- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Defining the Chief Executive via flash powder and selfie sticks

Lincoln's somber portraits. Lyndon Johnson's swearing in. George W. Bush's reaction to learning about the 9/11 attacks. Photography plays an indelible role in how we remember and define American presidents. Throughout history, presidents have actively participated in all aspects of photography, not only by sitting for photos but by taking and consuming them. Cara A. Finnegan ventures from a newly-discovered daguerreotype of John Quincy Adams to Barack Obama's selfies to tell the stories of how presidents have participated in the medium's transformative moments. As she shows, technological developments not only changed photography, but introduced new visual values that influence how we judge an image. At the same time, presidential photographs—as representations of leaders who symbolized the nation—sparked public debate on these values and their implications.

Lincoln's somber portraits. Lyndon Johnson's swearing in. George W. Bush's reaction to learning about the 9/11 attacks. Photography plays an indelible role in how we remember and define American presidents. Throughout history, presidents have actively participated in all aspects of photography, not only by sitting for photos but by taking and consuming them. Cara A. Finnegan ventures from a newly-discovered daguerreotype of John Quincy Adams to Barack Obama's selfies to tell the stories of how presidents have participated in the medium's transformative moments. As she shows, technological developments not only changed photography, but introduced new visual values that influence how we judge an image. At the same time, presidential photographs—as representations of leaders who symbolized the nation—sparked public debate on these values and their implications.

An original journey through political history, Photographic Presidents reveals the intertwined evolution of an American institution and a medium that continues to define it.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Photographic Presidents by Cara A. Finnegan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Histoire de la photographie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

The Daguerreotype Presidents

CHAPTER 1

Photographing George Washington

In February 1839 the Boston Daily Advertiser published news from France of a “curious invention lately made by M. Daguerre; for making drawings.” The writer noted that while “the manner in which the camera obscura produces images of objects, by means of a lens, is well known,” Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre’s contribution was “a method of fixing the image permanently” that did so “by the agency of the light alone.” The article went on to explain that Daguerre’s “machine” could make “accurate drawings” of “any object indeed, or any natural appearance may be copied by it.” One man who had observed Daguerre’s efforts compared the new technology “to a kind of physical retina as sensible as the retina of the eye.”1

As the Daily Advertiser’s choice to publicize Daguerre’s efforts illustrates, Americans were keenly interested in the idea of photography. Some enthusiasts in the late 1830s were experimenting with “photogenic drawing,” the process of exposing objects to light-sensitive paper pioneered by William Henry Fox Talbot in England.2 But it was Daguerre’s invention that most captured the American imagination. In 1839 a few Americans who had read about Daguerre’s experiments before the entire process was made available to the public tried to make the images but without documented success.3 Famed inventor Samuel Morse experimented with proto-photographic processes for years, visited France to promote his own invention of the telegraph, and met Daguerre in early 1839.4 Months before the French officially presented the daguerreotype to the public, Morse wrote a letter about the process to his brothers, who circulated it to U.S. newspapers. In it, he called Daguerre’s invention “Rembrandt perfected.”5

After the French government formally presented the daguerreotype to the public in August 1839, copies of European newspapers describing how to perform the new process made their way across the Atlantic to the United States.6 Once on American shores, the daguerreotype quickly became an open-source, commercially viable technology. For his part, Morse publicized and supported Daguerre’s new invention in the United States while at the same time downplaying the simultaneous photographic discoveries of Talbot in England.7 The daguerreotype quickly took off in the United States, eclipsing other nascent modes of photography.

A daguerreotype is a one-of-a-kind, fixed photographic image made by the action of light upon a plate sensitized by chemical solutions. According to photo process historian Mark Osterman, a copper plate is coated with light-sensitive silver, the plate is exposed in the camera, and then the hidden image is revealed “by allowing the fumes of heated mercury to play upon the silver.” The daguerreotype is then washed in a fixing solution to make the image permanent and, finally, “toned with a solution containing gold chloride.”8 The resulting image, which could come in a variety of sizes depending on the plate used, is a “highly polished silver mirror” that, when manipulated by the hand, alternately reveals the highlights and shadows of its fixed image.9

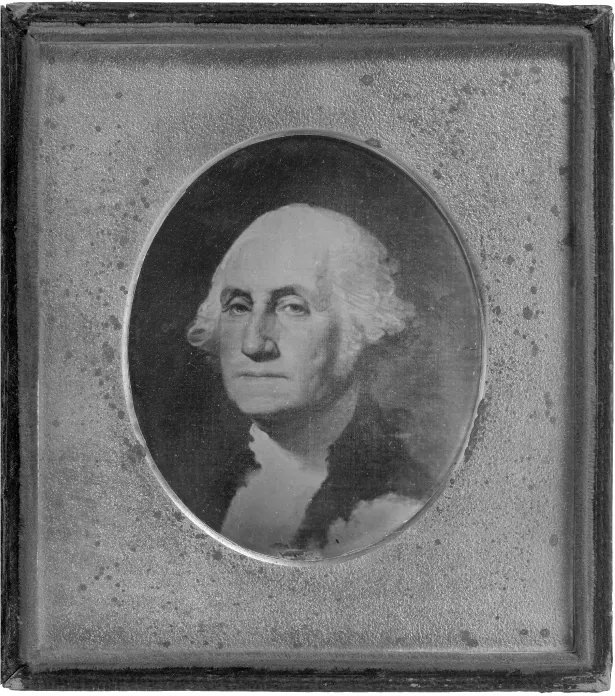

Almost as soon as Americans started making daguerreotypes, they made daguerreotypes of George Washington. The fact that he was unavailable to be photographed from life was no obstacle. Though he died in 1799—a full forty years before photography’s invention—the nation’s first president nevertheless appeared as a subject in daguerreotypes of busts, painted portraits, and prints, ironically making daguerreotypes of Washington’s image some of the earliest presidential photographs. Take, for example, a daguerreotype of Gilbert Stuart’s famous, yet unfinished, 1796 “Athenaeum” portrait of George Washington. Roughly three inches tall by two and a half inches wide and easily held in one hand, the lightly tarnished, quarter-plate daguerreotype of Washington is preserved behind glass and a gilded mat, cushioned by red velvet, and protected by a worn wooden and leather hinged case. But its mirrored surface still clearly offers up Washington’s painted gaze, one that is familiar to us today in large part because we carry it in our wallets on the U.S. dollar bill.

Figure 1.1: John Adams Whipple, daguerreotype of portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart, 1847. (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Helen Hill Miller.)

When the case is opened, a message appears opposite the Washington image. In embossed letters on a red velvet background, a tiny brass plate reads:

DAGUERREOTYPED BY

JOHN A. WHIPPLE

NOV. 15TH 1847.

JOHN A. WHIPPLE

NOV. 15TH 1847.

The daguerreotype and its tiny brass plate invite several questions. What, precisely, has been “daguerreotyped” here? At first glance, the answer would seem simple: Whipple has made a daguerreotype of a famous painting of George Washington. But why? To share Stuart’s famous portrait with others who might not otherwise see it? As an experiment or practice for a photographer continually honing his craft? To illustrate to potential customers Whipple’s own prowess in the art of the daguerreotype? To tap into (and perhaps profit from) mid-nineteenth-century Americans’ obsession with the iconic founder? Or perhaps the choice of Stuart’s Athenaeum portrait was one of mere convenience; the portrait got its name because it was held in Boston’s Athenaeum, the local library, so it theoretically would have been accessible to the photographer.10 There are no definitive answers to these questions. Nevertheless, the practice of photographing George Washington offers a helpful point of entry into this book’s exploration of how presidents have helped to shape photography across its history. Because it turns out that once Americans got photography, they needed a photographic George Washington.

Whipple’s Washington

John Adams Whipple worked as a photographer in Boston starting in the 1840s, and by the 1850s he was a well-known and well-regarded practitioner. Whipple grew up with an interest in chemistry and came to photography while working as a supplier of photographic chemicals in Boston.11 By the late 1840s Whipple ran a studio with his partner, James Black, where he participated in most aspects of the photographic trade. The 1848–1849 Boston Directory listed him as one of twenty-two sellers and producers of “Daguerreotype Miniatures” in the city.12 An ad in that same publication advertised “Whipple’s Daguerreotypes—BY STEAM,” noting that Whipple had successfully integrated steam power into the production of his images, enabling him to “furnish my customers with BETTER MINIATURES IN LESS TIME THAN FORMERLY, ESPECIALLY BEAUTIFUL LIKENESSES OF LITTLE CHILDREN, Which I will warrant to make satisfactory to parents, If they will call upon me between the hours of 11 and 2, when the sky is clear.”13 For an art of “sun-painting” that relied on the exposure of its subject to a light-sensitive medium, a clear sky was essential.

Today Whipple is remembered for his contributions to the science of photography and the photography of science. For example, in 1850 Whipple and Black patented a process for making paper prints from glass negatives—what they called “crystalotypes”—which opened the door to the printing of photographs on paper in later decades.14 During this period Whipple also experimented with photographing the moon and stars using a large telescope at the Harvard College Observatory. After several failures over the span of three or so years, he finally succeeded in making a spectacular daguerreotype of the moon in 1851.15

Closer to the subject of his Washington daguerreotype, Whipple also showed interest in the photography of art and in images related to the nation’s founders.16 In what may have been one of his early experiments with the crystalotype, Whipple made and printed on paper a vibrant image of a classically themed statue of a male and female pair walking together.17 Later, in 1854, Whipple contributed images to a book called Homes of American Statesmen, a nearly five-hundred-page compendium of patriotic biographies of the nation’s founders. Such publications were common during this period. Merry Foresta writes, “In America the nineteenth century was a great period of taking stock, of retrospection and recovery as well as expansion, and photography was considered the truest agent for listing, knowing, and possessing, as it were, the significance of events.”18 Each statesman’s profile was accompanied by facsimiles of his letters and engravings of his home, many of which originated as daguerreotypes. The George Washington chapter featured an engraving of a Cambridge, Massachusetts, house that Washington lived in during the Revolution, based upon a daguerreotype by Whipple.19 Each book was sold with a photographic frontispiece of John Hancock’s Boston home by Whipple; printed directly on paper, the image was, according to a publisher’s note in the book, “somewhat of a curiosity, each copy being an original sun-picture on paper.”20 The frontispiece constituted perhaps one of the earliest examples of a photograph being printed in or with a book.

The daguerreotype of the Washington painting was thus far from unusual for its creator. In many ways it embodied what we know of Whipple’s overarching interest in the art and science of photography and his commitments to technical and aesthetic experimentation with the photography of art objects. Perhaps his choice to photograph Washington was also tied to a patriotic and commercial investment in telling visual narratives of the nation’s founders. If so, Whipple was not alone.

George Washington as Visual Icon of the Nation

For nearly all of the nineteenth century, George Washington was the visual icon of the nation, its metaphorical father figure and shaper of national character. This status emerged during Washington’s own life as he took command of the Continental forces during the Revolution and then later assumed the presidency. Publicly circulated visual images played a central role in the emerging iconicity of Washington. The culture more broadly was interested in new topics for visual representation, as the later eighteenth century brought with it a shift from public interest in portraits of religious figures to more secular figures such as soldiers and politicians.21 In the case of George Washington, those new images came in a dizzying variety of forms, everything from pictures in books and magazines to prints suitable for framing and even sheet music. Writes Wendy Wick Reaves, “Never before in America had a single subject produced such a quantity of visual material over an extended period of time.”22 Many images came with Washington’s explicit cooperation. For if Washington in his Cincinnatus guise was a famously reluctant general and later a reluctant president, he does not appear to have been reluctant to pose for portraits or busts.23 His fame and his own interest in visual representation led the most famous artists of the day to seek him out. Washington sat for upward of twenty-eight portrait painters, some more than once.24 When the images were completed, many of them stayed in the Washingtons’ possession. Furthermore, the president displayed images of himself in his home at Mount Vernon and was known to proudly show them off to visitors.25

In life, and as captured by some of the finest painters and sculptors of the day, Washington’s body was already understood to be a national body that embodied American values.26 Washington’s status as a visual icon only grew after his death. Barry Schwartz writes that between 1800 and 1860, “American writers produced at least 400 books, essays, and articles on Washington’s life. During this time, Washington’s image was not that of a mere celebrity, it was sacred.”27 Dramatic illustrated prints such as John James Barralet’s 1802 Apotheosis of Washington, which featured Washington being elevated to divine status by allegorical figures representing Father Time and Immortality, used familiar iconology to confirm and perform that sacred status.28 Later the 1820s and 1830s brought the rise of the illustrated celebrity biography, followed around 1840 by the first illustrated history books chronicling the founding of the nation.29 Not surprisingly, Washington’s image repeatedly circulated in these contexts.30 By the 1840s, when photography was just appearing on the national scene, the profusion of images of Washington continued, even including his likeness on household wares like textiles and buttons. Yet despite the diversity of places where one could find images of Washington circulating, the images themselves did not differ all that much from one another.31 The source image...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I. The Daguerreotype Presidents

- Part II. The Snapshot President

- Part III. The Candid Camera Presidents

- Part IV. The Social Media President

- Conclusion: The Portrait Makes Our President

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- Back Cover