eBook - ePub

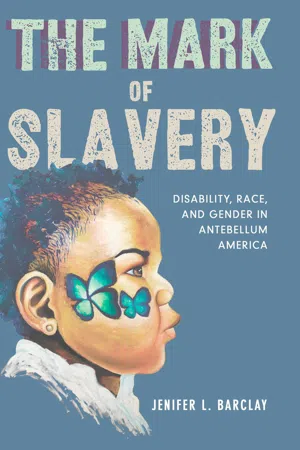

The Mark of Slavery

Disability, Race, and Gender in Antebellum America

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Exploring the disability history of slavery

Time and again, antebellum Americans justified slavery and white supremacy by linking blackness to disability, defectiveness, and dependency. Jenifer L. Barclay examines the ubiquitous narratives that depicted black people with disabilities as pitiable, monstrous, or comical, narratives used not only to defend slavery but argue against it. As she shows, this relationship between ableism and racism impacted racial identities during the antebellum period and played an overlooked role in shaping American history afterward. Barclay also illuminates the everyday lives of the ten percent of enslaved people who lived with disabilities. Devalued by slaveholders as unsound and therefore worthless, these individuals nonetheless carved out an unusual autonomy. Their roles as caregivers, healers, and keepers of memory made them esteemed within their own communities and celebrated figures in song and folklore.

Time and again, antebellum Americans justified slavery and white supremacy by linking blackness to disability, defectiveness, and dependency. Jenifer L. Barclay examines the ubiquitous narratives that depicted black people with disabilities as pitiable, monstrous, or comical, narratives used not only to defend slavery but argue against it. As she shows, this relationship between ableism and racism impacted racial identities during the antebellum period and played an overlooked role in shaping American history afterward. Barclay also illuminates the everyday lives of the ten percent of enslaved people who lived with disabilities. Devalued by slaveholders as unsound and therefore worthless, these individuals nonetheless carved out an unusual autonomy. Their roles as caregivers, healers, and keepers of memory made them esteemed within their own communities and celebrated figures in song and folklore.

Prescient in its analysis and rich in detail, The Mark of Slavery is a powerful addition to the intertwined histories of disability, slavery, and race.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Mark of Slavery by Jenifer L. Barclay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Illinois PressYear

2021Print ISBN

9780252085703, 9780252043727eBook ISBN

97802520526131 Disability, Embodiment, and Slavery in the Old South

In a mid-1930s interview, former slave Henry Gladney reminisced about his childhood on a South Carolina plantation near White Oak. He especially remembered the fierce bond between his parents, Bill and Lucy. “Pappy,” Gladney recalled, “didn’t ’low other slave men to look at my mammy.” His uncle once transgressed this rule and Gladney watched his father, known as Bill de Giant because of his size and strength, “grab Uncle Phil … [and] throw him down on de floor.” “When him quit stompin’ Uncle Phil,” Gladney explained, “they have to send for Dr. Newton ’cause Pappy done broke Uncle Phil’s right leg.” John Mobley, who enslaved Gladney and his kin, didn’t “lak day way one of his slaves was crippled up” and threatened to whip Bill for injuring Phil. Lucy intervened and “beg for pappy so,” saying that Bill would run to the North if Mobley punished him. In the end, “nothin’ was done about it” because Mobley feared that if he punished Bill, he would “lose a good blacksmith wid two good legs, just ’bout a small nigger man wid one good leg and one bad leg.”1

This tale illustrates that many factors had a bearing on the disabling injury Phil experienced, even as it erases his lived, embodied experience of mobility impairment in the aftermath of this family conflict. In the context of the mid-nineteenth century, a broken limb was a serious, sometimes life-threatening injury that could easily lead to permanent physical impairment given the lack of centralized care, antibiotics, effective anesthesia, precise surgical techniques, and sterile environments that characterized antebellum medicine. These realities, though, arguably faced anyone treated by regular, professional physicians at the time. Phil’s circumstances—his “bad leg” that left him “crippled up” and the fact that his owner perceived him as a “small” man with no discernible labor skills—had even greater implications because he was enslaved.

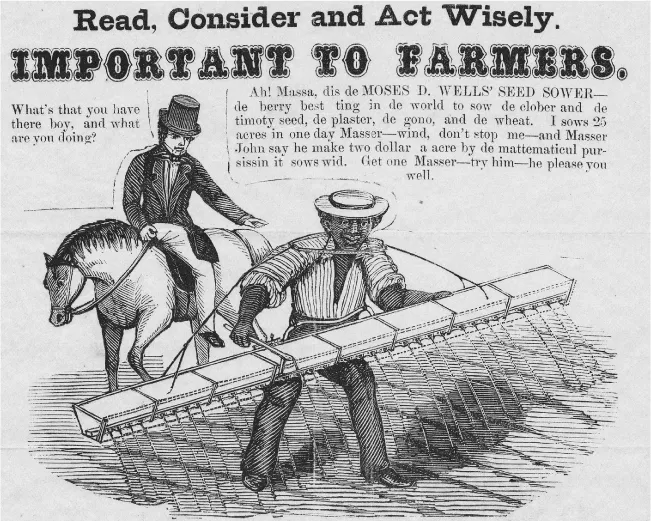

Under a system in which the body was routinely categorized and valued based on size, strength, physical ability, mental acuity, and skill, Phil possessed few attributes that made him valuable to slaveholders. His disabling injury—which stood in contrast to the large, robust, blacksmithing body of his brother Bill de Giant—magnified Phil’s perceived limitations as a laborer. Slaveholders had an overwhelming interest in bondpeople’s soundness, a socially, legally, and medically created concept that measured the presumed usefulness of their bodies and minds and, when paired with the “hand system,” gauged their capacity to labor.2 Through the purely economic lens of racial chattel slavery, enslaved people were valuable property, laborers, and (for women) reproducers of future generations. All of these elements created and perpetuated the wealth of the planter class, but only if slaves’ bodies, minds, and wombs remained sound. Individuals’ personalities or status within their families and communities mattered little in this scheme. Above all else, slaveholders valued healthy, powerful, and productive bodies and slaves with just enough intellect to agreeably and capably optimize slaveholder profits (see fig. 1).

This hegemony of sound bodies and minds, on such clear display in Gladney’s tale about his Uncle Phil and in the Wells’ seed sower advertisement, pervades historical sources as well as most scholarship about slavery. As a labor system, slavery depended on sound, strong slave bodies to toil endlessly in agrarian, urban, and even emerging industrial spaces in the Old South. Slave bodies abound in this history since they were sites of production and reproduction as well as a peculiar form of thinking, feeling property to be bought and sold at will. Slaves’ bodies and minds were also sites of suffering, sickness, and abuse as antislavery advocates highlighted in the nineteenth century and as scholars have emphasized since. Slaves’ bodies also figured prominently in resistance: they ran away and “stole themselves”; women resisted pregnancy through abstinence, birth control, and abortifacients, using their bodies to engage in gynecological resistance; and some slaves cleaved out a metaphorical “third body” as a site to experience pleasure through dance, clothing, adornment, and other means.3 Even today, Americans “embody” slavery vicariously through books, films, exhibitions, and reenactments to locate themselves in the past and imagine what they would do in this context.4 Yet despite the important role that the body played in slavery, in arguments against it, in scholarship about it, and even in how it is remembered, the corporeality and lived experiences of those with unsound bodies under slavery—bodies today considered “disabled”—are uncomfortably passed over with only a few exceptions.5

Figure 1. “Moses D. Wells’ Seed Sower” (ca. 1850s). This advertisement illustrates the quintessential physical attributes that slaveholders highly esteemed among the people they enslaved. Note this enslaved man’s broad shoulders, powerful arms, and muscular legs—necessary for lugging heavy equipment that would maximize slaveholder profit—in comparison to the finer, more delicate embodied characteristics of his mounted “masser.” The imagined dialogue between the slave and master further emphasizes the profit to be made from an able-bodied man’s use of this particular piece of equipment: “I sows 25 acres in one day, Masser[!]” The original advertisement has been cropped here to focus on the illustration. Image courtesy of the Virginia Museum of History & Culture, Broadside Collection.

The institution of slavery produced unsound, impaired bodies through which enslaved people experienced their daily lives. Overwork, abuse, punishment, insufficient material resources, dangerous working environments, and poor living spaces are among just a few conditions that took a profound toll on slaves’ bodies. For some, congenital physical and sensory conditions shaped their experiences of enslavement from the moment of their birth, while for others impairment came with age. For others yet, madness, “mental alienation,” and “fits”—impairments also intimately bound up with the body—wove in and out of their daily lives.6 The array of conditions that produced “unsoundness” among enslaved people epitomize and add new dimensions to the notion of “complex embodiment.” They show that disabling environments produced disability and affected “people’s lived experience of the body” while simultaneously acknowledging that “some factors affecting disability, such as chronic pain, secondary health effects, and aging, derive[d] from the body.”7 For some enslaved people, the disabling conditions they experienced derived from their bodies and deeply affected their lived experiences under slavery, while for others the conditions of slavery impaired their bodies and gave rise to new and sometimes chronic experiences of disability.

While it is difficult, perhaps even impossible, to say precisely how many enslaved people lived and worked with various forms of impairment on southern plantations, one estimate suggests that about 9 percent of enslaved people experienced some type of physical, sensory, psychological, neurological, or developmental condition.8 Based on that estimate, anywhere from 360,000 to 540,000 of the 4 to 6 million people in bondage on the eve of emancipation experienced missing or misshapen limbs, deafness, blindness, congenital anomalies, epilepsy, insanity, debilitating diseases, and a host of other apparent and nonapparent conditions. Ignoring the presence of these conditions in enslaved people’s lives casts all historical actors as nondisabled and imagines the “universal” slave experience as one that unfolded in an unchanging, fully functional body with mental acuity and awareness fully intact. Impaired bodies, however, are lived bodies and since all bodies are “the stuff of human affliction and affectivity as well as the subject/object of oppression,” they deserve our attention in the deeply oppressive context of racial slavery in the United States.9

Unsoundness in Infancy and Childhood

One of slaveholders’ main concerns was the perpetuation of their labor force through “natural increase”—the birth of healthy, sound enslaved children. This was particularly important in North America after the U.S. Constitution banned the transatlantic slave trade in 1808 (though it continued illegally) and restricted slave trading to domestic inter- and intrastate routes.10 Enslaved women’s reproductive capacity was crucial to the maintenance of slavery, so much so that slaveholders measured the potential wealth of children they were likely to produce. This sentiment was embedded in the idea of “future increase,” a term routinely used in wills, bills of sale, and other legal documents that referred to the potential number of children a woman seemed likely to bear in her lifetime and their estimated value.11 Future increase banked on the health and soundness of these commodified future children and their mothers’ fecundity. Even enslaved people acknowledged the importance of sound, healthy infants to slaveholders and the horrifying measures they sometimes took to stack the deck in their favor. One formerly enslaved woman explained that slaveholders “ain’t let no little runty nigger have no chilluns. Naw sir, dey ain’t, dey operate on dem lak dey does de male hog so’s dat dey can’t have no little runty chilluns.”12 Despite such attempts to guarantee the birth of only sound babies, slaveholders’ hopes for the soundness of bondwomen’s “future increase” were not always met.

Many children were born under slavery with congenital conditions that resulted from genetics or prenatal factors like poor maternal diet, overwork, or disease. One of the most common involved varying degrees of sightlessness. On Dr. Mazyck’s Santee River plantation in South Carolina, one enslaved girl was born with no eyes. She became the object of local physicians’ scrutiny and was categorized as “defective” in comparison to her otherwise “remarkably fine and healthy family.” By the time she was nine years old, her empty eye sockets caused her forehead to take on “a contracted character.” Because of her blindness and disfigurement, her owner estimated her to be of little value even though she likely undertook labor such as needlework and contributed to household chores.13

Blindness also shaped the life of an unnamed child born on a Virginia plantation with congenital cataracts. Neither of his eyes “fixed upon objects” and over time “acquired a constant vibratory motion.” In 1854 or 1855, at eleven years of age, he underwent an operation at Bellevue Hospital in Richmond, Virginia. Here, physician Thomas Pollard removed the cataracts, bandaged this young boy’s eyes, and “confined [him] to a darkened room” for ten days. Four weeks later, Pollard noted that the child’s eyes were “clear and healthy” but that “the vibratory motion … continues.” In the end, Pollard declared that the boy’s retinas were “paralyzed” and explained that for the remainder of his life he would only see vague movements of large objects in shades of black, white, gray, and red.14 For both of these children, their congenital blindness combined with their status as slaves, rendering them damaged and inferior to slaveholding whites. Their owners devalued them, perceiving them as useless and unsound property. Physicians, on the other hand, looked at them as medical curiosities and problems, methodically recorded facts and observations about their conditions, and sometimes performed surgeries to “correct” their impairments and restore their worth.

Slaveholders expressed varying degrees of concern or indifference for enslaved children who were born with or developed eye problems. Since enslaved people had no say in the matter, some slaveholders sought medical intervention to restore children’s vision, which included rudimentary and painful surgeries. Despite seeking out these measures, slaveholders’ labor demands sometimes deprived children the opportunity to recover fully from such procedures. As one physician explained, he surgically removed congenital cataracts from the eyes of an otherwise healthy sixteen-year-old girl and expected her totally to regain her sight. Before her eyes healed, though, “her master, at about the close of four weeks, set her to work in the field, in the month of June … which induced such a degree of inflammation as well-nigh destroyed her eye.”15 This young bondwoman’s labor was more important than her recovery for her owner, whose indifference caused her to lose sight in one eye. Other slaveholders reacted to the looming prospect of blindness for those they enslaved with more concern. Some aggressively sought medical intervention in the hopes of avoiding the depreciation of their property. In 1839, Virginia planter Thomas W. Epes beseeched Dr. John Peter Mettauer to examine and perhaps operate on “a little girl” who lost one eye at six months of age “no doubt in the same way this one is [now] affected.”16 Clearly seeking to preempt total blindness, Epes took a far more proactive approach to this enslaved child’s condition. His intentions, however, had little to do with her interests and more to do with preserving the value of his property and her future labor potential.

Some enslaved infants were born with physical differences that diminished their value as slaves and created circumstances unique to them and their families. These conditions included “clubbed” feet and “harelips,” imperfectly formed or missing limbs, and the rarer phenomenon of conjoined twins. By the mid-nineteenth century, physicians sought to “correct” many of these conditions through orthopedic surgical techniques; some, however, remained mysteries categorized as “monstrosities.” Physicians and slaveholders alike viewed enslaved children considered monstrous as curiosities and treated them with troubling degrees of aloofness and disgust. The devaluation of disabled black bodies under slavery combined with physicians’ clinical detachment and desire to “fix” congenital disabilities produced emotional distress, additional labor, and other challenging circumstances for enslaved children with congenital disabilities and their loved ones.

As with children who experienced forms of congenital blindness, some physicians used developing orthopedic surgical techniques to “correct” congenital physical conditions that compromised enslaved children’s future labor potential. In 1854, Dr. Thweatt of Petersburg, Virginia, operated on a six- to eight-month-old enslaved infant “with deformity of both feet.” He performed the procedure with no anesthesia and noted that “the child apparently did not feel the operation.” For many months caregivers administered anodyne, strong pain relievers, when the enslaved infant was “restless” and attached “small splints” and other devices to his legs to “retain the feet in their proper direction.” Thweatt visited the child periodically to check the progress of his recovery, but he did not mention who provided the extra care, changed bandages, kept incision sites clean, adjusted the braces, splints, and other hardware, administered medications, and nurtured the infant through painful or uncomfortable phases of treatment. He concluded only that “under this treatment the deformity almost entirely disappeared.”17 Eliminating the prospect of a crippled bondman undoubtedly pleased this child’s owner, and his parents were likely overjoyed at his recovery from this terrible, painful ordeal. Antebellum physicians also developed surgical procedures to correct “harelip,” though none performed this procedure on enslaved infants or children because they perceived it as cosmetic.18

In addition to congenital vision and physical impairments, more rare conditions sometimes occurred among enslaved infants like conjoined twins. Long met with wonder and astonishment and frequently described as “monstrosities,” many twins fused together in utero died at birth, but some occasionally survived. Millie and Christine McKoy, the children of Monemia and Jacob born on Jabez McKay’s North Carolina plantation in July 1851, were one such exceptional case. Joined near the pelvis, Millie and Christine survived infancy, lived to be sixty-one years of age (dying only hours apart), and experienced a highly unusual life compared to most enslaved people. John C. Pervis bought the twins in 1852 for a thousand dollars when their owner tired of the constant stream of neighbors, doctors, and other visi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Disability, Embodiment, and Slavery in the Old South

- 2. Reimagined Communities: Disability and the Making of Slave Families, Communities, and Culture

- 3. A Dose of Law: The Dialogics of Race and Disability in Southern Slave Law and Medicine

- 4. “Cannibals All!” The Politics of Slavery, Ableism, and White Supremacy

- 5. “One Hell of a Metaphor”: Disability and Race on the Antebellum Stage

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Back Cover