Imperial Powers and Humanitarian Interventions

The Zanzibar Sultanate, Britain, and France in the Indian Ocean, 1862–1905

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Imperial Powers and Humanitarian Interventions

The Zanzibar Sultanate, Britain, and France in the Indian Ocean, 1862–1905

About this book

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Zanzibar Sultanate became the focal point of European imperial and humanitarian policies, most notably Britain, France, and Germany. In fact, the Sultanate was one of the few places in the world where humanitarianism and imperialism met in the most obvious fashion. This crucial encounter was perfectly embodied by the iconic meeting of Dr. Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley in 1871. This book challenges the common presumption that those humanitarian concerns only served to conceal vile colonial interests. It brings the repression of the East African slave trade at sea and the expansion of empires into a new light in comparing French and British archives for the first time.

" Raphaël Cheriau argues that the 'brutal power politics' of recent humanitarian interventions have shaped historians' perspectives on earlier interventions, but that he is able to escape these present-day sensibilities in his approach to British and French interventions in nineteenth-century eastern Africa. While I might challenge that suggestion, nonetheless he offers historians a valuable book that explores in detail the way imperialists of the nineteenth century did and did not use humanitarianism as a justification for their work in eastern Africa." - Elisabeth MacMahon, The English Historical Review

" The author weaves together a rich trove of primary documents from both British and French archives; some of these have been fruitfully exploited by previous historians, others reflect Cheriau's energetic digging to go beyond the obvious. He also draws upon an equally dense corpus of published primary sources in both languages, as well as several contemporary newspapers, while his mastery of the secondary literature is impressive." - Edward Alpers, Australian Institute of International Affairs

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part I

The right of visit, the French flag, and the repression of the slave trade in Zanzibar

1The repression of the slave trade

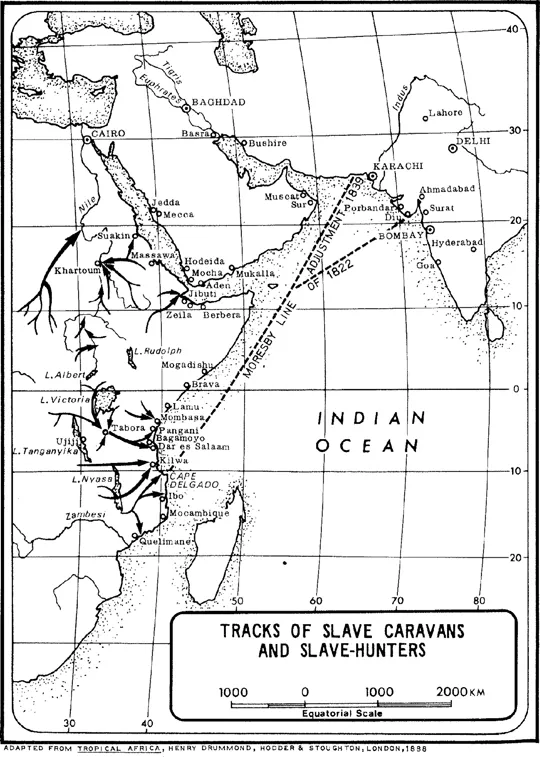

1.1Zanzibar dhows and the elusive Indian Ocean slave trade

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of maps

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- A note on translations

- Introduction: Zanzibar or the dramatic encounter of imperialism and humanitarianism

- PART I The right of visit, the French flag, and the repression of the slave trade in Zanzibar

- PART II Empire and humanitarian action in Zanzibar: A troublesome relationship

- PART III Zanzibar’s contribution to international law and humanitarian operations

- Conclusion: abolitionism and humanitarian intervention; ‘ugly business behind great words’?

- Select bibliography

- Index