mind. However, that wasn’t to occur until long after the intoxicating first flush of discovery of the physical world had passed.

This new combination of freedom and responsibility produced a flourishing of genius that was unprecedented in European history. Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Erasmus, Luther, and Copernicus were all born within the fifty-year-period between 1450 and 1500.6 Erasmus and Luther each fought the intellectual domination of the “Holy Mother the Church” in his own characteristic way. Erasmus, a man of the mind, tried to pursue truth to its logical conclusions regardless of church dogma. Luther, “that most unphilosophical of characters,”7 broke the domination of the Church and created the Protestant movement. Each was attempting to give humanity a central place in the scheme of things, yet each was deeply religious.

Michelangelo [1475–1564] and Da Vinci for the first time made humanity the central subject of art. Medieval art dealt with humanity only in generalities; its real subject was God. Michelangelo created art that pictured not only a particular man or woman, but more than that, a heroic man or woman. Michelangelo’s art cried that we could all be as the gods. Da Vinci, the quintessential Renaissance artist, created art that captured ordinary reality so extraordinarily that the viewer began to realize what a mystery lay within each person, each object. Both were, in their characteristic styles, bringing God down from the heavens, and placing divinity in the world.

LEONARDO DA VINCI’S DRAWINGS.

There were limits, however, to this new Renaissance ideal. Just as Medieval thinkers failed to question their premises and check them against reality, Renaissance thinkers didn’t think to question the validity of the act of observation itself. They assumed that their observations were of necessity accurate representations of the world. During the Middle Ages, the world was accepted as God’s creation and, therefore, eternal and immutable. During the Renaissance, the world became a mystery to be examined and explained, but the mind doing the examining and explaining remained unquestioned. There was an implicit belief that “the human mind is, in effect, a mirror that reflects without distortion the indwelling structure of the external world.”8

This new Renaissance view regarded human beings primarily as observers and the physical world as the proper object of their observation. This separation of observer from observed led to a new stage of consciousness, in which eventually all humanity became aware of its individuality. Without that separation, it would have been impossible for art and science to develop. Without it, there would have been no mass democracy, no social or religious reform. Yet, despite the necessity for humanity to take this step, the fact remains that it is essentially based on a false assumption, for there is no inherent separation of observer from that which is observed. The assumption that there is would create not only wondrous new discoveries, but also a deep and troubling sickness of the soul. This new view of reality would develop into the rationalist/materialist position that separated mind and body, and alienated human beings first from the world, then from each other, and finally from their own inner experience. Eventually we would reach the point at which we are now, a point where the rift has to be healed if we are to advance further.

MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE

The originality of mathematics consists in the fact that in mathematical science connections between things are exhibited which, apart from the agency of human reason, are extremely unobvious.9

Mathematics has been used as a tool from humanity’s earliest times. No human community has been identified which does not use at least the smaller integers. Nomadic cultures, constantly on the move, needed mathematical tools to calculate direction and distance. Later, agricultural societies needed more advanced mathematical tools to count the population, draw property lines, to record accurately the progress of the seasons on which their crops depended, to construct a calendar, for sales and bartering, to calculate inheritance: in short, tools of counting and measurement. From its inception, mathematics developed along two frequently intertwined paths: arithmetic (the study of number),10 and geometry (the study of space). Much of our story in the pages to come revolves around the relationship between these two paths, their progressive differentiation from each other, and the eventual realization that they represented two different approaches to reality.

Both conceptual approaches are so old that it is impossible to formally identify their beginnings. Arithmetic deals with the separate, the discrete, the individual; geometry with the continuous, the connected, the whole. Arithmetic began with the individuality of the small counting numbers and advanced by studying the many and varied relationships between those numbers. Geometry began with the space that surrounds us, and modeled that reality with ideal points and lines, figures and solids. The combination of the two approaches provided ways to use measured quantities to calculate the lengths of sides and the sizes of angles which had never actually been measured.

Mathematics as a science commenced when first someone, probably a Greek, proved propositions about any things or about some things, without specification of definite particular things. These propositions were first enunciated by the Greeks for geometry; and, accordingly, geometry was the great Greek mathematical science.11

EUCLID

By 600 B.C., Greek mathematician Thales had already taken geometry out of the stage where it was merely a co...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Praise for Jungian Archetypes

- Title Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Dedication

- Preface

- Chapter 1. The Renaissance Ideal

- Chapter 2. The Birth of Science

- Chapter 3. What Do We Know and How Do We Know It?

- Chapter 4. Pragmatic Responses

- Chapter 5. Founders of Experimental Psychology

- Chapter 6. Founders of Clinical Psychology

- Chapter 7. Cantor’s Set Theory of Transfinite Numbers

- Chapter 8. Sigmund Freud

- Chapter 9. Logic’s Tower of Babel

- Chapter 10. Background for Jung’s Psychology

- Chapter 11. Jung’s Model of the Psyche

- Chapter 12. Background for Gödel’s Proof

- Chapter 13. Archetypes of Development: Shadow

- Chapter 14. Archetypes of Development: Anima/Animus

- Chapter 15. Archetypes of Development: Self

- Chapter 16. Gödel’s Proof

- Chapter 17. Alchemy as a Model of Psychological Development

- Chapter 18. Mysterious Union

- Chapter 19. Number as Archetype

- Bibliography

- Index

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright Page