- 314 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The author of

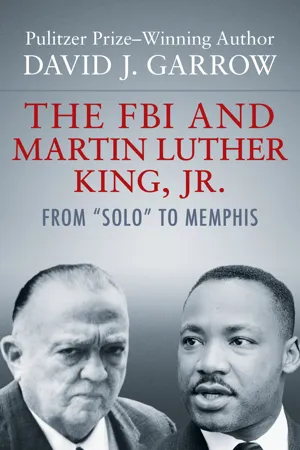

Bearing the Cross, the Pulitzer Prize–winning biography of Martin Luther King Jr., exposes the government's massive surveillance campaign against the civil rights leader

When US attorney general Robert F. Kennedy authorized a wiretap of Martin Luther King Jr.'s phones by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, he set in motion one of the most invasive surveillance operations in American history. Sparked by informant reports of King's alleged involvement with communists, the FBI amassed a trove of information on the civil rights leader. Their findings failed to turn up any evidence of communist influence, but they did expose sensitive aspects of King's personal life that the FBI went on to use in its attempts to mar his public image.

Based on meticulous research into the agency's surveillance records, historian David Garrow illustrates how the FBI followed King's movements throughout the country, bugging his hotel rooms and tapping his phones wherever he went, in an obsessive quest to destroy his growing influence. Garrow uncovers the voyeurism and racism within J. Edgar Hoover's FBI while unmasking Hoover's personal desire to destroy King. The spying only intensified once King publicly denounced the Vietnam War, and the FBI continued to surveil him until his death.

The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr. clearly demonstrates an unprecedented abuse of power by the FBI and the government as a whole.

When US attorney general Robert F. Kennedy authorized a wiretap of Martin Luther King Jr.'s phones by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, he set in motion one of the most invasive surveillance operations in American history. Sparked by informant reports of King's alleged involvement with communists, the FBI amassed a trove of information on the civil rights leader. Their findings failed to turn up any evidence of communist influence, but they did expose sensitive aspects of King's personal life that the FBI went on to use in its attempts to mar his public image.

Based on meticulous research into the agency's surveillance records, historian David Garrow illustrates how the FBI followed King's movements throughout the country, bugging his hotel rooms and tapping his phones wherever he went, in an obsessive quest to destroy his growing influence. Garrow uncovers the voyeurism and racism within J. Edgar Hoover's FBI while unmasking Hoover's personal desire to destroy King. The spying only intensified once King publicly denounced the Vietnam War, and the FBI continued to surveil him until his death.

The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr. clearly demonstrates an unprecedented abuse of power by the FBI and the government as a whole.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr. by David J. Garrow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

“Solo”—The Mystery of Stanley Levison

By May of 1961 Martin Luther King, Jr., had been a man of national stature for over five years. His name had first appeared in the headlines of March, 1956, when the Montgomery bus boycott was three months old. The novelty and courage of that effort made King the leading spokesman for the South’s “new Negro” that he himself often spoke of. He had played prominent roles in the May, 1957, Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, organized to note the third anniversary of the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, and in two other, less heralded Washington demonstrations, the 1958 and 1959 Youth Marches for Integrated Schools. When a deranged black woman stabbed King in a Harlem department store in September, 1958, King again was thrust into the public eye. Two years later, when King was jailed in Georgia on a trumped-up charge of violating parole conditions stemming from a minor traffic conviction, the successful efforts of Democratic presidential nominee John F. Kennedy and his brother Robert to free King were highly publicized.

Despite this notoriety, until May of 1961 the Federal Bureau of Investigation had not taken much notice of King. At that point, King stepped in to take a leading role in the “Freedom Rides” begun by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to desegregate interstate bus transportation facilities across the Deep South. The Director’s office requested information on a number of participants, including King. Bureau officials had little to offer.1

The Mobile, Alabama, field office had compiled a modest amount of information concerning King and the Montgomery bus boycott. Little of it had been forwarded to headquarters, and most of that was filed, without reference to King, under the name of the Montgomery Improvement Association, the organization that had led the boycott.2 The Bureau had been unaware that King and several dozen other southern black ministers had established the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1957 until the bureau’s clipping service came across an article on SCLC in the Pittsburgh Courier nearly seven months later.3 In mid-September, 1957, Bureau headquarters’ supervisor J. G. Kelly forwarded that clipping to the Atlanta field office, where SCLC was based, along with the following instructions:

In the absence of any indication that the Communist Party has attempted, or is attempting, to infiltrate this organization, you should conduct no investigation in this matter. However, in view of the stated purpose of the organization you should remain alert for public source information concerning it in connection with the racial situation.4

Thus, the Atlanta office proceeded to collect routine public information about the SCLC, now one of a number of groups that received such attention. Occasional press clippings about SCLC attempts to organize voter registration drives were routinely noted at Bureau headquarters. In July, 1958, a headquarters’ directive asking for field-office reports on possible “Communist infiltration” of any and all “mass organizations” led Atlanta to summarize its meager file on the SCLC. Atlanta reported “no infiltration known by CP [Communist party] members,” but that SCLC “appears to be [a] target for infiltration.” One Lonnie Cross, allegedly a member of the Socialist Workers party, had sought to work with SCLC in the fall of 1957. Nevertheless, Atlanta agent Al F. Miller concluded, “It is not believed that … [SCLC] warrants active investigation at this time as nature of group’s activities are open and subject to coverage by press. Their prime objective is through public gatherings and meetings to induce Negro qualified citizens to register for voting purposes.”5

In September, 1958, the Bureau’s New York field office opened a file on King when prominent black Communist Benjamin J. Davis, Jr., approached King outside a New York church. Six months later, Bureau headquarters took routine note of a State Department memo announcing an upcoming trip by King to India. In April, 1960, the FBI also noted King’s appearance on “Meet the Press,” and one month later a field office reported that King and black singer Harry Belafonte had met with Benjamin Davis, the black Communist. Late in September, 1960, just after King’s Georgia conviction on a minor driving charge, a low-ranking Bureau headquarters’ official put together a summary of all information the FBI possessed on King. It described the histories of the Montgomery Improvement Association and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, noted King’s reported contacts with Ben Davis, and detailed the assistance that a number of supposed leftists had provided during the Montgomery bus boycott. Nearly forty percent of the seventy-one-page report consisted simply of press clippings on Montgomery or the SCLC.6

The Bureau’s muted interest in King and SCLC continued throughout 1960 and 1961. In October, 1960, the New Orleans field office notified headquarters that one of its informants had attended a three-day SCLC conference in Shreveport. The source reported, “The raising of money appeared to be one of the most important matters at the various meetings.… it appeared the money was all they were after.” Two months later, in December, 1960, U.S. District Judge Irving Kaufman of New York advised the Bureau that both King and the NAACP were supporting the “Committee to Secure Justice for Morton Sobell,” a convicted espionage figure. The information was filed routinely.7

The first high-level Bureau interest in King occurred immediately after publication of an article in the Nation in February, 1961. In it, King made a passing reference to the FBI, calling for the elimination of racial discrimination in federal employment and greater representation of blacks in federal police agencies. Headquarters’ supervisors assigned to monitor just such references reported it to Assistant Director Cartha D. “Deke” DeLoach, adding, “Although King is in error in his comments relating to the FBI, it is believed inadvisable to call his hand on this matter as he obviously would only welcome any controversy or resulting publicity that might ensue.” Two months later, when the State Department notified the Bureau that King was under consideration for membership on its Advisory Council on African Affairs, the FBI responded with a negative evaluation.8

That apparently was all that the Bureau thought it knew about King when the Freedom Rides burst upon the nation in May, 1961. The Director’s office immediately asked for information on King and four other leading figures in the rides. A memo resulted, sent first to Assistant Director Alex Rosen and then to J. Edgar Hoover himself. It stated that “King has not been investigated by the FBI,” and went on to detail the few innocuous contacts King was known to have had with supposedly “subversive” groups and individuals. He had thanked the Socialist Workers party for supporting the Montgomery bus boycott and black Communist Ben Davis, now a member of New York’s city council, for giving blood after his 1958 stabbing. King’s name also had been used in public appeals by the Young Socialist League and by the committee seeking justice for Morton Sobell. It also was said that King had attended meetings of the Progressive party—apparently while an undergraduate at Atlanta’s Morehouse College in 1948—and “in 1957 attended [a] Communist Party training school seminar and reportedly gave [the] closing speech.” Next to the statement that King had not been investigated, Director Hoover wrote, “Why not?” Beside the “training school” allegation he added, “Let me have more details.”9

Regarding the “Communist Party training school,” the author of the memo was repeating a canard that had circulated among right-wingers for over three years. The story stemmed from a speech King had given on September 2, 1957, at the twenty-fifth anniversary celebration of the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee. In attendance that day had been a photographer for a Georgia state segregation commission, Ed Friend. By concealing his identity, Friend had managed to photograph King and others in attendance, including Daily Worker correspondent Abner Berry. Segregationist leaders in Tennessee had been harassing the school for years, since it featured integrated facilities. This 1957 incident was merely one more in a series. Not even the FBI, however, was willing to take this “Communist Party training school” claim seriously. Bureau veterans report that the supervisor who had been so sloppy as to draw Hoover’s interest to this story came to an unhappy end. He was transferred out of headquarters when a more thorough examination showed that the Highlander characterization was clearly erroneous.10

This internal flap may have distracted Bureau supervisors from Hoover’s other question—why King never had been investigated. As the files reveal, and as a Justice Department investigation in 1976 concluded, “FBI personnel did not pursue the King matter at this time. Thus, FBI personnel did not have nor did they assume a personal interest in the activities of Dr. King through May, 1961.”11

Bureau field offices, however, were beginning to pay more attention to the activities of the SCLC. Indeed, SCLC had taken a more energetic role in the burgeoning civil rights movement with the July, 1960, appointment of talented Reverend Wyatt Tee Walker as executive director. A July, 1961, Atlanta field-office report on Walker, written by agent Robert R. Nichols, alleged that Walker subscribed to the Worker, the newly renamed Communist party newspaper. It also said that he and King had taken an active role in seeking clemency for Carl Braden. Braden, convicted of contempt of Congress for refusing to answer questions before the House Un-American Activities Committee, was also once named by a Bureau informant as a Communist party member. No other sources, Nichols reported, knew anything “subversive” or unfavorable about Walker.12

The Bureau’s Memphis office kept headquarters informed of plans for SCLC’s annual convention, to be held in Nashville in late September. This news was furnished by a Nashville pastor associated with SCLC. When the convention ended, Memphis was able to report that its source “knew of no Communist Party (CP) influence at the Conference” and that SCLC had resolved to concentrate on voter registration activities in 1962.13 The Miami office was instructed to look into word that SCLC might organize a door-to-door canvassing effort in that city. Miami reported that no confirmation of the rumor could be obtained.14 In late November, 1961, in line with this innocuous field traffic, Atlanta agent Nichols reported to headquarters, “There is no information on which to base a Security Matter inquiry or Racial Matters investigation of the SCLC at this time.”15

Within barely five weeks of that conclusion, however, Bureau headquarters reported a startling piece of information to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. A January 8, 1962 letter from Director Hoover stated the Bureau had learned that Stanley D. Levison, “a member of the Communist Party, USA.… is allegedly a close advisor to the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.” A reliable informant, Hoover said, had reported on January 4 that Isadore Wofsy, a high-ranking communist leader, had said that Levison had written a major speech that King delivered to the AFL–CIO convention in Miami Beach on December 11, 1961. From all indications, this was the first time that the FBI had realized King and Levison were close friends. In fact, the two men had known each other extremely well for over four years.16

Levison, a white attorney from New York City, had first become involved in the southern civil rights struggle as one of the most active sponsors of a New York group named In Friendship. Organized in 1955 and 1956, In Friendship provided financial assistance to southern blacks who had suffered white retaliation because of their political activity. In Friendship had sponsored a large May, 1956, rally at Madison Square Garden to salute such southern activists, and a good percentage of the funds raised went to King’s Montgomery Improvement Association. Through Bayard Rustin, a black pacifist and civil rights figure who was active in “In Friendship” and who had been the first outside adviser to come and volunteer assistance to King in the early weeks of the Montgomery boycott, Levison was introduced to King in the summer of 1956.17

Levison was eager to be of service to the young and nationally inexperienced leader of the Montgomery protest. His skills lay in exactly those areas where King’s were weak: complicated financial matters, evaluating labor and other liberal leaders who sought to be of assistance, and careful, precise writing about fine points of legal change and social reform programs.18 On this last point Levison’s talents often were combined with Rustin’s. Levison tackled the programmatic sections and Rustin spelled out the detailed analyses of nonviolent direct action. Nowhere was this collaboration and assistance, especially from Levison, of greater help to King than in the drafting and publication of his first book, Stride Toward Freedom,19 an autobiographical portrait centered on the Montgomery protest. Throughout the fall of 1957 Levison shepherded King through the contract negotiations for the book with Harper & Brothers. In early 1958 he turned his attention to the preparation of King’s 1957 income-tax returns.20

By late March, 1958, Levison was carefully reviewing the book manuscript itself, counseling King against including a segment on black self-improvement and urging that he add a section on registration and voting, which King had not touched upon. Levison also told King that the manuscript left an impression that in the Montgomery protest “everything depended on you. This could create unnecessary charges of an ego-centric presentation of the situation and is important to avoid even if it were the fact.” Levison in particular concentrated on the concluding chapter of the book, telling King that it was repetitious and poorly organized. Levison drafted new passages, which were incorporated verbatim into the published text.21

By late summer Levison was informing King of Harper’s promotion plans, and advising that he had been contacted by Civil Rights Commission attorney Harris Wofford. Another contributor to King’s book, Wofford wanted Levison to know that the newly established commission had not received a single voting-discrimination complaint. Levison, as recommended by Wofford, suggested that King find and submit some.22 When King was stabbed at a Harlem department store on September 20 while promoting his new book, it was Levison, accompanied by Rustin, Ella Baker, and Reverend Thomas Kilgore, who met Coretta King at the airport. As King’s recovery proceeded slowly, Levison took charge of administering the flow of contributions that were coming in. He also advised King that SCLC needed to establish a systematic fund-raising mechanism to secure money for a large-scale national program for whenever King chose to launch one. Levison felt King should approach labor leaders such as Walter Reuther for support. He urged, as he had in manuscripts drafted for King, that labor and civil rights join forces to attain their goals.23

King valued the assistance that Levison was giving him on so many fronts. He offered several times to pay Levison for his work and each time Levison strongly refused. “It is out of the question.… My skills,” he explained to King, “were acquired not only in a cloistered academic environment, but also in the commercial jungle.… Although our culture approves, and even honors, these practices, to me they were always abhorrent. Hence, I looked forward to the time when I could use these skills not for myself but for socially constructive ends. The liberation struggle is the most positive and rewarding area of work anyone could experience.”24

Levison’s counsel and assistance, sometimes coupled with Bayard Rustin’s, continued throughout 1959 and 1960. In November, 1959, King asked Levison and Rustin to draft a press release announcing King’s decision to resign as pastor of Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. King wished to move to Atlanta where SCLC’s offices were located, and where he could share a church with his father. Three months later, when the state of Alabama indicted King on baseless charges of income-tax evasion, Levison again stepped into the breach.25 Levison had been disappointed by SCLC’s and King’s relative quiescence in 1958 and 1959, and when the spontaneous college student sit-ins began in Greensboro on February 1, 1960, he welcomed them with special relish. “This,” he wrote to King, “is a new stage in the struggle. It begins at the higher point where Montgomery left off. The students are taking on the strongest state power and demonstrating real will and determination. By their actions they are making the shadow boxing in Congress clear as a farce. They are by contrast exposing the lack of real fight that exists among allegedly friendly congressmen and presidential aspirants. And by example they are demonstrating the bankruptcy of the policy of relying upon courts and legislation to achieve real results.”26

King also came to trust Levison’s judgment regarding SCLC employees. Levison and Rustin had sent Ella Baker to Atlanta to oversee the SCLC office, and King repeatedly enlisted Levison in his attempts to bring Bayard Rustin into a more formal role in the organization.27 Levison and Rustin interviewed Wyatt Walker before Walker was named executive director, and in early 1961 King asked Levison to evaluate a young man who had written seeking advice about a job with the Highlander School’s citizenship education program. King could not recall having met the man—Andrew J. Young. As a result, Young did take a citizenship edu...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Epigraph

- Preface

- 1: “Solo”—The Mystery of Stanley Levison

- 2: Criticism, Communism, and Robert Kennedy

- 3: “They Are Out to Break Me”—The Surveillance of Martin King

- 4: Puritans and Voyeurs—Sullivan, Hoover, and Johnson

- 5: Informant: Jim Harrison and the Road to Memphis

- 6: The Radical Challenge of Martin King

- Afterword: “Reforming” the FBI

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author

- Copyright Page