eBook - ePub

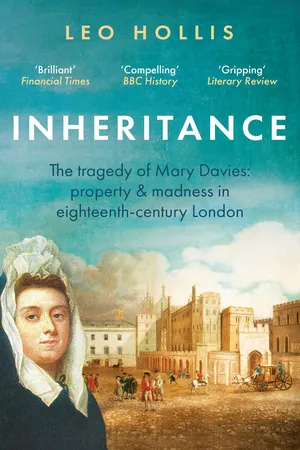

Inheritance: The tragedy of Mary Davies

Property & madness in eighteenth-century London

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

‘Brilliant’ Financial Times

‘Hollis expertly weaves together the human tragedy and high politics behind the explosion of one of the world’s greatest cities’ Dan Snow

The reclaimed history of a woman whose tragic life tells a story of madness, forced marriages and how the super-rich came to own London

June 1701, and a young widow wakes in a Paris hotel to find a man in her bed. Within hours they are married. Yet three weeks later, the bride flees to London and swears that she had never agreed to the wedding. So begins one of the most intriguing stories of madness, tragic passion and the curse of inheritance.

Inheritance charts the forgotten life of Mary Davies and the fate of the land that she inherited as a baby – land that would become the squares, wide streets and elegant homes of Mayfair, Belgravia, Kensington and Pimlico. From child brides and mad heiresses to religious controversy and shady dealing, the drama culminated in a court case that determined not just the state of Mary’s legacy but the future of London itself.

‘Hollis expertly weaves together the human tragedy and high politics behind the explosion of one of the world’s greatest cities’ Dan Snow

The reclaimed history of a woman whose tragic life tells a story of madness, forced marriages and how the super-rich came to own London

June 1701, and a young widow wakes in a Paris hotel to find a man in her bed. Within hours they are married. Yet three weeks later, the bride flees to London and swears that she had never agreed to the wedding. So begins one of the most intriguing stories of madness, tragic passion and the curse of inheritance.

Inheritance charts the forgotten life of Mary Davies and the fate of the land that she inherited as a baby – land that would become the squares, wide streets and elegant homes of Mayfair, Belgravia, Kensington and Pimlico. From child brides and mad heiresses to religious controversy and shady dealing, the drama culminated in a court case that determined not just the state of Mary’s legacy but the future of London itself.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Inheritance: The tragedy of Mary Davies by Leo Hollis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

‘The Way to be Rich’

ON FRIDAY 23 January 1663, following a visit to a coffee house and a discussion on the state of trade with his friend Sir John Cutler, the clerk to the Navy Board, Samuel Pepys, found himself wandering by the Temple Bar, at the western end of Fleet Street. This was the place where, travelling out of the City, the main thoroughfare flowed westward into the Strand towards Westminster. Here, Pepys was at the meeting point where the two tidal currents – the commercial and the courtly – of Restoration London swelled and churned.

To the east, the route rolled downwards to Ludgate and the Fleet River, a slow roiling sewer that disgorged its refuse into the Thames. And, up the other side of the fetid gap, stood the dilapidated hulk of Old St Paul’s Cathedral. This was the City of London, the merchants’ capital. To the west, past the churches of St Dunstan’s and St Clement’s, stood the old aristocratic houses that hugged the Thames along the Strand. They were decidedly down at heel, hard to distinguish from the slums that clustered within the gaps, signs of the disorganised expansion of the city. Beyond, the road followed the curve of the river past the newly established Covent Garden and the open space of the King’s Mews towards Whitehall and Westminster, the centre of the recently revived royal court.

From here Pepys observed urban life in all its variety. This was a place of exchange: along Fleet Street tradesmen, craftsmen and retailers took advantage of the continuous passing traffic to sell their wares, and this main thoroughfare was home to some of the finest purveyors in the capital. Each outlet could be identified by its unique signage, so that the street became a sea of ‘Lions blue and red, falcons, and dragons of all colours, alternated with heads of John the Baptist, flying pigs, and hogs in armour’. Shopping intermingled with fancy, and danger. It was a place for riots and protests, as young people gathered for entertainments and wonders. The playwright Ben Jonson wrote of seeing a performance of ‘a new motion of the city of Nineveh, with Jonas and the whale, at Fleet Bridge’.1 Here also stood St Bride’s Church and Bridewell Gaol to remind the traveller that the distance between salvation and the fall from grace were never far away.

From 1500, when Wynkyn de Worde set up his first press at the sign of the Sun on the south side of the street, this was also home to booksellers and printers that serviced the demands of the educated City elite. It was from one of these booksellers that Pepys picked up, as he later noted, ‘a serious pamphlett and some good things worth my finding’.2 The item was an anonymous thirty-two-page broadside with the full title: ‘The Way to be Rich, according to the practice of the great Audley, who begun with two hundred Pound, in the year 1605, and dyed worth four hundred thousand Pound this instant November 1662, etc.’3

The publication acted as a brief eulogy to Hugh Audley, who had indeed died in November the previous year and, as Pepys noted, had ‘left a very great estate’. Other obituaries noted that he was ‘infinitely rich’. Later historians accepted the definition without scrutiny and Audley became the emblematic image of the early modern moneylender, living alone with his fortune in his rooms in the Temple. Yet Audley could not be reduced to an archetype.

No portraits were painted of this unique Londoner, so the pamphlet that Pepys picked up that January morning will have to suffice. One imagines a man in sober dress, ‘grave and decent’. ‘He wore a Trunk Hose with Drawyers upon all occasions, with a leather Doublet, and plate Buttons; and his special care was to buy good Cloth, Linnen and Woolen, the best being best cheap, and to keep them neat and clean.’4 He avoided taking sides where possible, either religious or political. He was wary of taking high office or becoming too close to the grandees of the city. As he noted: ‘He that eats Cherries with Noble men, shall have his eyes spitted out with the stones.’5 Thus, as he rose, he did not become part of the elite but remained apart, a new class: the so-called ‘masterless men’.

Today, his likeness appears caught between that of the medieval usurer and the protean capitalist. In truth, his life’s work encapsulates the transitions eddying through in the city, as it evolved from a citadel of obligations and hierarchies to a metropolis of speculation. As London lurched fitfully towards becoming the first modern city, Audley became adept at riding the turbulence. His eulogy presents him as a thoroughly modern man: ‘He went on as in a labyrinth with the clue of a resolved mind, which made plaine to him all the rough passages he met with; he with a round and solid mind fashioned his own fate, fixed and unmoveable in the great tumults and stir of business, the hard Rocke in the middest of Waves.’6

Amid such choppy waters emerged the story of Mary Davies’s inheritance.

Audley was born in the heart of the Elizabethan capital, in January 1577, the tenth child of the wealthy merchant, John Audley, and his wife, Margaret. From a young age he was encouraged to learn his letters at the Temple, and was made a lawyer’s clerk. He swiftly proved himself to be a prudent and intelligent student, who learned thrift as well as guile. At this stage of life, his parents may have hoped for a position near to the source of ultimate power, the Crown. To become a councillor was the ideal route for a well-educated citizen, a Thomas Cromwell, giving advice to the monarch, pulling the threads of state, and reaping the profits. However, the queen was not the only master in the city. Money itself was a bright star by which many merchants navigated.

As he learned the law, Audley scrimped every penny where he could, and rather than remain in chambers he became a judicious moneylender. At the time usury was considered a pursuit of ungodly profit, but the negotiations of debt and credit were the grease that lubricated the city’s economy. Banking, as we understand it today, did not yet exist, so all borrowing was on an intimate level and Audley soon gained a reputation as a shrewd but fair creditor. He placed himself close to those who could push business his way, and stepped forward when the right time presented itself. Despite what later historians have claimed, he did not gouge his debtors, but offered a reasonable interest rate of six per cent. However, as his obituary did note, he lived by his wits: ‘his High-way is in By-paths, and he loveth a Cavil, better than an Argument; an Evasion, than an Answer. He had this property of an honest man, That his Word was as good as his Bond; or he could pick the Lock of the strongest Conveyance, or creep out at the Lattice of a word.’7

In time, Audley gathered a fortune of £6,000, but this was just the first act in his accumulation of ‘infinite riches’. Next, he chanced his hand in the Exchange, moving from usury to investments. In the first decades of the emergent English Empire, he put £50 into each of four ships that sailed from the Thames to find new trade. One sank, but the other three returned, and he tripled his ante. After similar successful ventures, once again he needed to diversify his portfolio. Such high-risk speculations demanded to be hedged and Audley then ploughed his surplus into the procurement of lucrative offices, and the safest investment of all – land.

In 1619, he spent £3,000 to purchase the clerkship of the Court of Wards and Liveries, based in the Temple, where he once again took chambers and remained for almost the rest of his life. The Court of Wards was a remnant of a bygone way of the world, a reflection of the feudal obligation of the landowner to his king and a reminder that the Crown was still the final judge on all property.

All property belonged, and still does to this day, to the Crown, obtained through the Norman Conquest. Therefore, property was an idea that originated from, and was imposed from, the top down. This system during the feudal period was structured through the division of the land, and the obligations that went with it. The king gave estates to his barons, who further divided the lands amongst knights, who leased to tenants, and then down to the lowest level of villeins. The donation of land always came with duties going back up the hierarchy: political obedience, military service, a portion of the crops, taxes, rents or mandatory agricultural labour. Thus, the social order of the agrarian economy was regulated and made rigid by the control of access to, and use of, land.

A complex lattice of regulations and customary rights evolved across the centuries. Land moved from one generation to the next by means of primogeniture, the first son taking control of the whole estate on the father’s death. This practice was encouraged, and later enforced by law, to prevent the division of the estate. These feudal rights and customs soon enough became encoded in statutes and contracts. This enshrined in clause and codicil the tension between the king who wished that all property be in his gift, and the landowners who wished to hold on to their property as a legal right.

Initially, common law was encouraged by the Crown as it offered a process that appeared to centralise power, enshrined in the three courts of Exchequer, Common Pleas and the King’s Bench, taking priority over local jurisdictions and manorial traditions. But as the major landowners grew powerful, they too used common law for their own ends. For example, the 1215 Magna Carta was a set of commands to protect the barons’ rights as property holders, in opposition to the Crown.

However, this system was in flux. Slowly, land transformed from the site of customs and obligations, into a legal, and then a commercial, instrument that could be quantified and exchanged. As a consequence, these measurements and transactions needed to be managed, and the professions of lawyers, judges and surveyors, and places of the law, like the Inns of Court, soon blossomed as the proving ground for the new doctrines of private property relations. Most significantly, Parliament emerged as the meeting place for the interests of the emerging landowning classes. In this manner, British law and economy was founded in the adjudication of land disputes and the primacy of property over all other considerations. At the heart of this was the question of the protection of ownership, the mechanics of exchange and the management of inheritance. Often this was in conflict with the interest of the Crown.

But for a market to grow it needs not just a ready demand, the codified rules of exchange, and the offices to oversee it, but also the steady supply of land itself. The 1530s–40s saw the largest exchange of property in British history, that radically transformed the complexion of the nation. It is estimated that in 1531 the Catholic Church owned fifteen per cent of all English land, about twenty per cent of all farmable property. At the time, Henry VIII wanted to break with Rome and was in need of cash to fund his wars. The Dissolution of the Monasteries and the sale of Church lands provided him with a solution to both problems.

This newly acquired land was to be turned to profit. The vast transfer of land heralded a revolution in the law to describe ownership: not for purposes of sufficiency but the production of surplus. Here, English law grew increasingly complex as it sought ways to protect land and empower landowners. This was personified in Parliament itself. And, at the start of this revolution, these tectonic shifts between power, property and privilege set up the inevitable contest between the Crown and the Commons to establish who had power over the regulation of property.

This dispute is illustrated in the strange case of the true mile. In the contest about who had the final say about the laws governing land, measurement became increasingly important. Since the thirteenth century most land was measured by the ‘perch’ or the surveyor’s rod, traditionally marked at 5 1/2 feet. But this only makes sense if the inch itself was also regular. At the time, it was measured by ‘three grains of barley dry and round’. However, Henry VIII decided to reduce the size of the rod by 1/11th, in order to plump up his tax revenue. In response, Parliament refused to comply and maintained the old measurement. This may not have mattered much on a small scale, but when it came to distances like miles, which were also calculated as a multiple of the rod, this created disparities that were to cause serious problems. This dilemma was not cleared up until the 1593 Weights and Measures Act that defined an English mile as 5280 feet. From now on, the measure was to be strictly regulated and policed. Places became defined by their dimensions and boundaries.

Yet there was an alternative system of ownership, in contrast to private property, and one that was regulated from the bottom up: the commons. Common land had traditionally been reserved for the community for their free use. It was often poor soil, but here the poor were able to eke out some kind of subsistence. However, in time, the commons were increasingly deemed unproductive; in the words of Thomas Fuller: ‘the poor man who is monarch of but one enclosed acre will receive more profit from it than from his share of many acres in common with others.’8 And so the commons were enclosed and the poor were driven away. Fences and hedges were raised in order to stop the use of common lands, and despite the powerful history of disputes where boundaries were torn down again, and enclosure challenged, in the end, the interests of private property won, and the fences stayed up.

A good example of this was in the fields close by the Manor of Ebury in Westminster, enclosed in 1592 with ditches and hedges, presumably to be converted into land for livestock, or gardens to produce food for the ever-hungry city. By custom these lands were called Lammas Ground, which is to say that they were commons that anyone could utilise from the day after the harvest, around the begin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 ‘The Way to be Rich’

- 2 ‘Lord, Have Mercy on Our Souls’

- 3 The Preparation of the Bride

- 4 ‘All the Trouble in the World’

- 5 ‘To Such a Mad Intemperance Was the Age Come’

- 6 ‘A Woman of Great Estate’

- 7 ‘Let Him Prove the Marriage’

- 8 ‘One Degree of Madness to Marry a Man Not Worth a Groat’

- 9 ‘For the Good of Her Family’

- 10 ‘An Amazing Scene of New Foundations’

- Afterword

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

- Index

- Copyright