- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

100 Posters That Changed The World

About this book

Classic posters from the last 300 years and the stories behind them.

Posters have always been designed to seek an immediate response. From the time when paper was first affordable, the poster has been used to provoke a direct reaction, whether a public appeal, a legal threat, a call to arms, or the offer of entertainment. Newspapers might have the advantage of ubiquity in spreading

the word, but a poster could be tightly targeted by its location.

Organized chronologically, 100 Posters That Changed the World

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 May Celebrations

(1936–1977)

The roots of May Day celebrations lie in pre-Christian rites to welcome the return of fertile Spring. However, over the course of the twentieth century, the sounds of revelry have sometimes had to compete with the din of May Day demonstrations and, often, their counter-demonstrations.

As far back as Roman times, people would celebrate the arrival of spring in May with dancing, banquets and devotional rites. In the industrial age, when the rights of labour were being given serious consideration, 1 May took on a new role as International Workers’ Day, established by trade unions. Traditional festive May Day parades became marches for improved conditions and pay; thus a 1955 poster for the Confederation of German Trade Unions by Paul Reiff shows a small child beaming with delight as he realizes that “on Saturdays my daddy is mine”.

The Soviet Union, which used posters extensively as its channel of ideological communication, always made great play of International Workers’ Day. Alexei Kokorekin’s 1945 poster shows the Soviet flag flying proudly among the blossom. “1 May greetings to heroes of frontline and back areas,” says the strap line. During World War II, Kokorekin’s posters tended to be rather more aggressive in tone with square-jawed Russian soldiers and sailors bayoneting Nazis or hurling grenades. The blossom poster suggests that after the terrible sacrifices of Russia’s Great Patriotic War, the nation can now look forward to a peaceful future.

Harmony is also the central theme of Viktor Koretsky’s poster showing various people of the world striding forward under banners which read “Peace” in many languages, including German. Naturally, Koretsky depicts Russia as leading the way in the march towards global friendship. Regrettably, such sentiments were in short supply when the poster came out in 1956, the year that Israel invaded Egypt and the Soviet Union invaded Hungary.

Not every May Day event had such noble objectives. The event has often been hijacked for propaganda and politicized in ways which would horrify those who first proposed it. In countries where the divide between differing political views is stark, May Day is often more notable for the smell of tear gas than May blossoms. The May Day poster by Gülgün Basarır shows a clenched fist holding a spanner filled with the faces of Turkish workers. It was designed in 1977 when a May Day demonstration in Istanbul’s Taksim Square ended in bloodshed after an unidentified gunman opened fire on the crowd. At least thirty-four people died and the Turkish government banned May Day rallies in the square for the next thirty years. More recent May Day events in the city, when they have been permitted, have also been flashpoints for conflict.

A quartet of 1 May celebration posters. The Soviet poster with May blossom (top left) was an unusual subject for Alexei Kokorekin who produced many propaganda posters in World War II. He was a two-time winner of the Stalin Prize, but died in the smallpox outbreak of 1960, after returning from India with the disease.

WPA: Social Policy Posters

(1936–1943)

The economic and social wreckage wrought by the Great Depression in the US gave rise to a short-lived, nationwide regeneration project of breathtaking ambition and scope, unique outside totalitarian regimes. Poster art was at the very heart of this great experiment.

When Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected President of the United States in 1933, he took the helm of a country in the grip of the Great Depression, soon compounded by a cruel drought which destroyed the agricultural heartland of the country. Roosevelt introduced radical emergency measures in 1935 to restructure and stimulate the economy, including reform and regulation of the banking and securities sectors, and the federal control of agriculture production.

Dubbed the New Deal, this large-scale government intervention in the economic and industrial activities of the nation included the ambitious Works Progress Administration (WPA), which undertook major state-funded infrastructure, social and cultural projects, as a means of reducing unemployment. By the time the WPA was disbanded in 1943 it had employed 8.5 million people.

To characterize the WPA solely as a road-building and housing programme is to underestimate its nation-building ambitions. Its choice of projects reflected wider social and cultural aims as a means of addressing the social damage and threatened unrest caused by the Great Depression. Projects were chosen for their contribution to the creation of a more equitable and cohesive society, effectively reimagining America for a new age, in the hope of avoiding a disaster such as the Great Depression in the future.

Emblematic of these wider aims was Federal Project Number One, which employed musicians, writers, artists and actors in large arts and literacy projects. The inclusion of the arts within a national programme shifted the status of art and artists in American society. Art took its place as a feature of national infrastructure and the work of being an artist took its place alongside the labour of any other citizen. Art and artists came to occupy a heroic position in the country, to the extent that Jackson Pollock, one of the artists supported by the FAP programme, could feature on the cover of Time magazine in 1940.

Federal Project Number One consisted of five different arts programmes: a Historical Records Survey, and separate projects for writers, theatre, music and art. The Federal Art Project (FAP), the largest of these, was led by Director Holger Cahill, a firm believer in the importance of art in everyday life rather than as a commodity of the wealthy. Cahill oversaw the production of an enormous body of more than 200,000 artworks, including murals, sculptures, paintings and drawings, all destined for public places such as schools, civic buildings, hospitals and parks.

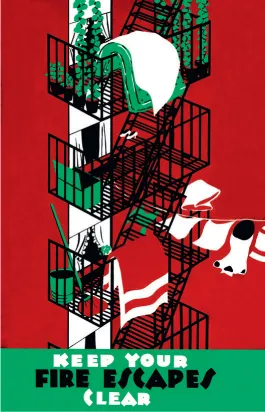

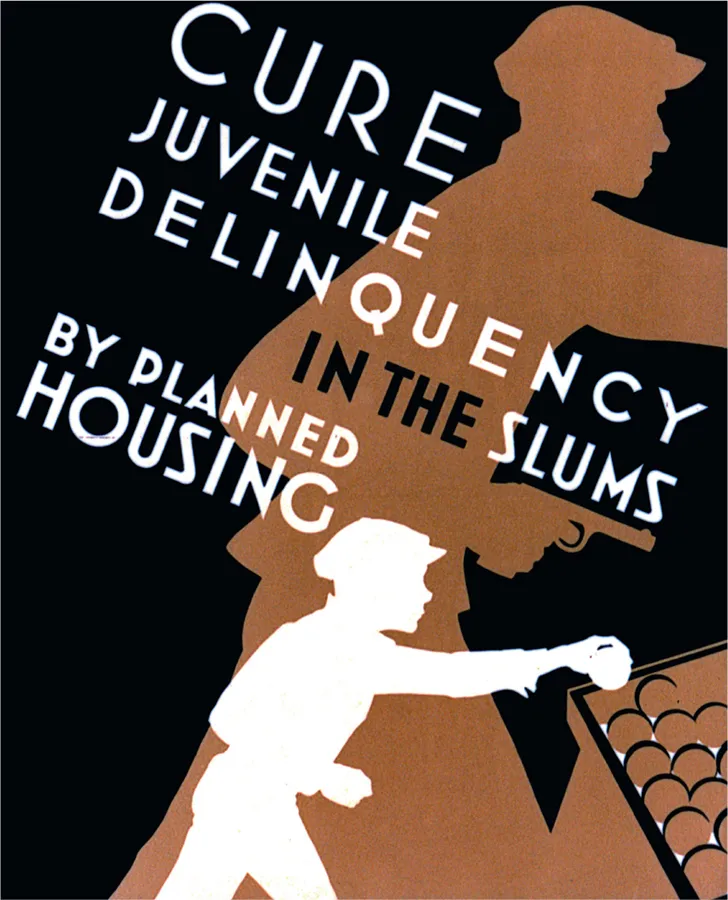

In addition to producing decorative works, artists working in the FAP produced hundreds of public information posters encouraging everything from literacy to health and safety at home. The poster project within the FAP not only provided work for graphic artists and printers, it also created a collaborative community that developed and enhanced the technical and artistic quality of poster design, such that it became accepted as a fine art medium in its own right. Finally, it was the means by which other programmes in the WPA were promoted and established in public awareness. Posters, then, were vital to the success of the New Deal as a whole.

The rhetoric on some of the WPA social policy posters bears a distinct similarity to posters produced under Soviet and Chinese communism, targeted as they are at the decision-making elite.

WPA: Books and Literacy Posters

(1936–1943)

Between 1936 and 1943 over 35,000 original poster designs were created by artists working for FDR’s New Deal Federal Art Project. They announced events and exhibitions, conveyed public health messages and promoted public programmes such as housing and literacy.

Posters produced by the Federal Art Project (FAP) were designed in response to requests from other public bodies and national and state programmes involved in the New Deal. By 1938, there were FAP poster divisions in at least eighteen states. The New York poster project alone, which employed around fifty artists, produced more than 300,000 prints from 11,240 designs. This remained the most influential and innovative studio, technically and artistically.

Richard Floethe, an established graphic artist and illustrator who had trained at the Bauhaus, was the dynamic leader of the New York project and responsible for the building of a highly collaborative and inventive studio. He was committed to a utilitarian view of art in society. Good visual thinking should be integrated into all aspects of society, and the designer should be equally at home in industrial design as in fine art.

Artist Anthony Velonis is credited with introducing methods of commercial mass production, notably silkscreen printing, which radically expanded the capacity of the poster projects. Silkscreening was cheap, and could be undertaken in the same studio as the design work, overseen by the design artists who could attend to the quality of the finished work. The technique, using flat plains of colour layered on top of each other, also created an underlying stylistic unity in the posters, despite the variety of styles and artists – many of them European emigrés who brought their stylistic signatures with them.

As well as schooling and remedial classes, the WPA expanded public library provision. In 1934, only two states provided public library access to their total population. Funding was provided on a state-wide basis and for individual library activities. In particular, libraries were introduced in rural areas, which had previously lacked any provision. A contemporary report from 1938 stated that 18,000 people were working in WPA library projects in thirty-eight states. In addition, 12,000 people were involved in book repair projects for school and public libraries in thirty-six states.

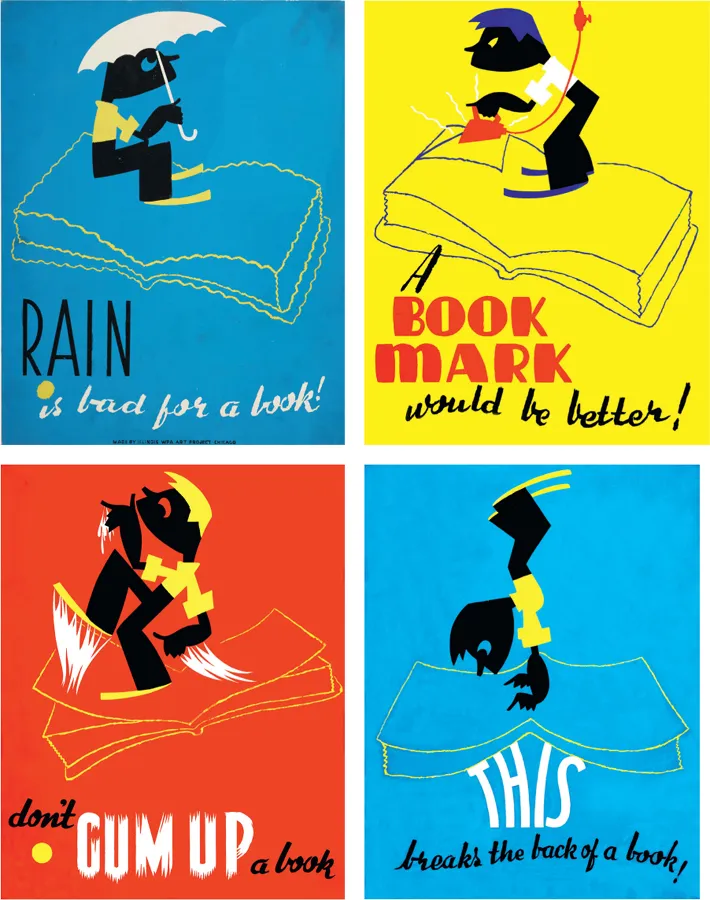

Posters were commissioned to promote reading and to advise appropriate use of this expanded library provision. The Illinois Statewide Library Project, for example, commissioned a series of posters from the Illinois Art Project (IAP) in Chicago to encourage reading by both adults and children. The IAP also produced a series of humorous posters to teach children that the books from the library should be cared for. Designed by artist Arlington Gregg, they showed how you shouldn’t treat a book, for example by letting rain get to it, or turning pages with sticky fingers.

Arlington Gregg’s fun posters aimed at book preservation.

Many great authors to read in March, but bizarrely Mark Twain is given his real name, Samuel Clemens. This may have something to do with Twain’s great novel Huckleberry Finn, which has been on and off approved library lists since it was published.

WPA: See America Posters

(1936–1943)

FDR’s New Deal was designed to nurture a sense of unity and community in an America brought low by the Great Depression. Posters promoting the country’s scenic beauty contributed to these nation-building aims by affirming a shared...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Introduction

- Early Wanted Posters (1651–1881)

- Early Recruitment Posters (1776–1795)

- Anti-Slavery Campaigns (1788–1865)

- The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1829)

- Balloon Trips (1839–1878)

- Emigration Posters (1839–1955)

- Circus Posters: Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite (1843)

- Vaccination Posters (1851–1999)

- Pictorial Wanted Posters (1865–1934)

- French Litho Posters (1881–1890)

- Columbia Bicycles (1886)

- Toulouse-Lautrec and Advertising (1890–1896)

- Imre Kiralfy’s Spectacles (1892)

- Edward Penfield: Harper’s Magazine (1893)

- US Magazine Posters (1893–1898)

- Buffalo Bill Posters (1893–1903)

- Alphonse Mucha: Sarah Bernhardt (1894)

- Barnum and Bailey Posters (1895–1899)

- Film: Lumière Brothers (1896)

- Belle Époque Advertising (1896–1905)

- Michelin Man (1898)

- Magicians’ Touring Shows (1900–1920)

- US College Posters (1900–1909)

- Illustrated Directory Posters (1905)

- Women’s Suffrage: UK (1907)

- Motor Racing Posters (1908–1935)

- Women’s Suffrage: America (1909)

- Anti-Women’s Suffrage (1910)

- World War I Recruitment: Kitchener (1914)

- World War I: Drink Campaigns (1915)

- Recognition Posters (1915–1942)

- World War I Recruitment: “Daddy, What did you do in the Great War?” (1915)

- Armenian Aid Posters (1915–1918)

- World War I: Winning US Public Opinion (1917–1918)

- World War I: German Propaganda (1914–1918)

- World War I Recruitment: Uncle Sam (1917)

- World War I: US Liberty Bonds (1917–1918)

- Temperance Posters (1920)

- Enhanced Colour Travel Posters (1920–1963)

- Art Deco Travel Posters (1922–1937)

- Lucky Strike Cigarettes (1928)

- The Cult of Stalin (1930s–1953)

- Coca-Cola Santa (1931–)

- Nazi Third Reich Posters (1932–1943)

- Transatlantic Liners (1935)

- 1 May Celebrations (1936–1977)

- WPA: Social Policy Posters (1936–1943)

- WPA: Books and Literacy Posters (1936–1943)

- WPA: See America Posters (1936–1943)

- Spanish Civil War Posters (1936)

- Pan American Clippers (1939–1942)

- Keep Calm and Carry On (1939)

- World War II: Boosting Morale (1939–1945)

- Careless Talk Costs Lives (1939)

- Dig For Victory (1939)

- Chesterfield Cigarettes (1940s–1960s)

- Appeal For Binoculars (1917 and 1942)

- VD Posters (1942–1946)

- Rosie the Riveter (1943)

- Tokio Kid Say… (1943–1945)

- Norman Rockwell: Four Freedoms (1943)

- Australian Road Safety Posters (1949–1954)

- Einstein (1951)

- Vietnam Propaganda Posters (1953–1963)

- Film: B-Film Thrillers (1957–1958)

- TWA Jet-Age Posters (1959–1965)

- Athena Posters (1964–1995)

- The Cult of Mao (1966–1976)

- Fillmore Hall, San Francisco (1966)

- Che Guevara (1967)

- Warhol: Marilyn (1967)

- Martin Luther King: I Am A Man (1968) 158

- Mexico Olympics (1968)

- Woodstock (1969)

- Missing Posters (1969–2005)

- Anti-Vietnam War Posters (1970)

- Contraception Posters (1970–1995)

- Keep Britain Tidy (1970s)

- Bullfighting Posters (1972) 172

- Anti-Smoking Posters (1975–2017)

- Film: Jaws (1975)

- Farrah: Red Swimsuit (1976)

- Seal Clubbing Protest (1977)

- Labour Isn’t Working (1978)

- Theatre: Cats (1981)

- Film: E.T. The Extra Terrestrial (1982)

- Nuclear Waste Trains (1983)

- Drink-driving Posters (1983–1996)

- Live Aid (1985)

- AIDS Posters (1986–1987)

- Drug Abuse Posters (1987–)

- PETA Posters (1990–2019)

- Banksy: Girl With Balloon (2002)

- Anti-Trident Nuclear Missile (2006–2016)

- Stonewall Campaign (2007)

- Obama: Hope (2008)

- Theatre: Hamlet (2010–2020)

- Theatre: Hamilton (2015)

- Moped Thieves (2017)

- Extinction Rebellion (2019)

- Index

- Acknowledgements

- Also in this series

- About the Author

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access 100 Posters That Changed The World by Colin T. Salter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.