![]()

SOUND

We do not hear the sound of the horse-drawn carriage crossing the Leeds Bridge, the Klan galloping in The Birth of a Nation, Cesare’s madness in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the distant traffic as Harold Lloyd climbs his building in Safety Last, the ocean the eponymous hero crosses in Napoleon, the pram bumping down the Odessa steps in Battleship Potemkin or Falconetti’s breathing in The Passion of Joan of Arc. The energy or tenderness of these images have a power to impress, but not as things in the real world do.

The otherworldliness of cinema started to decline after 1927 as the next great epoch in film history began. Movies across the world began to speak over the next eight years. At first, sound films were stagy because the equipment was cumbersome and audiences heard starchy conversations, people singing, doors slamming and dogs barking. Films largely moved indoors because filmmakers needed silence to record voices. Then something else happened: filmmakers discovered that sound could make their films more intimate by letting characters voice their thoughts. They used sound as a magnet to draw people into their film, into scenes and into emotional exchanges. Audiences started to feel that they could be with movie stars not only in their fantasies, but also in their ordinary lives.

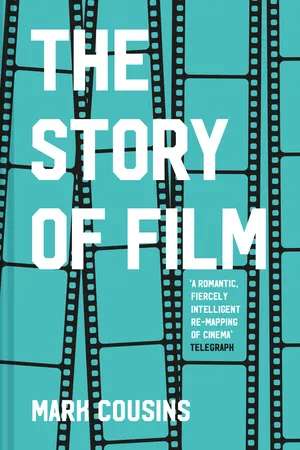

Sound was, “the discovery that halted cinema on its royal road”. Suddenly the image was not primary. However, it would be forty-five years before a mainstream movie would take the effect of sound as a philosophical subject in itself, in Francis Coppola’s The Conversation (USA, 1974), a film about a man’s obsession with what two people say to each other, which leads to his eventual breakdown.

80

Gene Hackman as sound recordist Harry Kaul in The Conversation. Director: Francis Ford Coppola. USA, 1974.

![]()

4

JAPANESE CLASSICISM AND HOLLYWOOD

ROMANCE (1928–45)

Cinema enters a golden age

Cinema started to sing in the years 1928–45. Five times as many people flocked to the movies each week as do now – they became an international obsession. Popular music and the tabloid press fostered escapism too, but cinema had more impact. One writer commented on how the “abundance, energy, transparency, community” of the entertainment films appealed to audiences because it was the opposite of “scarcity, exhaustion, dreariness, fragmentation” of their real lives.1 Surely, this is how entertainment works. It finds form for feelings that are missing. It is “what Utopia might feel like rather than how it would be organized.”2

This chapter is about cinema’s attempts to describe this utopian3 feeling. Countries such as Egypt, China, Brazil and Poland start, for the first time, to make significant films and stylistically, filmmakers learnt to use sound creatively. Japanese masters Ozu, Naruse and Mizoguchi, among others, tell stories in a rigorous way which partly qualifies them as film history’s classicists. The biggest formal shift in this period is that, after years of flattening and romanticizing its imagery, Western mainstream cinema begins to explore space in more visual depth. In the last chapter, each stylistic group was discussed separately, but this one navigates the period chronologically, crisscrossing the globe to examine cinematic events and landmarks.

81

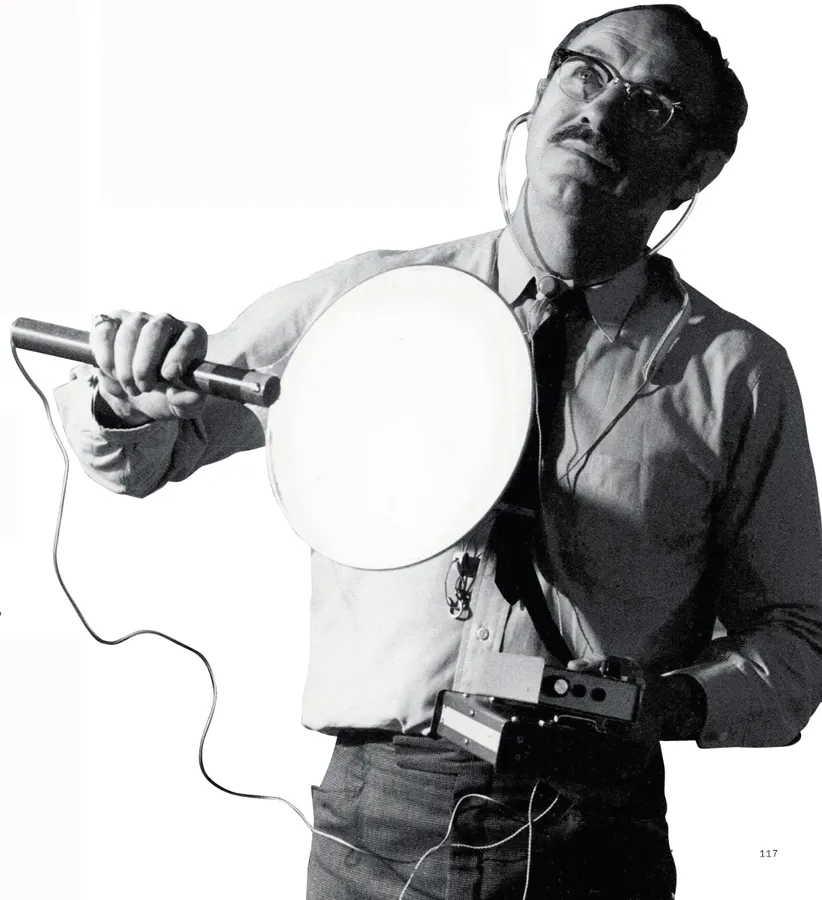

Choreographer Busby Berkeley’s interest in regimented movement and eroticism led him toward semi-abstract imagery such as this one, an overhead shot of twenty-five chorus girls playing violins. Gold Diggers of 1933. Director: Mervyn Leroy. USA, 1933.

THE CREATIVE USE OF SOUND IN AMERICA AND FRANCE

There had been previous attempts at sound cinema before The Jazz Singer’s release at the end of 1927, but this film was well-funded and widely released.4 It was successful and, as a result, American cinemas, followed by those of other countries, started to install speaker systems behind their screens; ten million more cinema tickets were sold in the US immediately after the introduction of this new technology. Many silent filmmakers, such as Chaplin, thought that the onset of sound destroyed the mystique of film and delayed using it for as long as possible. Some highly developed national film industries, including Japan’s, did not invest in sound technology until the mid- to late 1930s. From the filmmakers’ point of view, shooting sound was a whole new ball game. Real locations were now difficult to use because as soon as the director shouted “Action!”, someone nearby was bound to start digging a road or hammering metal which would interrupt filming. Directors and producers were forced to return to filming in “black box” studios, which were now called “sound stages”.

The image to the right (82) illustrates how problematic this new system was. The scene is a simple one, a couple talk on a park bench. They are placed on the far right of the frame and in front of them are three large wardrobe-shaped boxes. At the beginning of the sound period, cameras had to be housed in such boxes, or “blimps” as they were called, so that their whirring would not be picked up by the microphone. Each container is further muffled by large blankets and, behind the third of these, the “boom operator” sits on top of the leftmost camera. He holds a long pole, a “boom”, at the end of which the microphone records the actors’ dialogue. He moves this according to which actor is speaking and must keep it out of shot at all times. Surprisingly, an orchestra to his left performs as the actors speak. It was not until 1933 that music could be added separately to a film’s soundtrack after the editing had taken place. Until then, astonishingly, it had to be recorded simultaneously. Quite a pressing reason for not filming on real streets.

In the silent period, multi-camera shooting was used only for big action stunts which could not be easily repeated, so why were these three cameras used to cover this intimate park bench conversation? The answer again relates to sound recording problems. If this scene was first filmed in a wide shot followed by close-ups of the man and the woman, it would be very difficult to edit or match the sound from each shot together. The orchestra and dialogue had to pace one another to precise fractions of a second – if they failed to do this and the editor cut from a wide shot to a close-up, the sound would jar. The solution was to run three cameras, one filming the wide shot (in this case the centre camera) and further cameras photographing the actors’ close-ups (here one on the right and one on the left in front of the boom operator). The actors would then perform the whole scene in a continuous take to ensure that sound on each camera would match seamlessly.

82

This photograph, taken during the making of a Warner Bros. film, shows the coordination involved in early sound recording. Three large draped boxes house the cameras (below), a man holds a long boom over the actors’ heads (far right) and a small orchestra plays.

Actors’ performances were affected by this new technology. The director could no longer talk to them during a take, as was the norm in silent cinema, and in the first years of sound actors had to talk with unnatural precision to be recorded successfully by the crude sound recording technology. It was not until 1932 in America, and later in other countries, that directional microphones were introduced which could record specifics rather than picking up every sound. Notice, finally, that the couple on the bench are illuminated by just two big studio lights, one on each side of the trio of cameras. In late silent films, close-ups were lit separately and with great care to create attractive facial shadows and moody or romantic backgrounds. But here there is no chance of doing this, because the lighting stands for such set-ups would have to be behind or beside the actors, in the place of the bushes. They would then be clearly visible in the wide shot, which is filmed simultaneously with the close-ups.

Creative directors were immediately frustrated by these obstacles to their artistic freedom and the best devised ways of obviating them. In her 1929 film The Wild Party, Dorothy Arzner had a microphone attached to a kind of fishing rod so that it could follow the film’s star, Clara Bow, who wanted to move around the set more freely than the new technology allowed. The Russian director Rouben Mamoulian went to the West as a student of the great acting guru, Stanislavski. Hired by Paramount on the strength of his inventive theatrical productions, his first film, Applause (USA, 1929) pushed the creative boundaries of sound films. The film’s storyline was not innovative – an ageing stage entertainer sacrifices her career for her daughter – but some key scenes made the industry pay attention. One contrasts the convent’s hushed atmosphere, which has housed the daughter, with the hubbub of traffic and street sounds of bustling New York as she visits her mother. Mamoulian used sonic contrast to reflect the feelings of the disorientated daughter. In a later example, there is a more daring technical innovation. A wide shot, which encompasses most of the bedroom, shows the mother trying to calm her child’s frayed nerves in a night-time scene. The camera dollies into a two-shot, which frames the mother and child and remains there for a minute of dialogue, before moving into a closer two-shot, followed by two medium close-ups and then into a single close-up of the praying daughter as her mother sings a lullaby. Finally, the camera tracks out again and the father’s shadow falls across the scene.

Mamoulian’s sound crew told him the prayer and the lullaby could not be done simultaneously; we could hear one or the other or a combination of the two, but not both clearly. Mamoulian suggested that they use two microphones, one for each actress, run separate wires from them and then combine them in the printing process. The sound men said this would not work. Mamoulian was furious and stormed off the set. The studio boss, Adolph Zukor, ordered the technicians to try Mamoulian’s way, and it worked. A single scene in Applause proved simultaneous sound possible in cinema. New schema were opened up and directors now had to decide whether they wanted audiences to hear one thing or more and if other sounds should derive from the action within the image or from elsewhere. The idea of background noise, sonic landscape, threatening or warning sounds, were born in this advance.5

83

Maurice Chevalier’s actions are perfectly timed to music in Love Me Tonight. Director Rouben Mamoulin played the recorded score while the shot was being taken. USA, 1932.

84

Jeanette MacDonald bored on her balcony in an innovative early musical Love Me Tonight. Director: Rouben Mamoulian. USA, 1927.

Thre...