- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

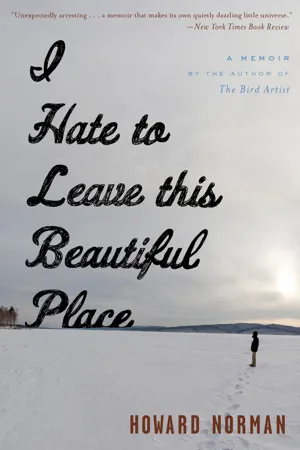

"Some books celebrate the human condition; others commiserate with us. This memoir does both." —Helen Oyeyemi, NPR

This spellbinding memoir by the National Book Award–nominated author of The Bird Artist begins with a portrait, both harrowing and hilarious, of a midwestern boy's summer working in a bookmobile, under the shadow of his grifter father and the erotic tutelage of his brother's girlfriend. Howard Norman's life story continues in places as far-flung as the Arctic, where he spends part of a decade as a translator of Inuit tales—including the story of a soapstone carver turned into a goose whose migration-time lament is "I hate to leave this beautiful place"—and in his beloved Point Reyes, California, as a student of birds.

Years later, Norman and his wife lend their Washington, DC, home to a poet and her young son, and a subsequent murder-suicide in the house has a profound effect on them. In this "unexpectedly arresting" memoir, life's unpredictable strangeness is fashioned into a creative and redemptive story ( The New York Times Book Review).

"Norman uses the tight focus of geography to describe five unsettling periods of his life, each separated by time and subtle shifts in his narrative voice. . . . The originality of his telling here is as surprising as ever." — The Washington Post

"These stories almost seem like tall tales themselves, but Norman renders them with a journalistic attention to detail. Amidst these bizarre experiences, he finds solace through the places he's lived and their quirky inhabitants, human and avian." — The New Yorker

This spellbinding memoir by the National Book Award–nominated author of The Bird Artist begins with a portrait, both harrowing and hilarious, of a midwestern boy's summer working in a bookmobile, under the shadow of his grifter father and the erotic tutelage of his brother's girlfriend. Howard Norman's life story continues in places as far-flung as the Arctic, where he spends part of a decade as a translator of Inuit tales—including the story of a soapstone carver turned into a goose whose migration-time lament is "I hate to leave this beautiful place"—and in his beloved Point Reyes, California, as a student of birds.

Years later, Norman and his wife lend their Washington, DC, home to a poet and her young son, and a subsequent murder-suicide in the house has a profound effect on them. In this "unexpectedly arresting" memoir, life's unpredictable strangeness is fashioned into a creative and redemptive story ( The New York Times Book Review).

"Norman uses the tight focus of geography to describe five unsettling periods of his life, each separated by time and subtle shifts in his narrative voice. . . . The originality of his telling here is as surprising as ever." — The Washington Post

"These stories almost seem like tall tales themselves, but Norman renders them with a journalistic attention to detail. Amidst these bizarre experiences, he finds solace through the places he's lived and their quirky inhabitants, human and avian." — The New Yorker

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access I Hate to Leave This Beautiful Place by Howard Norman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatur & Literarische Biographien. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

LiteraturSubtopic

Literarische BiographienGrey Geese Descending

MY CANADIAN UNCLE, Isador, knew the actor Peter Lorre. In fact, Lorre had arranged for a bit part in a movie, The Cross of Lorraine, for Isador. And Isador insisted on calling Lorre, a Hungarian Jew, by his original name. “If Laszlo Lowenstein doesn’t wish to acknowledge he’s Jewish, that’s his professional choice,” Isador said.

In September of 1969 I moved to Nova Scotia, because a friend of mine was going to live in Amsterdam for a year and said I could sublet his room in the Lord Nelson Hotel in Halifax for thirty-five dollars a month. I had no prospects but this cheap room. And that was enough to get me there.

I was adrift. Between graduating from high school in 1967 and moving to Halifax in 1969, I had lived in Toronto, Ottawa, Berkeley, and Vancouver. As for employment, for eighteen months I wrote pop music reviews for the Interpreter, an alternative newspaper based in Grand Rapids. One of my assignments was to cover a concert in Vancouver by Donovan, an immensely popular Scottish singer and songwriter. The next assignment was to write an article—my idea—about the Institute for the Study of Nonviolence, in Palo Alto, California. To get from Vancouver to the institute, I purchased a jeep for $350 and began to drive south. It was my first time on the West Coast. I stopped in Inverness and Point Reyes Station, California, where I stayed for a dollar a night in a kind of fisherman’s shack at the end of a dock jutting into Bodega Bay. Under the dock, ducks found shelter from the rain. Pelicans were a constant presence. By the time I had walked three trails at the Point Reyes National Seashore, I had planned to return there.

When I finished my article on the Institute for the Study of Nonviolence, having met its two founders, Joan Baez and Ira Sandperl—the most enthralling intellect I’d ever met—my antiwar convictions solidified. Yet when I left Palo Alto I still felt unsettled. I spent the summer in a cottage in Jeffersonville, New York, a twenty-five-minute drive from Max Yasgur’s farm and the Woodstock festival. I attended this monumental event. At the end of that summer, my only goal was the cheap hotel room in Halifax.

So I found myself in a Canadian city that I was determined to know better. I also had designs on writing radio plays for the CBC. I thought I would trace one family’s story from their fleeing Hitler’s persecution to their arrival through immigration at Halifax’s Pier 21—a major port of entry for refugees—and their subsequent life in the city. I had outlined a ten-part drama on this subject, but I’d never written for radio before. Truth be told, I simply wanted to be able to say to someone, “I write for radio.” Just that sentence gave me inspiration, as fatuous as it may sound. In fact, I’d seen a CBC advertisement for “auditions,” which meant you could send in a radio play and they would decide whether to use it or not. I was twenty; it all seemed like a good idea at the time. It was my only idea at the time.

For a few evenings I’d been listening to the jazz pianist Joe Sealy’s record Africville Suite. Sealy’s father was born in the section of Halifax known as Africville. Sealy himself was working there at the time of the unspeakable “relocation” of the mostly black community during the years 1964 through 1967, and Joe Sealy composed the Africville Suite in memory of his father. My girlfriend Mathilde Kamal’s mother was also raised in Africville. I’d been thinking about the last conversation I had with Mathilde, two days before her four-passenger charter plane, subjected to blizzard conditions and possibly pilot error, slammed to the frozen ground in Saskatchewan—the bleak winter landscape that was the exclusive subject of her latest watercolors.

Mathilde was twenty-six when I met her. She was worldly, and I was a pin stuck in a street map of Halifax, at 416 Morris Street, my address that autumn and into the winter of 1970. Too often self-deprecation can be a form of self-regard: I’m nothing—praise me. To my mind, self-deprecation is useless except when it is used as the first rung on a ladder of self-reckoning. Once at a restaurant, before we ordered dinner, when I’d lamented the great differences in our educations and experiences—“Mathilde, after all, you’ve lived all over Europe!”—she tapped her wine glass with a spoon as if about to offer a toast. “Distasteful way of thinking, my friend,” she said. “You are what you are. I love you. Now let’s order. I’m very hungry.”

But by any standard, Mathilde was worldly. She had been born in Morocco of a French father and a Canadian mother—her parents had moved to Morocco the year before Mathilde was born—educated at the Sorbonne, had had exhibitions of her work in London and Bruges, and had been married for a year to a much older man, a museum curator in Amsterdam. After finalizing her divorce, she moved to Halifax, where she lived in a shabby two-room apartment on Robie Street near Citadel Park. “I moved to Halifax because the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design offered me a course to teach,” she’d said. “I wasn’t good at it. But it paid the rent and I liked the city. So here I am.”

The moment we met, in early September 1969 in a café on Hollis Street, I was attracted to her, but not in a head-over-heels way. I think she sensed this, and it put her at ease. Mathilde had, as she put it, “suffered adoration” in her life. She often spoke autobiographically, but seldom confessionally. When she was nineteen, her future husband had pursued her, which she emphatically said bored her to tears. “Because men look, doesn’t mean you look back.” She had aphorisms about such things; some were more convincing than others.

During the first months of our courtship, it was almost entirely a matter of her fixing on me her affection and commitment. She did this with her eyes wide open, with full agency, and without compromise, and because it pleased her. She wanted life to be different, so she made it different. This, for the first time in my life, made me feel attractive, but it was because she intensified the attractiveness of life, and drew me into that. It was like being invited into a philosophy. I wasn’t passive, I was just riding a strong wave. She had purpose. She had talent and flair. She liked to quote some movie or other in a defiant, Bette Davis voice: “Like I said, I don’t quake when things get tough, and I don’t make deals with the devil.” I was what might be called a work in progress; Mathilde already had definite refinements and opinions enough to fill a thick volume. Her opinions always struck me as born of experience, but of course they couldn’t all have been.

With Mathilde I was taken by surprise, grateful, but resistant, questioning, and vigilant about complications—and then slowly, painstakingly, I realized I was indeed head over heels. We held hands everywhere. One summer day I called her darling. This just flew out; it was not a word I’d heard used by my parents, nor had I ever used it myself. (I’d heard it in the movies.) Mathilde used it often and freely. She said it with feeling. It all seemed a lot to fit into less than a year’s time. Then Mathilde was gone.

Mathilde first exhibited her work in 1967, part of a group show in a warehouse space in north London. I saw only photographs of the paintings: eight works in oil that were as far in aesthetics, style, and subject matter from her future watercolor landscapes as could possibly be imagined. For one thing, the early paintings were full of people; her final landscapes not only had no people in them, but the settings suggested that people had never lived in them.

Her part of the London exhibit was called “Memories of Africville.” The title referred to her mother’s memories and to things Mathilde had discovered while doing library research. To the extent that these paintings comprised a cumulative portrait of hardscrabble life in Africville, there was a near-documentary immediacy to them. Mathilde, at that young age, used paint in a way she herself said was influenced by Chaim Soutine, whose paintings she’d studied in Paris, where Soutine had lived. “Paint put on thickly, emotion put on thickly,” she explained. “Even his trees are emotional.” She made portraits of black seamen, Pullman porters, domestic servants. She painted meetings of the African Baptist Association and local churches. There were three paintings of the Africville prison. One work depicted a solid-waste facility built to take the filth of a neighboring town, another showed people scavenging for clothes and lengths of copper pipe in a garbage dump. There was a painting of children in an infectious-disease hospital.

When referring to these documentary works, Mathilde was measured if not dismissive. “I don’t regret painting them. It felt like I was saying to my mother, I know where you come from. But I gave every last painting away. Finally they felt more like an obligation, things I was supposed to paint. Nothing wrong with that, but I couldn’t paint out of obligation anymore, pure and simple. But don’t tell me life isn’t strange. Who could’ve predicted, the first time I went out there, the effect Saskatchewan would have on me? It was like my soul had new eyes. I felt my soul come alive. Like in my past life, I was actually part of that landscape. I thought, Now I’m me, present-day Mathilde, but painting my former self. That’s probably kind of Buddhist.”

“We should elope,” Mathilde said. We were walking on Water Street near Historic Properties. “I’ve always wanted the experience of eloping.”

“Elope to where?” I asked.

“I was thinking Saskatchewan.”

“Knowing you,” I said, “you’d want to get married standing out on some godforsaken prairie.”

“Godforsaken?” she said. “I don’t think that’s true at all. I find God out there.”

“An abundance of churches doesn’t necessarily mean hospitality.”

“What’s bugging you? Is it our age difference again? The age difference bothers you a lot, doesn’t it? Let me put it this way. I’ve already tried older. Now I’m trying younger.”

For whatever reason, hearing herself utter this made Mathilde double over in laughter. Other pedestrians out in the bitter cold that day stared at us. Then, as if by some telepathic communication, we both noticed we were standing in front of a small art gallery. Wordlessly we agreed to go inside. It had begun to snow. The gallery was nearly empty. Tea, hot cocoa, wine, cheese, and crackers were laid out on a long table. Mathilde was immediately drawn to a painting called Grey Geese Descending. I got two paper cups of cocoa and joined her.

Grey Geese Descending was about twenty-four inches wide and eighteen inches high, and showed five grey geese about to alight on a pond. Their wings were spread to slow and balance their gliding descent. One appeared to be mishandling its approach, its body slightly contorted, its feathers decidedly more ruffled than the others’, as if its flight through the mountain pass and valley in the background had been more harrowing, as though the gods of travel themselves had put up resistance.

Mathilde stepped back and pointed to the disheveled goose. “See, that’s what happens when it got confused.”

“I had no idea you could read the minds of Japanese geese.”

“I never told you that?” She was keeping things light.

“Melancholy day, isn’t it?” I said. “In the painting, I mean. Overcast sky and everything.”

“Geese may not get sad about the same things you get sad about. Besides, overcast skies are better to see birds by. Haven’t you noticed that?”

“Yes, I have.”

“I mean, you love to go out and look at birds over at Port Medway, and even at the harbor here in the city, right? I like to see crows against the grey skies out in Saskatchewan. Then there’s my seagulls everywhere that I love so much. That’s something we truly have in common, right? That and things that go on with us under the quilt. Tell me, do you like this painting or not?”

I said, “You make decisions, like or dislike, faster than me.”

We looked at all the paintings and some scrolls, drank hot chocolate and wine, and ate cheese and crackers, everything that was on offer. It was our dinner. We were in the gallery for about half an hour, I’d say. Then we repaired to a student café on Duke Street near the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. We took a window-side table. When our espressos arrived, Mathilde said, “I’ll elope with you if we can come to some agreement about that painting we just saw. And don’t act like you’re merely resigned to talking about this. I want you to be interested.”

Just then, for all her insistence, as she sat across the wooden table from me, her coat and scarf still on, I got lost in her physical self—entranced might be the word—as if I were memorizing her. This no doubt doesn’t speak well for me: shouldn’t one live fully in the moment. Still, there it was. Barely shoulder-length black hair with two red streaks swirled up in a topknot and tucked under her knitted hat, skin flushed from the cold, brown eyes wistful even when she was joyful, prominent cheekbones, and her nose—which, as she had put it, “I only liked after it was broken when I was playing high school lacrosse,” and which had been broken a second time when she’d taken a spill from a moped. She had a slightly tilted smile that thrilled me.

Almost without reprieve, we had been out of sync with each other, contentious, all without discussion, for about a week. The most vexing aspect of this was to experience the symptoms of Mathilde’s discontent without knowing if there was an exact cause. She’d been painting for upward of eighteen hours a day. I hadn’t discovered a passion even remotely comparable. I liked to read and look at birds and compose long handwritten letters. But I sensed that liking wasn’t enough to fill a life.

“Where are you?” she asked.

“Sorry, I drifted off.”

“We should talk about the painting. I think we saw it differently.”

We sat there until the café closed, which must’ve been midnight at least. Grey Geese Descending was ostensibly the subject at hand. But for the next few hours deeper information about each other was also being requisitioned. Hard to describe this, but I believe we both knew something was ending. Then, either you have to start a second romance within the first or all is lost. More likely, Mathilde knew it, and I didn’t want to know it. After her death, I understood that by presenting the offer—“I’ll elope with you if we can come to some agreement on the painting we just saw”—she might have intended it as a kind of fait accompli, since she knew in advance that we would not agree. To put it another way, if in the end this conversation wasn’t intended to be a kind of elegy, each sentence we spoke seemed tense with elegiac anticipation. Half an hour into it I wanted the conversation to stop, and Mathilde seemed about to ask the café’s proprietor to let us stay the entire night in order to continue it.

I thought Grey Geese Descending, in every specific and general aspect, was an allegory of sadness; conversely, Mathilde saw it as having captured “the mood of the painter and therefore the mood of the landscape itself.” She said, “You don’t really know enough about psychology to psychologize so much about this painting. That kind of talk keeps you from feeling the beauty of it.”

I said, “You’re the one who tried to tell me what that goose was thinking—that it was hesitating to land.”

“Stop reading yourself into the painting.”

On and on like that. It would have been wonderful if we were simply using different sensibilities to come to a mutual understanding, a duet of opposite natures, but this was more an exchange, in self-consciously subdued voices, of a maddening civility that might more characterize the first conversation between two people trying to get to know each other. Then, minutes before the café closed, Mathilde asked with huffy directness, “Did you realize that my saying we should elope was a marriage proposal?” I said, “But since you didn’t invite me to Saskatchewan—” Mathilde said, “We can elope right here in Halifax.”

Using a directory and the café’s telephone, we woke up a justice of the peace at one A.M. and walked to his house. After a few perfunctory questions, he said, “This can’t legally work. You, sir, are an American citizen, and you, madam, are a citizen of Morocco. Also, you need a witness.” Mathilde said, “We can be our own witnesses.” “Not on paper,” the justice of the peace said. We shrugged, apologized for waking him but not for the reason we had woken him, and left, acquiescing for the moment to international legalities.

Within an hour, in bed in Mathilde’s apartment, our uninhibited lovemaking was new and surprising. Something had let go. “I don’t care what anybody says. This feels like a marriage bed,” she said, then got up to smoke a cigarette and make coffee.

“Well, you’d know and I wouldn’t.”

I immediately regretted saying that, but she seemed to ignore it. Yet the very sweat on our bodies and bedclothes seemed to be the prescient fragrance of final melancholy. Our lips were sore and swollen, and we took separate hot baths.

The next morning, Mathilde left before I woke, two days earlier than she’d originally planned. From Regina, Saskatchewan, she sent a picture postcard of a man and woman eloping: the man had set a ladder against a house and was standing on the top rung, just outside the woman’s open bedroom window, through which she was handing him her suitcase. Through the living room window you could see the woman’s mother and father watching television. President Eisenhower was on the screen. There was a full moon in the sky. The scolding caption read: The moon makes these two act impetuously! Big mistake! Matilda’s own handwritten message was: I do.

I don’t know much about premonition. Nor would I necessarily recognize, let alone trust, its opportunities. Yet thinkin...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Advice of the Fatherly Sort

- Grey Geese Descending

- I Hate to Leave This Beautiful Place

- Kingfisher Days

- The Healing Powers of the Western Oystercatcher

- Sample Chapter from WHAT IS LEFT THE DAUGHTER

- Buy the Book

- Read More from Howard Norman

- About the Author

- Connect with HMH